Male Ego Bulls**t: On Martial Arts Training, Violence, and Toxic Masculinity

By Jesse Goldberg

This past summer, I got to watch a friend of mine win her first sanctioned kickboxing title. I’ve been training in martial arts for twenty years now, and while we don’t train together much anymore I can say that this woman is one of the best training partners I’ve ever had.

By simple numbers, most of the people I’ve trained with as an adult have been men. I’ll say immediately that I don’t believe that this is because men have some kind of gene or brain composition that automatically makes us more interested in learning martial arts; there is a difference between the words influence and determine in the always too reductive “nature vs nurture” frame which should keep any thinking person away from essentializing gender. Rather, cultural and social factors impose from before an individual is even born – from the moment parents decide to “reveal” the sex of their child – the expected and acceptable interests of individuals based on an interpretation of their genitalia and chromosomes. There is an immense body of anecdotal and peer reviewed testimony on this, which I’ll defer to in moving back to my reflection.

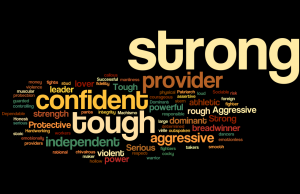

It is within this societal culture of gendering that I learned what it meant to be a boy, and then a man. It meant not ever crying, playing sports, being strong, wearing pants rather than skirts, being sexually attracted to women of a specific body type, being strong, horsing around, relying on myself and not accepting help from others, protecting woman who could not protect themselves (which I learned was all women), being strong, to view life as a series of competitions with winners and losers, not being afraid to use violence, and did I mention being strong? (Here’s a great poem that captures how I feel about “being strong.”) And a logical extension of being strong was to not show weakness or vulnerability, and to never let an attempt to challenge my strength go unmet.

It is within this societal culture of gendering that I learned what it meant to be a boy, and then a man. It meant not ever crying, playing sports, being strong, wearing pants rather than skirts, being sexually attracted to women of a specific body type, being strong, horsing around, relying on myself and not accepting help from others, protecting woman who could not protect themselves (which I learned was all women), being strong, to view life as a series of competitions with winners and losers, not being afraid to use violence, and did I mention being strong? (Here’s a great poem that captures how I feel about “being strong.”) And a logical extension of being strong was to not show weakness or vulnerability, and to never let an attempt to challenge my strength go unmet.

So it is with all of this cultural baggage that I walked into a particular moment at my friend’s bout this past summer. I was introduced to a friend of a friend who had just started training in Muay Thai. Upon first shaking hands, our mutual friend mentioned that I’ve been training in martial arts for so long, and this guy’s very first statement was, “Wow, so you’d definitely kick my ass.”

There’s so much to unpack there. The very first thought he uttered was not about the commitment it must take for someone to spend two decades training, or to offer his own experiences, but to size me up as an opponent. And it’s probably worth mentioning that there was some machismo backhandedness to his comment, given our very different bodies; I’m 5’7” and 140 lbs, and I’d put him at 6’4”, 240.

In any case, we got to talking and he asked me what styles I had trained in. When I told him, his first question was what advantages that would give me over someone training in Muay Thai – again, this was apparently a competition I didn’t volunteer to enter but had no hope of escaping. Fine. I asked him how Muay Thai was going. He said that he was enjoying it thus far but that he kept getting in trouble for hitting too hard during sparring. I explained that the purpose of sparring is not to actually “beat” your opponent, who isn’t really an opponent but a partner, but rather to push each other to learn about yourselves. In that vein, hitting hard actually winds up detracting from sparring as a learning experience for beginners (I have other thoughts on contact levels for advanced training, but that’s for another time).

Then came the most honest expression of the toxic masculinity bubbling below the surface of our interaction. The man said, “Yeah, but when someone hits me I just feel like I have to hit them back harder, you know?”

I did. “Well for a lot of men, especially guys who start training as adults, the most important lesson to learn has nothing to do with punching and kicking,” I told him, “but rather it is to get rid of that male ego bullshit that makes us think we have to hit harder than the other guy when he hits us.”

Male ego bullshit. In twenty years of training, those three words embody one of the single most important lessons martial arts has taught me, and a lesson I try to teach the men and boys in my life, be they friends, family, colleagues, or students (I am a teacher by vocation).

It’s something I see all the time in training first-time adult students, especially men, in karate. When they enter the sparring ring, technique goes out the window after the first time they’re hit and a one-track mindset of “punch that guy in the face!” takes over. I believe this is because as men we are taught to view our strength and toughness as the ultimate core of our personae. The societal norm which teaches us this is called toxic masculinity.

It’s something I see all the time in training first-time adult students, especially men, in karate. When they enter the sparring ring, technique goes out the window after the first time they’re hit and a one-track mindset of “punch that guy in the face!” takes over. I believe this is because as men we are taught to view our strength and toughness as the ultimate core of our personae. The societal norm which teaches us this is called toxic masculinity.

If we show weakness, if our physical dominance is challenged, it is a direct attack on who we are on an existential level. And because we are taught to outwardly assert our strength and toughness, especially when we perceive it to be challenged, these moments when the core of who we are is attacked result in us lashing out with violence at those around us.

Most fundamentally, this means that boys and men are socialized into feeling entitled to positions of dominance, and when those positions are threatened we are then licensed to use violence, which is the only tool we ever learn is acceptable (“boys will be boys” but “real men don’t cry” and definitely don’t seek mental health care), to “reclaim” that dominance we thought was ours. In the sparring ring, this manifests in poor technique and an increased risk of injury. In society writ large this results in the fact that in the U.S., over 95% of mass murders are committed by men, while mass murder victims are over 60% women and children. (Read this, this, this, this, this, and this.)

As a person whose body was declared male at birth and raised with traditional notions of gender, I too was socialized into toxic masculinity, but I also had the good fortune of being encouraged by my martial arts training to, from an early age, actively work against what I call male ego bullshit. While the martial arts are certainly not a utopian realm where hegemonic masculinity disappears – far from it, though that’s a topic for another essay – traditional training can encourage other ways of doing gender. This video is just one example of what I’d love to see more of in dojos and in life. It’s not perfect, but it’s a great start towards modeling different ways of embodying masculinity.

It is possible, and not at all weak, to teach boys that being a man has nothing to do with physical strength, hyper-individuality, or asserting dominance. I learned from getting punched in the face a lot that “hit harder” is not a good life strategy. Once I got over the idea that every time I got hit, it was a personal attack on me as a “man,” I took that with me into life outside the dojo. It is part of the reason why I’ve never been in a real fight. When macho posturing starts in the bar or on the basketball court, I can smile and back away from confrontation because my manhood is not at stake. When I’m confronted with something I did wrong in a relationship with a friend or lover, I can accept the critique and ask how I can help the person heal, rather than become defensive of my bruised ego. I’m certainly not “cured” or completely divested of the toxic masculinity of the culture in which I was raised and continue to live, but my martial arts training has given me the tools to let go of the ego built-up by it so that I can be more open to the world around me, rather than always trying to reach outward to tame or control it.

One of the things I think the most about as I talk with my partner about our future plans for raising a family is how to teach gender in a responsible way to children we are years away from being ready to conceive. And if chance gives us the opportunity to raise a human being whose body is declared male, I look forward to teaching this boy that men are not reducible to our assertions of dominance. I look forward to teaching him that men are strong, and weak – and that strong and weak don’t equal good and bad; wear pants, and skirts; play sports, and dance ballet; make love and have sex, or don’t, with women, with men, with trans people, with genderqueer people, or with multiple or no partners, though always with affirmative, enthusiastic consent from all those involved; work in science, and the arts, or stay at home and raise families; develop healthy self-reliance, and view others as potential collaborators rather than competitors; and that men can, and sometimes must, cry and ask for help. And I look forward to doing this even if he never in his life wants to throw a punch. He doesn’t have to get into a sparring ring to learn to let go of male ego bullshit. The first time a teacher, or a friend, or, just as likely, an aunt, uncle, or grandparent tells him to “man up” or to be a big man and not cry, I look forward to talking to him to help him recognize that those are the words of other people, and that those expectations do not have to define how he lives and feels his life. I’ll teach him to ask himself, “Is that how you feel, or is that how someone told you to feel?” It is the least I can do to help shape a safer world in which he and his siblings and friends can grow up.

Pingback: Where Can I Get Certified As A Personal Trainer