EMERGING FEMINISMS, “Wrong or Right, Black or White?”: The Convergence of Race, Gender, and Justice in Constructions of Catwoman

By Jazlyn Andrews

Have you ever felt so intrigued by a fictional character that you want to explore every facet of them until they practically jump off the page into reality? The fictional worlds that exist within TV, film, and books have always been a way for my family and I to get lost with one another, cognizant of the fact that our exploration of alternate worlds brought about new insight into our own. And when this world became at times too much, my older brother would join me on journeys to exciting new places. He was my childhood hero, but when he introduced me to the city of Gotham I was more interested in the villains. We travelled through Gotham’s underground to meet Selina Kyle, who transformed into Catwoman once darkness blanketed the city. She was the first representation of a mixed-race woman that I remember being introduced to, and I was taken aback by how intrigued I was by her. She wasn’t concerned with fitting within someone else’s fixed categories and was completely comfortable with the contradictions she embodied. Ever since then I’ve been fascinated by and in some ways infatuated with the character, interested in what responses to her contradictory characterizations reveal about how we understand the grey areas that exist in our world.

Catwoman’s sexuality, portrayals of her as mixed-race, and her villain-vigilante dichotomy, provide a contrasting yet familiar image to Bruce Wayne/Batman that is needed in order to cement him as both a purveyor of justice and an ideal performer of hegemonic white masculinity. Batman’s performance of hegemonic white masculinity is dependent upon portrayals of him as heterosexual, as someone who upholds racial boundaries through his sexual preferences, and as someone who works within established systems of justice—such as the Gotham City Police—to bring down individual villains rather than attempting to dismantle entire systems of oppression. Cementing Batman as an ideal performer of hegemonic white masculinity serves to construct a narrative about justice in which villains are individual bad guys unaffected by systems of power in Gotham, rather than having us focus on how those systems of power influence individual’s actions. In constructions of her racial identity, her sexuality, and her precarious position as both villain and vigilante, Catwoman has functioned to challenge, but ultimately reinforce definitions of justice in which everyone who deviates from performances of hegemonic white masculinity—all Others—are deemed villainous.

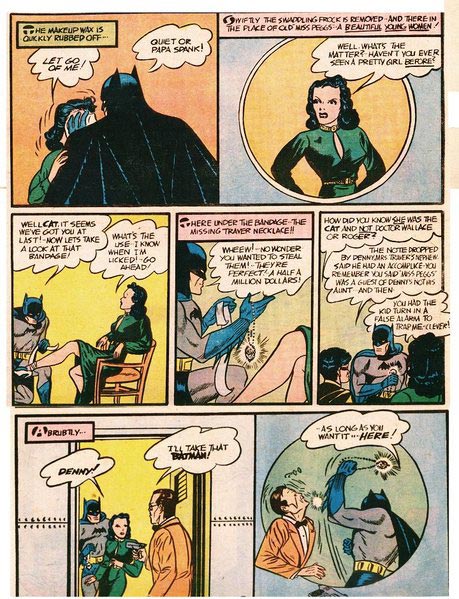

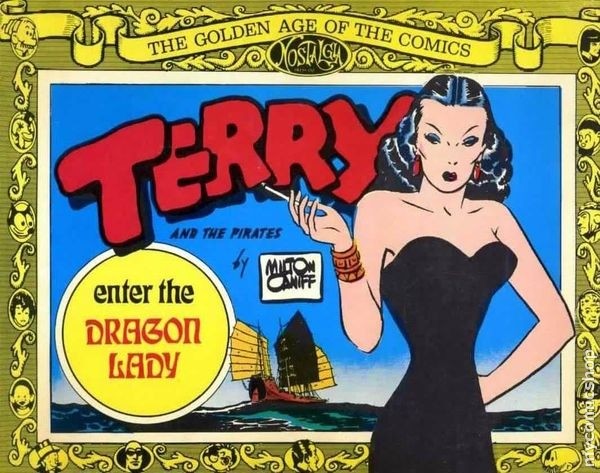

Created to dispel claims of homoeroticism, Catwoman’s overt sexual advances towards Batman fortifies his heterosexuality and reinforces racial boundaries by constructing women who are not white Americans as villainous. According to Deborah Whaley, author of Black Women in Sequence: Re-Inking Comics, Graphic Novels, and Anime, The Cat “was a European version of the Chinese, sexually volatile, and mistrustful femme fatale who used her sexuality to manipulate and entrap American heroes. Like Dragon Lady, the Cat exhibited the cunning, conniving, and potent gesticulating of a slithering, maneating animal.” Depictions of Catwoman (originally “The Cat”) as conniving and mistrustful serve to reinforce notions of hegemonic white femininity that are rooted in American nuclear-family values; any woman who lives outside the bounds of whiteness and/or who desires anything other than to serve others above herself is mistrustful. The villainization of The Cat reinforces a narrative in which white women who deviate from hegemonic white femininity are linked to Women of Color, who are already characterized as always mistrustful. Batman relies upon these depictions of a conniving Catwoman to act as a backdrop against which his justice situated within institutions that privilege whiteness can be defined. While Catwoman is able to tempt Batman with romantic and sexual advances, his dissonant feelings toward her in conjunction with his lack of superpowers allow readers to align themselves with him, and therefore with his performance of white masculinity. Catwoman’s character evolved to include portrayals of her as a Woman of Color, situating her within the villain-vigilante dichotomy and solidified her function as a boundary-maker of racial and sexual boundaries.

When Eartha Kitt replaced Julie Newmar as the femme fatale on Batman, the dynamic between Catwoman and Batman changed from one of romantic temptation to one of crime, reinforcing boundaries of hegemonic white masculinity that excluded interracial relationships. In the episode “Catwoman’s Dressed to Kill,” Kitt’s Catwoman kidnaps Batman’s white collaborator, Batgirl, and forces Batman to derail his previous plans in order to save her. This episode not only reinforces Catwoman as villainous but also connects villainy to Otherness as the audience is urged to associate Batgirl with Batman, and therefore with definitions of justice centered on upholding strict racial boundaries. Furthermore, the fact that Batman must fend off Catwoman in order to save Batgirl functions to reaffirm his connection to whiteness in opposition to Catwoman’s Blackness, all the while implying that the bond between two white characters is too strong to succumb to attempts to derail it. The implications of such a narrative are that those who build interracial relationships are deviant and that Black women are the catalysts for blurring that color line. This situates Black women as the manipulative agents in the context of interracial relationships and cements white men as the victims, freeing them from whatever accountability they have in the situation and allowing them to remain the ideal vessels of justice, even when they have transgressed the color line.

The relationship between sexuality, race, and justice is further complicated by portrayals of Selina Kyle as mixed-race that fracture the master-slave dialectic Batman relies upon to reinforce his constructions of vigilantism. Hegel’s master-slave dialectic claims that one must come in contact with another subject in order to assert one’s own individuality and freedom over the subject they have come in contact with. Since both subjects desire to affirm themselves, there is a drive to place oneself over the other, proving that they don’t rely upon each other to see their own reflection. Since they do in fact need to preserve their relationship in order to recognize their own selves, the victor of the confrontation—the subject—must perpetually assert themselves as in opposition to and above an abject Other. This creates a power dynamic in which the subject must construct the abject Other as a deviation from whatever norm the subject is attempting to construct. In order to justify their precarious status as subject, the victor of the confrontation must construct an aspect of the Other’s identity—such as race and gender—as deviant in order to justify their position over the Other. The villain-vigilante dichotomy Catwoman is situated within cannot be removed from her identity, as her gender and race are used as justifications for her to be constructed as villainous in opposition to Batman. This construction of justice creates a good/bad dichotomy in which the white masculine subject is perpetually “good” in opposition to the “bad” abject Other.

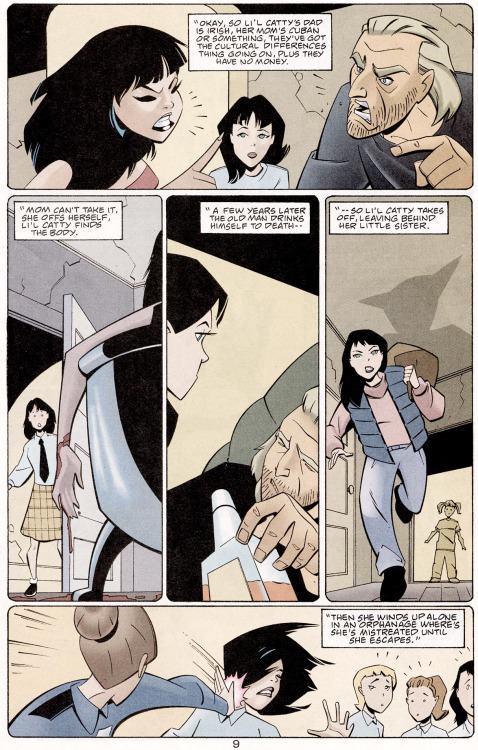

This construction of justice is complicated by depictions of Catwoman as mixed-race that function to provide a context within which Batman can continually reassert his status as subject in opposition to Catwoman’s abject Other. Despite fan speculation on Catwoman’s race, it is written in “Catwoman #89,” “Li’l Catty’s dad is Irish, her mom’s Cuban or something. They’ve got the cultural differences thing going on, plus they have no money.” Catwoman’s ability to fracture Hegel’s master-slave dialectic through her identity makes her one of Batman’s greatest foes as he is forced to challenge the good-bad moral binary he tends to operate within. In order for Batman to exist as a white masculine vigilante, he relies upon the construction of Catwoman as in opposition to and as inferior to him. Catwoman’s similarities to Batman—her origin rooted in the tragic loss of her parents and her animalistic transformation—challenge his understanding of himself. However, each time he rejects Catwoman’s attempts to lure him from—not only his definitions of justice, but also his boundaries of whiteness—he ruptures that reflection, thereby reinscribing his loyalty to constructions of justice woven into acceptable white masculinity. Though her identities grant her the freedom from the same confines Batman operates within, it is also reason for her to be constructed within a villain-vigilante dichotomy that serves to reinforce boundaries of justice that Batman represents.

The freedom with which Catwoman acts threatens to dismantle the structures that Batman relies upon to validate his performance of hegemonic white masculinity and justice. Whereas Batman takes cues from the Police Commissioner Gordon to determine how best to fight crime, Catwoman relies upon collaborating with others, often times villains (such as Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy), to achieve her goals. In their focus on collaborating with other women at the expense of men, the women Catwoman collaborates with offer performances of alternative femininity that reinforce Batman’s role as the upholder of acceptable white masculinity. The fact that they are villains only perpetuates the notion that their gender performances are not only alternative, but also deviant. Particularly when Catwoman is collaborating with women, she asserts that she does not rely upon Batman for validation of her sense of self. As Shannon Austin explores in “Batman’s Female Foes: The Gender Wars in Gotham City,” the villainous women of Gotham city subvert expectations that they need to prove themselves worthy in the eyes of the their male peers by collaborating with each other, and by doing so are constructed as conniving. The construction of Catwoman as villainous when she collaborates with characters other than Batman perpetuates a construction of justice dependent on performing the same hegemonic white masculinity that Batman does. The association between justice and performances of hegemonic white masculinity is not constrained to Gotham, but expands beyond the page or screen to inform and be informed by our society’s conceptions of justice.

For over seven decades Catwoman has gone through myriad metamorphoses, cycling through various backstories, and depicted by a wide range of women on the small and silver screens, but one thing remains constant: her function as a character against which Batman can justify and assert his performance of justice reliant on hegemonic white masculinity. Characterizations of Catwoman that tie her deviancy to her performances of femininity and race spill over from the world of DC comics to our version of reality, and have tangible consequences for real people. All we have to do to explore the relationship between hegemonic white masculinity and definitions of justice is look to news stories that uphold the vigilantism of white police by depicting unarmed People of Color as always already villainous.

Our constructions of heroes and their foes do not exist within a vacuum of some writer’s imagination, but are reflective of the ways in which we construct binaries of right and wrong, and who is allowed to be on either side of that line. Catwoman has held my attention since I was a child, and I expect will continue to intrigue me for years to come, but I cannot let my fascination with her draw my attention away from the implications that constructions of her have on our society’s understanding of race, gender, and justice. Nor can I ignore the ways in which our constructions of identity as it relates to justice inform portrayals of her and how I understand them. We must take an active role in media consumption, reflecting upon what we see, hear, and read through a critical lens that takes into account the implications of our creations on our constructions of society. We must recognize the power we have as consumers to help shape the creations we are drawn to rather than to blindly devour whatever producers push our way. And we must, as creators of media, go beyond representing diverse identity performances to interrogate the meaning of those representations. As we allow ourselves to get lost in other realities, our discoveries must remain rooted in how our journeys to far off lands are truly an exploration of the world around us.

Jazlyn is in her final year at Colorado College where she is finishing up a major in Feminist and Gender Studies and a minor in Race, Ethnicity, and Migration Studies. Her research for this paper was sparked by taking a Speculative Science Fiction class last year and will be continued for her thesis. She has no idea what the future holds but is passionate about feminist publishing and hopes to continue her education through Critical Media Studies.

Jazlyn is in her final year at Colorado College where she is finishing up a major in Feminist and Gender Studies and a minor in Race, Ethnicity, and Migration Studies. Her research for this paper was sparked by taking a Speculative Science Fiction class last year and will be continued for her thesis. She has no idea what the future holds but is passionate about feminist publishing and hopes to continue her education through Critical Media Studies.

0 comments