Generations of white women’s violence stop here: On watching the Amy Cooper video with my 5-year-old white daughter

By Annie Menzel

For white people working to align ourselves with justice, it makes sense to want to distance ourselves from Amy Cooper, the “Central Park Karen.” Amy Cooper deliberately lied to police, accusing Black birder Christian Cooper of threatening her life when Mr. Cooper asked her to respect the park’s dog-leashing rules and began to document her refusal. As Nylah Burton argues, it is important that progressive whites acknowledge our political kinship with Amy Cooper: that she is solidly liberal, not a Trump-supporting reactionary. But white parents—and white mothers in particular—must dive even deeper into this kin relation, and confront the lineages that we share with Cooper—and with BBQ Becky, Permit Patty, Pool Patrol Paula, and the countless other manifestations of the white feminine face of police terror.

Most white parents that I know are anguished and distressed at the pervasiveness of police and police-sanctioned murders of Black people. Just in recent weeks: Breonna Taylor. Tony McDade. Ahmaud Arbery. George Floyd. Rayshard Brooks. 18-year-old Tony Robinson, in my town of Madison, Wisconsin (occupied Ho-Chunk land), back in 2015, in the next neighborhood over from ours. Christian Cooper’s name was not added to this litany—but as Apryl Williams has pointed out, Amy Cooper’s call might well have resulted in his murder.

Growing numbers of white parents in my networks have also been participating in protests, donating to abolitionist groups, and following with amazement the way that organizations working for Black liberation—like Freedom Inc. and Urban Triage here in Madison—have made defunding and even dismantling the police real options.

How can we bring our children along, and support within them the capacity and desire for a world without police or prisons? The folks at Embrace Race (and many other organizations and individuals) have challenged us as white parents to talk openly with our kids about racism, the ongoing legacies of slavery, and the police murders of Black people. Powerful resources exist to get us started; recent events on this theme include this panel with Dr. Kira Banks of Raising Equity and Dr. Beverly Tatum, and this event featuring Ibram X. Kendi and Derecka Purnell.

Amy Coopers and Derek Chauvins don’t happen all at once or without discernible cause. There is much to say about directly murderous white masculinity and police violence. But as the white mother of a white daughter, I am homing in here on Amy Cooper’s deceitful phone call to the police, an everyday act of anti-Black racism remarkable only for being so explicit in its illustration of a long history of white women’s murderous bad faith.

In They Were Her Property, historian Stephanie Jones-Rogers writes that plantations were, in addition to bloody machines for capital, “a school,” where slaveowners’ white daughters daily absorbed from birth lessons of violability of Black life and their own entitlement to control Black people’s bodies. These lessons in dehumanization were necessary preparation for their own adult slaveownership. After emancipation, the lessons of anti-Blackness persisted through multifarious forms of Black criminalization and lynch law; white girls across class lines were socialized into the knowledge that their own transgressions could be disappeared by what anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells called “the threadbare lie” of Black men’s sexual threat. This lie, in its threadbareness and horrific efficacy, has remained on the white supremacy syllabus ever since. 14-year-old Emmett Till was brutally murdered after Carolyn Bryant Donham lied—an atrocity that, as Michael Harriot notes, echoes in Amy Cooper’s call. Angela Davis’ classic analysis of the “myth of the Black rapist” remains hideously current. Our contemporary society, still so profoundly structured by slavery’s ongoing legacies, patriarchy, and racial capitalism, continues to educate white girls into this lie, body and soul.

While not always explicitly sexual, the lie of Black threat is bound to the particular brew of domination and subjugation that underpins normative white femininity: a quick visual survey of the BBQ Beckys, Newport Nancys, and Amy Coopers suggests that while they span the class spectrum from working-class to elite (though skewing toward privilege), they are all conventionally feminine-presenting, apparently typically-abled, cisgender women. And, as in the era that Jones-Rogers charts, white women’s exercise of deadly force continues to be about property and control of Black people’s bodies—whether literally gatekeeping private residences, or a proprietary relation to public spaces of parks and pools.

This calls for confrontations with what feminist philosopher Alexis Shotwell calls white colonizers’ “bad kin.” Shotwell figures as bad kin among others, such as the culturally appropriative white friend and the paradigmatic racist uncle (whom she urges us to “call in” rather than disavowing) as well as explicitly white supremacist groups (whom she encourages white people to “claim back” by taking the frontline of direct opposition). Shotwell suggests that such confrontations are a necessary component of white people’s joining in struggles for decolonization, anti-racism, and collective liberation.

Just as crucial are confrontations with that bad kin within ourselves and our ancestral lines, which we otherwise continue to pass down regardless of good intentions. Visionary Zen priest, teacher, and author Reverend angel Kyodo williams argues that, in order to inhabit radical possibilities of future liberation and life, whites must reckon with the violent pasts and ancestors that live within the self. As Rev. angel said at a recent panel: “in that practice of stillness…you can differentiate what is endemic to you and what you have inherited…history becomes that reference point…I thought that was me and it turns out that that has happened again and again and again…there was Amy Cooper that decade, that decade, and that decade…these are not just individual choices but…it takes individual responsibility and accountability to shift that pattern…but you have to be invested, you have to want to pull that illness out of your body like it’s killing you, because it is.”

I just learned a few months back, as my mom went through old family papers, that my great-great grandmother, Carrie Alice Miller Peairs, photographed here with her daughters, was a teacher at a series of Bureau of Indian Affairs schools on Puyallup, Yakama, and Hopi reservations. I rage and mourn for those children, their kin and communities. I wonder how I might even begin to make reparation for my ancestors’ harms. And I also wonder what Carrie had to lay waste to, to cauterize within herself, in order to participate in these atrocities, as well as what she herself witnessed or bore, how she came to embody her own inheritance of white settler violence. I am haunted by the eyes of her daughters, my great-grandmother Gladys and her sister Edna. What did they witness? How did they learn not to see the blood that suffused their womanhood, their place in the family and nation? Did they also glimpse, and turn away from, other ways of being and relating among the peoples that their mother was charged to “civilize?”

What do I carry of those colonial horrors? How are they tied to anti-Blackness? And to cycles of harm borne as well as inflicted by these white settler bloodlines, in which addiction and abuse have been endemic? During my tween and teen years in segregated College Station, Texas, I never learned about the Tonkawa people whose land we occupied; I never learned about the nine lynchings that took place in Brazos County. In this town permeated with rape culture, I also never learned to value my own body, to say no, about consent or pleasure, or to breathe into my own inherent dignity. This is not in any way to minimize the far greater vulnerability of Black and Indigenous women and girls, and queer and trans folks to all forms of violence, including sexual violence. Yet, I feel the deep links between my socialization and experiences—from which the police never protected me—and the unbidden surge of my own inner Karen (or Carrie) when I feel thwarted in daily life, powerlessness and rage turned to an impulse to debase and punish others: customer service representatives, political antagonists, friends, family members, my own daughter.

Abolitionist and transformative justice visionaries like Mariame Kaba and Mia Mingus offer a way of thinking about cycles of violence that turns away from punishment and looks to transform the conditions from which they arise. As Kaba, drawing on Danielle Sered, says, “no one enters violence for the first time by committing it. Meaning that something happened to you that led to that other form of violence of you either lashing out, using violence, because that’s how you learned how to be whatever.” Along with making clear the absolute necessity of supporting local and national organizing against police and prisons, this framework urges me to encounter my ancestors, and the ways they live inside me still, with an accountability framework that demands reparation for harm—yet refuses to reject harmers as monsters, as not-me. Mingus writes, “This does not excuse people’s harmful behavior or mean that a person who has caused harm or been violent doesn’t need to be accountable for their actions, but it does mean that we need to understand the context in which harm and violence happen.”

Guided by these principles, our family and close community strive to cultivate in my daughter an inner and outer ecology inhospitable to Karen (and the larval forms of Kylie and Becky): a sense of inherent value in self and other humans and the more-than-human world; an understanding of consent and pleasure in age-appropriate ways; deep community that involves a variety of trusted adults; a preschool and kindergarten that refuses the criminalization of Black children, Latinx children, and other children of color; frank discussions about ongoing histories of racism and colonization and the inherent violence of police. It is also crucial to accompany her through confrontations with all of our bad kin, in Shotwell’s sense, from Carrie Peairs to Amy Cooper. It is utterly unjust that the video of the latter is, for my daughter and me, an opportunity to attempt these confrontations in bodily safety, while Black folks continue to face the mortal threat Cooper invokes. This unjust insulation charges us to watch and reflect on it in the service of both inward and outward action. Dr. Jennifer Harvey offers a thoughtful reflection on talking about the video with her white 9- and 11-year-olds, and speculates about how it might go with a younger child. I offer our experience as an imperfect example of how it actually went with a 5-year-old white girl.

Me: I want to talk about something that happened a couple of days ago, when a white woman lied and tried to hurt a Black man.

She: (not super interested) Ok.

Me: I am going to show you a video of it.

She: (now extremely interested, because a screen is involved) OK!

Me: OK. A white woman named Amy was walking her cute dog in the woods that were part of a special part of a park where lots of birds live. There were signs saying that dogs had to be on a leash. Why do you think that might be a good rule for these woods?

She: Dogs might chase the birds.

Me: Yes! But guess what, Amy took her dog off the leash. A Black man, Christian, was there to watch the birds, and he saw Amy’s dog. He said something like “ma’am, please put your dog back on its leash.” But she didn’t want to put the dog on its leash. Let’s watch the video to see what she did.

(We play the video through the part where she calls the police and reports an “African American man threatening [her]”)

Me: Is she telling the truth? Is Christian threatening her life?

She: No. She is hurting her dog!

Me: She is lying and she is also hurting her dog. She isn’t in control of herself, is she?

We have talked about how the police were invented a long time ago by white people to control Black people who they had kidnapped and forced to work as slaves, and protect rich white people’s stolen land and their stuff. And how police still kill Black people and Indigenous people and protect white people’s stuff. And they don’t make white people safe either. Remember how we talked about how police just killed a Black man named George Floyd in Minneapolis, where your friend A. lives. Black leaders here and all over are trying to make it so that there aren’t police anymore, and we want that too–that’s why we are going to protests right now.

From old times until now, white women sometimes lie and say that a Black person threatened them when they do something wrong or don’t want to follow the rules, because usually the police and other white people will believe them and they won’t get in trouble. That’s what Amy did. And she knew that if the police came, they might hurt or even kill Christian. But she did it anyway.

What do you think Amy could have done instead?

She: She could have said “OK, I’ll put my dog on his leash and take him to a dog park.”

Me: That could have been a good response. How do you think Christian might have felt when Amy called the police?

She: He might have been scared.

Me: Let’s watch Christian talking about what happened.

We watch this short video of Christian Cooper saying that he refused “to participate in [his] own dehumanization.” She didn’t offer any comments, but seemed to absorb the conversation.

As I watch the videos by myself, again, there are other questions I wish I’d asked, other ways that I might have better gone about it. In particular, I’d like to ask, what do you notice about Amy’s voice? The register changes from entitled threat to panicked fear as she makes the call—mock-fear, surely, but also reflecting the embodied, physiological experience of going, in Mr. Cooper’s words, to “a very dark place,” channeling centuries of a white femininity—as Sarah Bellamy powerfully observes—predicated on anti-Black violence.

At the same time, I wish that I had left more space open for my daughter’s own reflections. When our dialogue came up in conversation with other adults a week or so later, she denied any memory of the video. So, we watched it again, with fewer but similar prompts, and similar observations emerged. Was it in part because of my own intensity, my own white womanly desires for goodness, that the video actually didn’t stick, or that she wanted to distance herself from the experience? Was it discomfort speaking with adults that she didn’t know well? I wonder if, had I left her more space, she would have had more room to claim the discussion as her own. There was no doubt both more and less that I could have said.

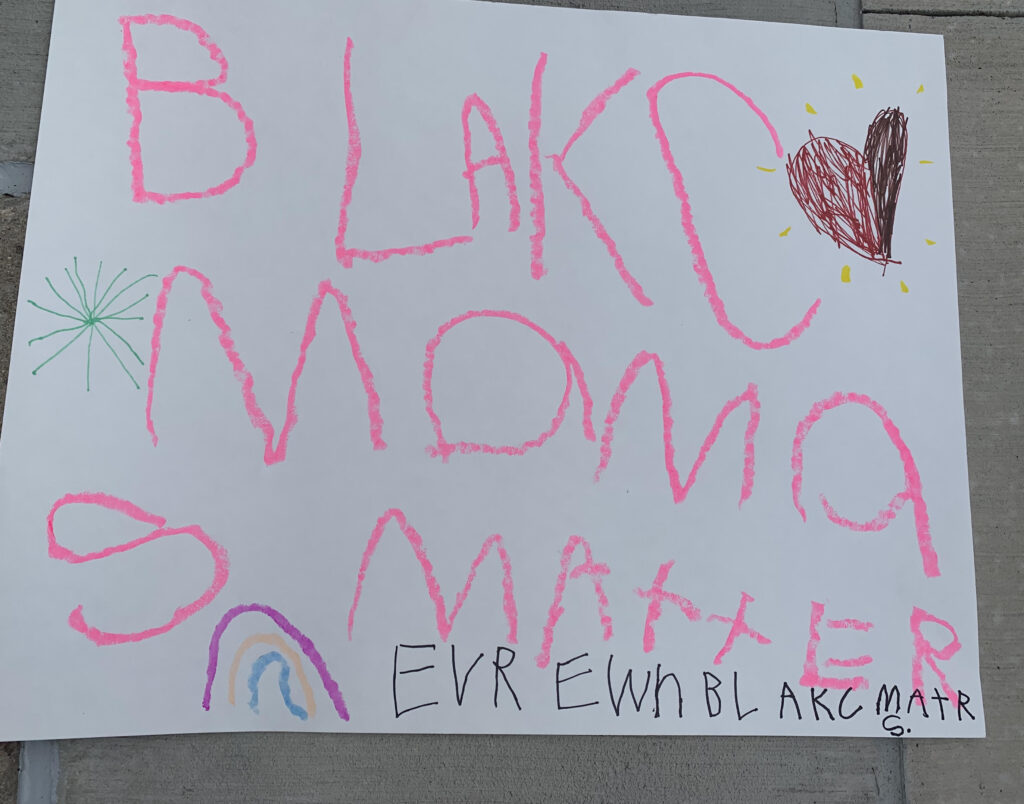

In our varying capacities to be out in the streets, it is key that we bring our kids along into the emergence of new and more liberatory ways of being. This could mean being present with them at protests and celebrations, including them in making the signs, sharing with them videos of our friends and comrades and movement leaders, and including them early and often in conversations about alternatives to calling the police. Recently, organizers from Madison’s Freedom Inc and Urban Triage led an hours-long shutdown of a major intersection. Part of the action was their choreographing of white protestors to form a perimeter around Black protestors and protestors of color, as an embodied practice of what our relationship to the police should be: protecting our Black comrades and comrades of color from them, not calling them for a shallow security that binds us to domination. Though my daughter wasn’t there that day, some other dear kids in our life were, and I was able to share my experience with her later. But if we don’t also explicitly face the poison in our cultural and family lineages, in tandem with acts of public solidarity, we might nevertheless find ourselves raising tomorrow’s Amy Coopers. And there is no reason to trust that the police will not shoot next time a white woman cries wolf.

What would accountability look like for Amy Cooper? I am not sure. It may be that losing her job and her dog could be part of a just response. But these consequences alone, accompanied as they were with self-righteous disavowals from her employer and other white people, will transform nothing. And proposed new laws categorizing Amy Cooper-type calls as hate crimes, even as they seem to promise a poetic reversal of racialized criminality and may make some white women think twice, will also give the police more power. The danger is, as Dean Spade has argued about anti-LGBTQ hate crimes, that they will inevitably turn this power against communities of color, queer and trans people, poor people, and people with disabilities. And it will do nothing to dissolve white femininity’s reflexive anti-Black “dark place.” Police power helps to maintain the toxic atmosphere of anti-Blackness that impacts Black women’s birth outcomes and obstructs reproductive justice. And police power is also instrumental in maintaining the ongoing system of colonial violence that my ancestors directly contributed to, which exposes 4 in 5 Indigenous women to violence and to murder rates over 10 times the national average. Rather than turning to hate crime laws, let us do away with the police altogether instead.

It is incredible the way that youth and veteran Black organizers are together realizing historic moves toward precisely this dismantling of our national police state. Let those of us who are white parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and cousins keep actively supporting these transformations with our bodies and resources. As part of this work, and in honor of our children’s potential for a humanity beyond white supremacist hierarchies, let us free ourselves from the inherited forms of white femininity—and masculinity—that keep us bound to the police, and to the racial capitalist, anti-Black, colonial, patriarchal order that they serve and protect.

With gratitude to Lisa Beard, Gail Konop, and Monica Casper for feedback on earlier versions, and to Rev. angel Kyodo williams for use of the quote.

Annie Menzel is a political theorist and former midwife whose work focuses on understanding how white supremacy, colonization, and gender-based oppression shape human reproductive life, health, and care—as well as theorizations and praxes of reproductive justice and freedom. She is completing revisions on her first book, The Political Life of Black Infant Mortality, under contract with the University of California Press, and is also at work on a second book project, Birthing Paradox: Race, Colonization, and Radicalism in US Midwifery, which seeks to understand the contradictory politics and practices of the homebirth midwifery movement since 1970. She has work published or forthcoming in the Du Bois Review, Contemporary Political Theory, Political Research Quarterly, Political Theory, Signs, and The Boston Review.

0 comments