My Education in Racism

By PK Read

I was eight the first time I took conscious note of a racial epithet. The year was 1970, the speaker was a friend of my stepfather’s, where he talked about an African-American man he encountered earlier that day. Only he didn’t call him that. He smirked and called him something else – Negro – illiciting a frown from my mother.

This moment made a few unexpected truths clear to me, ones I would only be able to unpick years later. The word he had used before must have been something bad, bad enough that my mother—no slouch when it came to swearing— knew it, disapproved, and never used it herself. Her reaction, a quick frown, a glance in my direction, a corrective look at the speaker, taught me the word was shameful or unpleasant. The wry correction to the more familiar Negro, which at the time was still used widely on television, told me that this parental friend thought he was only saying what everyone else did, just not on television. Most importantly, he used the other word as if the person was bad because of it – because of his skin color.

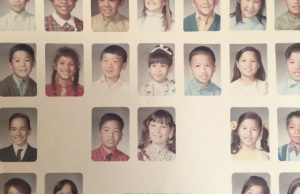

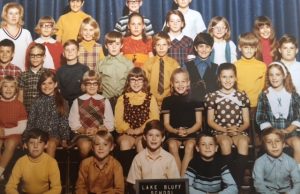

I had just moved from San Francisco to the suburbs of Milwaukee, part of the fallout of my parents’ divorce and my mother’s new marriage to a Wisconsin native. If the photo of my 1969 second grade class in San Francisco shows a potpourri of races—Japanese and Chinese-Americans, several African-American kids, a smattering of white faces and me, snaggle-toothed and still a tow-headed blond—then my new school in the Midwest was so uniformly Caucasian that after my first day, I asked my mother where all the other kids were.

“Other kids? There are hundreds of kids at your school.”

“Yeah, but they’re all the same kind. Where are all the other ones?”

I see now that, as a white middle-class kid, I had the privilege of being ignorant of race. At the same time, I know that my mother and father tried not to perpetuate the racism in which they had been steeped. Seeing your own privilege is like trying to look at the back of your own head—you know it’s there, but you need some kind of mirror to actually take a look at it for yourself.

No one mentioned race before we moved to the Midwest. According to my grandmother, this was because my late mother was determined not to pass along her own racist inheritance. In retrospect, more vigilance would have been required. We don’t avoid infection by simply not talking about the disease. We need to expose it to the air, show it for the poison that it is. What I lacked in racist training before arriving in an all-white suburb, I quickly made up for over the following four years. At school I learned a whole set of new words that didn’t just apply to race but to ethnicity, political beliefs, other religions, and other nationalities. I heard anti-Semetic jokes, anti-Polish jokes, anti-German jokes, anti-Asian jokes, anti-Native-American jokes, homophobic insinuations. I had to ask my stepfather why Mike with the Italian last name always blushed and got angry when other kids asked him ‘how’d your day go?’ at the school lockers.

Bigotry isn’t born. It’s something happens over and over, a wall of identity created by defining ourselves against what we aren’t, and making that Other inferior so we can feel stronger. It happens every single time we parrot a stereotype we know only by rote. At a summer street fair, a large-scale brawl broke out and we fled. My stepfather caught up with us a minute later, breathless. “I found some cops and told them there was a big fight, and they didn’t move,” he explained, catching his breath. Then he grinned. “So I said a bunch of spics and spades were mixing it up. That got their attention.” This is how we teach, and this is how we learn. It’s not the big stuff, it’s the small moments over each day, week, month, building stones for a life.

I took a long road trip with my father in 1972, Wisconsin to Maine and back to California. One of our passengers was a young Mi’kmaq woman heading home from working with the American Indian Movement on the West Coast with a profound dislike of white people. If I wasn’t directly responsible for oppression of Native Americans, then my pioneer ancestors were. True enough: My family had owned a large wheat farm in eastern Washington State, land granted cheap in return for settlement. What could I do about it, generations later? Not succumb to simplistic stereotypes about Native Americans. Not tout oppression as heroism. I would never have called this young woman a friend, there was too much antipathy on her side, but regardless, what she said stuck with me.

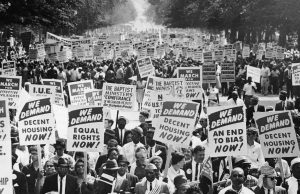

The Sixties and early Seventies were a time of radical upheaval. Anger at the status quo outweighed the benefits of keeping calm and carrying on. It was a time when no one could pretend blithe ignorance of the fact that some folks had it better than others—and it was when a lot of those who had it better were afraid of losing what they had. Sound familiar? Well, it’s that time of the societal clock again. In the 1980s, my two best friends and saviors were a Latina woman and her black boyfriend. Even though in we lived in the progressive city of San Francisco, we still got looks everywhere we went. My girl friend forgot her driver’s license when we went to the pre-ATM bank; one of the clerks ID’d her as “that chick who walks around with the white chick and the black guy” and approved cash withdrawal. That’s how unusual our little grouping was. On more than one occasion, her boyfriend was late in meeting us because he’d been stopped by police checking whether he’d stolen his own sportscar. Cops stopped us when we were walking and asked us (the women) whether “we were okay” with a glance at our friend. Yes, we were okay. These days, there is no plausible excuse for pretending ignorance for the inequality and inequities of treatment. The only question is, what are you going to do about it?

On a recent rare visit, I was walking south of Market in San Francisco,, among a multitude of people on the sidewalks, mostly young, very diverse. Thirty years after I moved away, I wouldn’t have recognized this glossy corporatized area as the gritty warehouse section of old. There were two young civil rights activists of color working the front of a Whole Foods store (!) on Fourth, passing out leaflets, repeating their slogans about fighting white privilege, stopping oppression. They passed out their leaflets to any hip young thing that walked out of the slick Whole Foods, as long as that hip thing was of color, too. I tried to make eye contact, but they both pointedly avoided looking at me. The young people of color these activists were approaching probably already knew about white privilege. And yet, as a middle-aged middle-class white lady, I should have been their meat, the target of their righteous indignation.

On a recent rare visit, I was walking south of Market in San Francisco,, among a multitude of people on the sidewalks, mostly young, very diverse. Thirty years after I moved away, I wouldn’t have recognized this glossy corporatized area as the gritty warehouse section of old. There were two young civil rights activists of color working the front of a Whole Foods store (!) on Fourth, passing out leaflets, repeating their slogans about fighting white privilege, stopping oppression. They passed out their leaflets to any hip young thing that walked out of the slick Whole Foods, as long as that hip thing was of color, too. I tried to make eye contact, but they both pointedly avoided looking at me. The young people of color these activists were approaching probably already knew about white privilege. And yet, as a middle-aged middle-class white lady, I should have been their meat, the target of their righteous indignation.

Tell me about all the ways I’m privileged and don’t know it. Please. It’s good practice for all of us. They would have been preaching to the choir. I regret that I didn’t stop (late for a meeting, as usual). It could have been genuinely uncomfortable and highly educational for all.

I’ve spent most of my adult life living in other countries, far from where I grew up in the United States. I have been the Other for decades. Here in France, we have a neighbor who hates us. For years, he staked out his territory by positioning his car across all of our parking spots when he visited his girlfriend. He grabbed me once and screamed that “This isn’t Germany! You can’t just come in here and park your car. This is my country.” Okay. I’m not German, but my husband is. At the local kindergarten, our daughter was called a Nazi and bullied by five-year-olds too young to know what that means—but they must have gotten the word from somewhere. Training begins early in bigotry school. I’ve had people get angry at me for what they thought I was or wasn’t, refuse to rent me hotel rooms or shake my hand, treat me with everything from extraordinary generosity to downright animosity because I was a foreigner. There was my neighbor in Japan who used to run away from me in our apartment building so she wouldn’t have to share an elevator with the only white person in the entire town. Despite all of that, I know that any perjorative insult that has been hurled at me hasn’t hurt me because, in a very real way, I made a voluntary decision to move to places that are not my original home. I’ve had at my disposal an array of advantages I have enjoyed because of my skin color, my education, my background.

I didn’t grow up being told I was less than anyone else, ever. That’s a privilege, just like the racism I was taught is a curse. I can’t undo what I was taught as a child any more than I can go back in time and become someone else entirely. But I can make amends by deciding what to keep and what to discard. I can choose—and it’s always a choice—tolerance over fear, because in the long run, fear is a prison with ever-tightening walls. Those walls are made of the bricks we bake every time we indulge a stereotype, even in our heads.

Which walls are you building? And which side of those walls are you on?

P.K. Read is a French-American writer, she lives in eastern France. She has published numerous short stories as well as non-fiction pieces, and blogs on environmental issues, champagne and whisky at champagnewhisky.com.

4 Comments