EMERGING FEMINISMS, A Report on #WeAreHere: The Collective

By Lynden Harris and Madeleine Lambert

*”Collective Voice of the Voiceless”: Campus Violence, Resistance, and Strategies for Survival Forum Contribution*

Inked in black and gold, the words sprawl across a glass wall inside our student union:

IMAGINE sexual violence doesn’t exist. What’s different?

Below the script, green and black sticky notes tattoo the glass.

- I wouldn’t be periodically overcome with the feeling of being dirty.

- Intimacy wouldn’t be a game to win.

- I could flirt without being nervous about “giving the wrong impression.”

- I could walk behind a woman at night without being self-conscious that she likely perceives me as a possible perpetrator.

- I would feel safe going to night classes.

- I wouldn’t need my pepper spray and knife.

- I would be proud of my body—proud to be a woman.

Every day more notes appear. If you pause long enough, a visual chorus begins to emerge: walk, wear, night, safe, alone.

But notice how rarely the answer to “What’s Different?” appears in present tense.

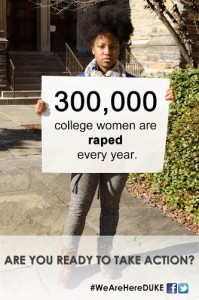

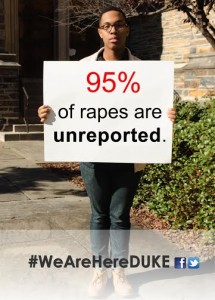

This past fall, my colleague Madeleine Lambert and I offered a new course at Duke University, “Telling Stories for Social Change: Confronting Sexual and Gender Violence.” Housed in the Department of Theater Studies, the class was cross-listed with Public Policy, Women’s Studies, Literature, and Dance. Our aim was to facilitate student exploration into how personal narratives and radical story-sharing can serve as tools for movement-building, advocacy, and policy shifts. We began with a few simple statistics.

- 300,000 women will be raped on U.S. campuses this year.

- Nine out of ten of those rapes will be serial assaults.

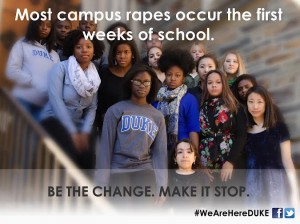

- Most victims will be freshmen.

- Most assaults will happen before Thanksgiving.

Sound bites.

The juxtaposition presented a stripped-down perspective on some commonly held misperceptions. Yes, college is a time of experimenting with relationships, boundaries, sex, alcohol, and more—a messy and liberating period. But contrary to many recent blog posts and articles, confusion over consent isn’t driving the problem.

“Telling Stories for Social Change” was designed and facilitated from a solutions-based perspective. The end to sexual violence is reachable and teachable. The course would provide space for students to uncover and deconstruct personal and societal attitudes and biases related to the issues of interpersonal violence and then utilize their new understanding to facilitate similar integrative pathways for peers. And because this was a service-learning course, students would be learning from community members through oral histories and ethnographies or what we at Hidden Voices call “living listening.”

Whose stories need to be shared? Who needs to hear them? What do they not understand? What blocks their understanding? In conjunction with research and fieldwork, students engaged the Hidden Voices process to consider resonant questions, identify targeted outcomes in their communities, develop a multifaceted action plan to end sexual violence, and gather the community members most affected by violence and most able to forward its end. The students built a collective.

They built #WeAreHereDUKE.

Foundational to Hidden Voices’ process is the precept that all targeted outcomes and action strategies must be personal, passionate, and possible. Passionate gained a whole new meaning once students entered the living listening sessions with victim-survivors, advocates, and service-providers.

Whether we call it engaged scholarship, community fieldwork or co-teaching, this exchange between stakeholders and students is key to informed, participatory action. Issues take on a face and a feeling. Solutions are no longer theoretical but evolve from lived experience, as was expressed the course: “Before entering this class, my attitude toward the subject of rape could best be described as ambivalent, perhaps even apathetic . . . it was too hard to determine who was telling the truth, so I just stayed away from the issue, actively choosing to remain neutral and not take a stand. . . My viewpoint has now drastically changed, and it did so in this class as I began to read and listen to the stories of actual victims.”

“WeAreHere” follows a collective community based statement of purpose: “WeAreHere stands for victims and survivors. We are all victims when any one of us is harmed. WeAreHere stands for allies and advocates. We can take care of each other. WeAreHere stands for men willing to stand up not back. We can affect change.”

With the support of these community “stakeholder” voices, students developed three campaign strategies (social media, public policy, campus events) to realize their targeted outcomes, along with a plan to collaborate in future semesters with other campuses to continue changing the social and political cultures that support sexual violence.

Social Media: Iconic Duke. One cold morning, students gathered on the gothic Chapel steps to photograph the statistics that had most influenced their shifting understanding of campus sexual violence and to pair them with action steps. Seventy-five percent of victims tell someone, usually a friend. Are you prepared to listen? In order to post the photos more widely, the class created the WeAreHereDUKE Facebook page and Twitter feed @WeAreHereDUKE. This fall, students are expanding the sites as story-sharing vehicles.

Policy: The policy initiative identified two critical areas for change: reporting and prevention. In conjunction with Duke victim-survivors, and with guidance from Duke Student Government, the Center for Sexual and Gender Diversity, the Women’s Center, and Duke Support, the policy group surveyed students about attitudes and experiences with the campus reporting process. Based on response data the policy initiative drafted a letter recommending fundamental and feasible changes to the reporting and the hearing-resolution processes. Students presented the survey results and recommendation letter to the university Task Force on Gender Violence, which included Duke’s Title IX Coordinator, Gender Violence Intervention Coordinators, Chief of Police, and Head of Student Affairs. The presentation sparked dynamic discussions, which continue, and contributed to several tangible changes in the reporting and the hearing-resolution processes, including increased inclusivity in the language used and the fulltime hiring of a woman in the role of Title IX outreach and response.

The policy group also focused on prevention. Expanding the student-facilitated Prevent Act Challenge Teach (P.A.C.T.) training was one of the class’ targeted outcomes. P.A.C.T. training helps students identify situations of concern and provides tools to encourage successful interventions. In response to the policy letter and presentation, approximately one-third of the 2015 incoming freshman class were P.A.C.T. trained.

Campus Events: Campus actions included the interactive vision-sharing wall Imagine, a T-shirt campaign, a zine publication, and a community performance.

T-shirt campaign. More than two hundred faculty members, student leaders, and athletes wore T-shirts emblazoned with the hashtag #WeAreHereDuke. At the beginning of class, faculty read a statement about the campaign, which began: “One in four women will experience rape. Picture four women you love: your mother, your sister, your best friend, your girlfriend. Which one do you choose?”

Inviting faculty to participate in this movement opened the door to some new revelations. Most faculty appreciated the invitation to participate. Most were concerned with the impact of sexual violence on their students and their families. And most felt poorly prepared to respond. As one faculty member stated, “I wore the shirt tonight and read your statement to the class. . . I want to wear it tomorrow and Wednesday and each time someone asks me what the shirt means, I will give them a copy of your statement.”

The Zine. Sketches, stories, and statistics about sexual violence at Duke. One opening piece was reveling in particular. A female class member shared this male student’s response to an informal campus climate assessment: “We want to respect you, but if you don’t make us then we won’t … I searched for some sort of hidden positive meaning, but the translation was clear. I am going to push you to give me as much as you are willing to give. And if you are unsure of yourself, I am going to get more than you are willing to give because you have no idea what the fuck you are doing.”

Performance. Each student wrote two performance pieces: first, a monologue based on the listening sessions with victim-survivors, activists, lobbyists, and artists; and secondly, a personal narrative tracing their own arc of change during the course. The final evening of the semester, we welcomed a public audience into the theater to hear these passionate, powerful, and personal presentations. Within minutes, students, workshop participants, administrators, faculty, and community members filled the space. The audience was multigenerational, ethnically diverse and with a robust representation of men. This was not the choir we were preaching to. Nor were we preaching. We were offering an opportunity for connection and reflection. Scores of potential audience members had to be turned away, an unfortunate reminder that open spaces for this kind of community connection and reflection are far too rare.

The student who confessed to feeling ambivalent about the issue mentioned above closed her piece this way:

Knowledge has changed my ambivalence. A survivor [I interviewed] spoke of the repercussions she experiences thirty plus years later.

As much as we’d like to think ‘I am over it. I am done. I don’t need to hold onto that,’ I think our bodies and our hearts and our souls have a much harder time letting go.

I am proof that people’s perspectives can change. I am now an advocate of victims’ rights. . .

After the students presented their narratives, we opened the floor to conversation. The first three questions were “Are you teaching this course again?” and then, “No, seriously are you teaching this course again?” We responded that we would teach the course until we no longer needed to. When we asked for other questions or comments, a woman found her way to the microphone and uttered five words. “Someone just told my story.” She paused. And was unable to say more. #WeAreHere is a powerful thing to be part of.

Afterward, the survivors who had collaborated with the course requested photos with their students—another marker on their long journey. It was an honor and reckoning for the students to recognize their personal agency, as vehicles of change for the survivors, for the audience, and for themselves. Over and over we heard students say, “This is the first time I’ve been in a class where what I create has real impact. What we do in this class affects actual change.”

Transformation is powerful to experience. Ending sexual and gender violence begins with envisioning a new way of being in the world. In present tense:

- I can wear what I want, when I want, where I want, AND NO ONE HARASSES ME.

- Men step up, not back.

- Gender roles are redefined: Masculinity/male sexuality will no longer be synonymous with violent behavior or uncontrollable sexual urges.

- Women are called women, not girls.

- Everyone is free to dance!

- I can forget.

**********

Lynden Harris is co-instructor for “Telling Stories for Social Change: Confronting Sexual and Domestic Violence” at Duke University. During her decades of work as an artist facilitating community connections, Lynden developed the Hidden Voices Process, a participatory workshop model designed to empower change through collective visioning and collaborative action. This process facilitates a dynamic exchange between documentary, art, and community that allows for a multiplicity of voices and a multiplexity of understandings. Lynden is the founder and director of Hidden Voices.

Lynden Harris is co-instructor for “Telling Stories for Social Change: Confronting Sexual and Domestic Violence” at Duke University. During her decades of work as an artist facilitating community connections, Lynden developed the Hidden Voices Process, a participatory workshop model designed to empower change through collective visioning and collaborative action. This process facilitates a dynamic exchange between documentary, art, and community that allows for a multiplicity of voices and a multiplexity of understandings. Lynden is the founder and director of Hidden Voices.

Madeleine Lambert is a theater artist and teacher. She is the co-instructor for the course “Telling Stories for Social Change: Confronting Sexual and Domestic Violence” at Duke University.

Madeleine Lambert is a theater artist and teacher. She is the co-instructor for the course “Telling Stories for Social Change: Confronting Sexual and Domestic Violence” at Duke University.

Since 2003, Hidden Voices has collaborated with underrepresented communities to create award-winning works that combine narrative, mapping, performance, music, digital media, animation, and interactive exhibits to engage audiences and participants in explorations of difficult issues. Hidden Voices creates venues where stories from those rarely seen and heard by mainstream society take center stage. These life-changing stories provide insight about identity, place, and access. They help us understand the unrecognized, unfamiliar, and displaced among us. Hidden Voices’ projects include narrative, performances, interactive exhibits, audio and walking tours, critical mapmaking, print and digital media.

Pingback: EMERGING FEMINISMS, An Introduction to the "Collective Voice of the Voiceless" Forum on Campus Violence, Resistance, and Strategies for Survival - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire