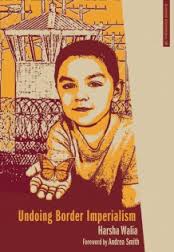

A Review of “Undoing Border Imperialism”

By Erin Durban-Albrecht

On the morning of October 11, 2013, activists of all ages in my hometown of Tucson put their bodies on the line—chaining themselves to the front wheels of deportation buses and the gates of the federal courthouse—in order to throw a wrench in the impressive machinery that criminalizes brown and black immigrants in the United States. I participated in the action as a street medic, someone in a support team who cares for activists on the frontlines, and as one of several hundred people just at that site contributing to efforts with the goal to shut down Operation Streamline for the day.

Operation Streamline is a U.S. Department of Homeland Security program that fast-tracks criminal prosecution of undocumented immigrants who are subsequently warehoused in private prisons in the United States. The action to shut down this dehumanizing program that makes a joke of due process was part of an impressive grassroots movement against the fracturing of families and communities that takes place each time another person is deported. Under the banner of Not One More Deportation (#Not1More), many similar actions have taken place across the country in recent years to protest President Obama’s regime of deportation—more people have been deported under his administration than any other in history. #Not1More is just one manifestation of successful campaigns for immigrant justice instigated by activists in transnational movements that address the myriad social justice issues connected to migration and citizenship.

At a time when nation-states in the global north—and increasingly in the global south—are finding new and creative ways to dispossess different populations of citizenship, it is imperative that activists on the frontlines of these movements document their struggles, successes, and visions for a different world. This is precisely what Harsha Walia and her collaborators—many of whom are affiliated with No One is Illegal (NOII)—have done in Undoing Border Imperialism.

The book has a substantial agenda pertaining to the performance of undoing borders, which Walia clarifies as “the physical borders that enforce a global system of apartheid and…the conceptual borders that keep us separated from one another” (2). The introduction and first chapter outline a theory of border imperialism through an assemblage of social theory, social movement histories, poetry, and Walia’s personal narrative as a South Asian activist in Canada who has participated in social movements for more than a decade. Border imperialism is a way of theorizing state-centered discourses of migration and migrants as well as bordering practices that extend well beyond walls and fences with barbed wire, Coast Guard patrols, and other securitized zones throughout the world running along the scars of state-imposed partitions.

The second, third, and fourth chapters detail various efforts of activists to contend with the effects of border imperialism in migrant justice work. They collectively comprise the most interesting renderings of social movement work that I have ever read, digging into the gritty complexities of group leadership, intra-group dynamics in alliance building, strategies for radical political work, carrying out successful campaigns, and various ways of working to decolonize social movement work.

The final chapter, “Journeys Towards Decolonization,” offers a prefigurative vision of creating the worlds that we want to see through healing justice—liberatory self-care that focuses on collective well-being with the grinding conditions of oppression (266-267)—and revolutionary love as a framework of interconnectedness stemming from social movements that leads to creative forms of resource redistribution (e.g., community kitchens, collective family care) intended to disrupt the harms of individualism.

It is worth noting that Undoing Border Imperialism is itself a model for this kind of disruption; while Harsha Walia’s name graces the cover, I would describe her labor in relationship to the book as one of a curator that carefully creates space for many different voices in the service of a larger vision. The book’s polyvocality comes through in the art, poetry, and personal narratives of many social justice organizers integrated throughout that enhance the analysis of the text. To provide just a few examples: the forward was provided by Indigenous feminist activist and UC Riverside professor Andrea Smith, the graphic art of Xicana social justice activist Melanie Cervantes opens each section of the book, and the writing of queer, disabled, Sri Lankan femme Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha amplifies the analysis of border imperialism alongside that of more than a dozen other cultural workers. One chapter, “Waves of Resistance,” is formatted as a roundtable with fifteen migrant justice activists with different entrances into conversations about organizing.

It is worth noting that Undoing Border Imperialism is itself a model for this kind of disruption; while Harsha Walia’s name graces the cover, I would describe her labor in relationship to the book as one of a curator that carefully creates space for many different voices in the service of a larger vision. The book’s polyvocality comes through in the art, poetry, and personal narratives of many social justice organizers integrated throughout that enhance the analysis of the text. To provide just a few examples: the forward was provided by Indigenous feminist activist and UC Riverside professor Andrea Smith, the graphic art of Xicana social justice activist Melanie Cervantes opens each section of the book, and the writing of queer, disabled, Sri Lankan femme Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha amplifies the analysis of border imperialism alongside that of more than a dozen other cultural workers. One chapter, “Waves of Resistance,” is formatted as a roundtable with fifteen migrant justice activists with different entrances into conversations about organizing.

Regarding the book’s other interventions in terms of dominant modes of thinking, Walia begins by reframing discourses of immigration that concentrate on the generosity of Western states (e.g., the United States, Canada, and those in the European Union) for providing refuge to huddled masses yearning to breathe free of political violence and poverty elsewhere. These discourses erase the culpability of these same nation-states in creating the conditions—through colonization, structural adjustment and financialized imperialism, political violence and many more means—that coerce or force mass displacements and migration as an individual solution to a systemic problem. Walia proposes an alternative framework for understanding migration, borders, and bordering practices as ways of extending and imposing “unequal relationships of political, economic, cultural, and social dominance of the West” (41-42). The framework weaves together four different threads of analysis detailed in the chapter “What is Border Imperialism?”: the displacements already mentioned coupled with the securitization of borders to the further detriment of those who have been displaced, the criminalization of immigration and immigrants in relationship to a growing prison industrial complex, the racialized hierarchy of citizenship, and the state-mediated exploitation of migrant labor that benefits transnational capitalism (5).

The real heart of the book comes in the subsequent chapters, however, which provide insight into on-the-ground practices of countering border imperialism from organizers with No One is Illegal (NOII). NOII is a decentralized, all-volunteer coordinated network of migrant justice groups in more than ten locations in Canadian provinces that share a political vision “rooted in anticolonial, anticapitalist, ecological justice, Indigenous self-determination, anti-occupation, and antioppressive communities” (98). While focused on migrant justice, the analytic framework of NOII connects the network to various social movements, including those for reproductive justice and gender liberation. These connections are clear in the ways that Walia describes in the early chapters the impacts of border imperialism with acute detrimental impacts for women, people of color, Indigenous peoples, and poor people. Her later discussions about NOII grapple with the impacts of heteropatriarchy, white supremacy, and settler colonialism in direct support work for those effected by detention and deportation and long-term efforts to secure “status and access for all” (111). The chapters detail campaigns spearheaded by NOII similar to #Not1More, such as Education Not Deportation to prevent policing on the basis of immigration status in elementary and secondary schools and Shelter Sanctuary Status to prevent immigration officers from entering women’s shelters in Toronto.

One of many strengths of Undoing Border Imperialism is this intertwining of theory and praxis, an accurate reflection of the dynamics of transformative social movements where theory informs practice and practice informs theory. Another strength is the sustained connections the book makes between struggles for Indigenous sovereignty and migrant justice. Following the lead of Indigenous activists and scholars, Walia theorizes settler colonialism—a particular form of settlement wherein those with relative power occupy and dominate the territory they inhabit to the detriment of Indigenous peoples—as part of border imperialism. While these connections are part of conversations on the ground where I live since the border crosses the land stewarded by the Tohono O’odham nation, they rarely appear in scholarship and popular texts about immigration. Among the kinds of crosspollination mentioned in the book are the occupation of Border Patrol Headquarters in Tucson by Indigenous activists in 2010 in response to Arizona’s regressive “show-me-your-papers” law (xi), the issuing of “Original Passports” to asylum seekers by Indigenous organizations in Australia (37), and the “No One is Illegal, Canada is Illegal” framework that came out of the 2005 International Indigenous Youth Conference in Vancouver (125). Walia notes that working in solidarity with Indigenous activists is a necessity for truly transformative migrant rights work. “As a migrant…I realize that migrant justice will be short lived if gained at the expense of Indigenous self-determination” (130). She goes on to mention the ways that NOII has supported Indigenous organizing beyond moments of crisis when there tends to be more nonnative support.

There is always more that one could ask for from a book that covers as much ground as Undoing Border Imperialism, and what I offer here is not meant as a critique as much as a complement. While Walia offers queer and trans social movements, among others, as exemplars of creating transformative change and undoing border imperialism, the analysis of the relationships of sexual difference and transgender embodiment to border imperialism is lacking in the chapters that outline the book’s theoretical apparatus. The connections become more apparent in the later chapters, especially through the work of San Francisco-based collective Horizontally Aligned Very Organized Queers (HAVOQ) and in fragments from queer postcolonial studies. I would have liked for this work to be incorporated at the forefront of the book, perhaps along with queer and trans* migrations scholarship by Eithne Luibhèid, Karma R. Chavèz, Trystan Cotton, and others. At least these fields of scholarship would be beneficial to read alongside Undoing Border Imperialism to get a deeper sense of the ways that gendered, sexualized, and racialized bordering practices overlap with one another in profound ways and also to bring into perspective queer social movement work against border imperialism that can be sidelined in queer and trans* migrations scholarship.

Overall, Undoing Border Imperialism is a model for intellectual work with strong commitments to social justice. Harsha Walia writes with tremendous passion and knows how to tap into experiential knowledges to create connections between movements that people may or may not be part of. I would highly recommend the book to anyone doing migrant justice work, as a way to think through different movement dynamics and learn from the successes of NOII. It might be a difficult read for people steeped in mainstream paradigms that equate social justice with tolerance and equality, but I would still lend a copy to folks who are interested in what more radical and transformative work can look like and the labor involved in that work.

To read an interview with Harsha Walia in The Feminist Wire, click here.

Details about the book:

Undoing Border Imperialism by Harsha Walia

AK Press 2013

321 pp.

$16.00 U.S.

______________________________________

Erin Durban-Albrecht is a queer, feminist activist and cultural worker living in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands who is inspired by participation in social justice movements as well as reading scholarship in critical ethnic studies, queer postcolonial theory, and transnational feminisms. Erin is also a PhD candidate in gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona in the final stages of writing a dissertation, “Postcolonial Homophobia: United States Imperialism in Haiti and the Transnational Circulation of Antigay Sexual Politics,” that focuses on various transnational social movements—such as those for LGBTQI rights and those for neoconservativism—in postcolonial Haiti and its diaspora.

Erin Durban-Albrecht is a queer, feminist activist and cultural worker living in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands who is inspired by participation in social justice movements as well as reading scholarship in critical ethnic studies, queer postcolonial theory, and transnational feminisms. Erin is also a PhD candidate in gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona in the final stages of writing a dissertation, “Postcolonial Homophobia: United States Imperialism in Haiti and the Transnational Circulation of Antigay Sexual Politics,” that focuses on various transnational social movements—such as those for LGBTQI rights and those for neoconservativism—in postcolonial Haiti and its diaspora.

Pingback: An Interview with Harsha Walia - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire