Feminists We Love: Betty Makoni

Muzvare—Her Royal Highness Betty Makoni, has been honored by her traditional Chiefs in Makoni village and conferred with the title Princess. She is an international human rights and girl child rights activist who wears many hats. She is Founding Executive Director of the Girl Child Network Zimbabwe and from 2009 became Chief Executive Officer of Girl Child Network World Wide. The organization champions the rights of girls in Africa and around the world through programs that empower. Founded in 1998, the Girl Child Empowerment Model has been used and replicated by many organizations, and Betty Makoni is in great demand as a speaker, consultant, and trainer.

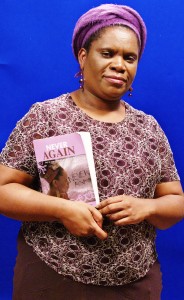

The author of the autobiography Never Again (2012), Betty Makoni is a 2009 CNN Hero for Protecting the Powerless, an honor presented to her by Nicole Kidman. She has received more than 30 global awards for her work, including a prestigious United Nations Red Ribbon Award that also honored the Girl Child Network for having the most innovative strategy for gender equality. Betty Makoni is an Ashoka Fellow, and Newsweek named her one of 150 women who shake the world.

Betty Makoni has dedicated her life to service and sits on the boards of numerous organizations including Restored UK and the Zimbabwe Women’s Network UK. She is the first woman to serve as the Global Ambassador for UN 19 Days of Activism for prevention of abuse and violence against children and youth. Recently she was selected to be one of the UK gender-based violence experts for the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative. Every Monday, she hosts a show on Pamtengo Radio focused on empowerment of girls and women.

A survivor of rape at age six and an orphan by age nine, Betty Makoni published a book of poetry, A Woman, Once A Girl: Breaking Silence. The poems narrate her lived experiences as well as the stories she’s heard from many girls and women around the world. As she says on her website, “The time to break silence is right here and now.”

During a visit to Tucson, Arizona, to talk about the Girl Child Network Worldwide and her progress in replicating the model in Africa and in some U.S. colleges, and to screen the film Tapestries of Hope, Betty Makoni graciously made time for an interview with TFW Collective Member Mason Casper-Milam. Here is their conversation.

Mason: What can you tell me about the Girl Child Network?

Betty: The Girl Child Network is a grassroots organization that I and my 10 students started in 1998. I grew up in the high-density suburb of Chitungwiza, and I realized that girls there were dropping out of school. And also I had my own personal background where I had been raped as a child at age six and I lost my mother at age nine. So I had the determination that one day I would change the situation; one day I would be a woman standing in front of girls to say this should not be the way of life.

We started with ten girls, and then ten girls multiplied into twenty girls. Twenty girls multiplied to fifty. After we got fifty girls, they started telling their sisters in other schools. So it became a movement spreading all around the high-density suburb and then it spilled over to villages. And as you know, villages are quite marginalized with many underprivileged girls. But it was very heartening to go into a village and see a seven-year old girl saying, “Empower the girl child, power the world.” They started doing slogans. It was a movement for young girls, which started in a classroom but transmitted through their own power to every village in Zimbabwe.

We started with ten girls, and then ten girls multiplied into twenty girls. Twenty girls multiplied to fifty. After we got fifty girls, they started telling their sisters in other schools. So it became a movement spreading all around the high-density suburb and then it spilled over to villages. And as you know, villages are quite marginalized with many underprivileged girls. But it was very heartening to go into a village and see a seven-year old girl saying, “Empower the girl child, power the world.” They started doing slogans. It was a movement for young girls, which started in a classroom but transmitted through their own power to every village in Zimbabwe.

Mason: Why do you think the Girl Child Network has been so successful?

Betty: When you touch something you believe in, something that has happened to you, there is no way you can separate yourself from the cause. You also become the cause. And then, if you meet other young girls who are determined to move from being perceived as victims into young leaders, you also begin to feel the change coming. So every time they change, you are motivated to do more. I had girls who were aged six, seven, or eight, and I saw them to their graduation for the first time in the high-density suburb of Chitungwiza. Then I said to myself, why can’t I set up a center they call their own so that I can continue empowering and educating more girls? So we also created our own spaces, our own infrastructure in Zimbabwe.

And the second thing we realized in Zimbabwe is that as girls, the parents prefer boys to us and so we don’t inherit anything; we will not inherit whatever the country gives us. So we started off building girls’ empowerment villages, we started building girls’ grinding mills, and most of the money that we used in our projects was not all from donations. It also came from girls working hard to generate their income. So, something that comes from your hand stays longer than something that comes to you on a silver plate. Because then you learn to not just sit back. So I must say that success comes from your own personal story. Success comes from believing that my change is another girl’s change. And then success comes when you’ve got ownership of something and you are able to control it. You must own buildings. You must own the mission. You must own the people that are also going to come to listen to you. Parents, traditional leaders, and all members of the community came to listen to us and changed their attitudes towards girls and pledged to treat them as equals. They came to listen to Betty talk! That may seem a small achievement, but in a situation where no one respected the rights of the girl child we made a major breakthrough. We were very successful in changing attitudes in the home, school, and community where girls lived and grew up. That change then spread in the whole country like veld fire.

I think sharing the model with many women and girls gave us success we can point to directly and indirectly. If you see the many initiatives that we helped start in Zimbabwe, Africa and many parts of the world, we can point to many we inspired. We have success in activating many to take action to protect girls. So transitioning from me as a leader has taken quite a while, but due to the nature of the movement I had created, I now realize that girls who have grown to be women leaders have gone on to form many similar networks. One clear example of a success story is my former student Memory Bandera who is now running Girl Child Network Uganda. I believe that to be successful is not to own the organization single-handedly; you give skills and motivation to many others to do what they want and provide the guidance. That is the legacy I leave in the world, to form something and inspire many others to do it their own style and way without even asking for credit.

I think sharing the model with many women and girls gave us success we can point to directly and indirectly. If you see the many initiatives that we helped start in Zimbabwe, Africa and many parts of the world, we can point to many we inspired. We have success in activating many to take action to protect girls. So transitioning from me as a leader has taken quite a while, but due to the nature of the movement I had created, I now realize that girls who have grown to be women leaders have gone on to form many similar networks. One clear example of a success story is my former student Memory Bandera who is now running Girl Child Network Uganda. I believe that to be successful is not to own the organization single-handedly; you give skills and motivation to many others to do what they want and provide the guidance. That is the legacy I leave in the world, to form something and inspire many others to do it their own style and way without even asking for credit.

Mason: When you started the Girl Child Network, did you believe it would become successful?

Betty: What happened was, when I was a girl vendor, I kept on seeing a vision in my dream where girls were running to me in their townships. I was like a woman leader coming out from a white car always and having to travel places where girls would run to me. Each time in my dream, I came out of the car and thousands of girls rushed to me saying, “Auntie Makoni, Betty Makoni!” I didn’t know what it meant, up until I started with a girls club at school and then saw them coming in large numbers. I did think that it would grow, but I wasn’t really sure how far. So when it eventually started growing, it outgrew me! It became bigger than the small group I had wanted to form. But my heart was bigger and my vision burning inside that I wanted to do something to empower girls, like what happened with me. So, I must say, sometimes when we come from a situation where we’ve been victimized, we do things at a minimum when things push them to a maximum. That is what I’ve come to believe.

Mason: Can you tell us about some obstacles you faced in the making of the Girl Child Network?

Betty: There were many obstacles, but I will just pick out a few. First thing that challenged us, we were not even allowed to use the school premises as girls for our meetings—that space was denied from day one. We were not allowed to use the school bus for our trips. And back then, my girls didn’t know that to be a feminist was a very good thing, so when they were called feminists, we would lose girls from our girls club. They believed they would never get married as feminists, so some of them gave up. We lost membership when I was forming the organization because of the stereotyping that goes on with women speaking out. And a lot of boys and male students and their teachers jeered at girls who attended girls clubs. That also caused the girls to lose self-esteem. And as we went up in our success, we also had a lot of people who believed in patriarchy and who thought that we were overthrowing them politically, like our government. I realized this when I was arrested, and during interrogation by Law and Order of the Police I was asked if one day I wanted to run for Presidency. I realized they had misinterpreted why we were in existence. We were in existence to support vulnerable girls, but they interpreted it that we were forming a big political party…that one day we would be a threat to national security! And so, I was persecuted in Zimbabwe and I was arrested four times in two years. I spent ten days in jail going through interrogation and harassment for my passion to assist girls. And each time you come out of such interrogations, you would find that the only newspaper in the country had written some negative things about you and worse still, you were never given a chance to present who you are. Doing activism of any kind in a situation where you work against certain beliefs has zero support.

So imagine that instead of spending my quality time helping girls, I was constantly in police custody on false allegations of working against government, which was not true because if I am helping girls in my country, I am also complementing government efforts. All those girls you lead also begin to question who you are because of the lies they meddle through the Internet and press. My life in Zimbabwe would not last if I had stayed. Yes I want to be a hero, but having given my life to working for girls I would not want to risk becoming a dead hero. As much as I struggled for girls, I also struggled to be allowed to save my life. And so, every time I was arrested, the paper lied about something else. I suspect that someone had a plot to bring me down and sadly it was women at the forefront of this plot. I understood how bad the plot was and then I decided to make peace, to leave the country before it became worse and create a space and a platform elsewhere. There was a big challenge as to where to establish my new platform, because not even a single donor or friend was willing to take the risk except Ashoka, where I am a fellow. I relocated to Botswana, and physical and emotional disconnection from my girls pained me because it meant I was coordinating the work through others who were maybe not willing and able to do as much.

And then another challenge we faced, we had thousands of girls who needed assistance. Sometimes you would get big donors give you money, but only money for a workshop in a big hotel. Then you are in a situation where you are faced with a girl who wants to be in school and you have nothing to give to her to relieve the immediate pain and deprivation. You would think twice. Should I go to the hotel for a workshop as per donor contract, or should I go to the school and help the girl? So as a leader who had suffered like the girls, I was really tempted many times to go to the school. I would definitely borrow the money to pay for school fees, because I thought that girls’ education was more important. I am beginning to see also why rural areas were a big challenge, especially on those occasions we visited girls clubs and realized most of the girls were starving at school and had walked miles to meet us. I was much challenged by rural girls and their resilience. No funding fitted their priority needs at all.

There was also that impression created by vehicles we used, that having a car showed we had money and we were very rich. So, people did not see this as connected to their own development, and also due to poverty one was so determined to find a selfish way to gain access into the organization in order to benefit personally. They started taking it as a rich project. Just a car has got status in Zimbabwe, or in Africa. So that really challenged us in terms of security, where just anybody would come and demand money from us at gunpoint, at knifepoint, or in the last death threat I got days before I decided to go into exile where someone demanded over US$8,000 as life protection fee against so called state agents. It became a nightmare to think with all threats going right in my phone whether I would last. This created a lot of anxiety in me; no wonder I left to settle in Botswana and establish a satellite office where I could work with no such threats.

Then another, last challenge I want to share is all the thousands of men we pushed into going into jail became our rebels, and in all instances where we pushed for them to be jailed for raping girls their relatives hated us. The more girls we rescued out of rape, the more enemies we created. And all those high-ranking officials in politics hated us too, to an extent of planting an operative inside our organization to create and spread falsehoods. And so all those obstacles undermined our work so much, because at one time I had to fight to stop persecution from within and outside the organization. Media blackout was imposed on us and we are not allowed to be covered on all positive things we had achieved for Zimbabwean girls; and no wonder every positive we achieved was portrayed in a negative way, sometimes even with so-called independent media working under guise of operatives. A media and Internet tactic was used to attack me personally, and it is mere hatred that made some people work day and night online to defame me. If people thought only a gun or jail targets a human rights defender, they may want to rethink how the Internet is being abused by online newspapers to target our work. That is why Zimbabwe never got to know what we were doing, because we were not allowed to be covered in the news. After many years of our story of saving girls’ lives being changed to appear as if we did something wrong, we have now started to share our story and provide lessons for many other girls and women working in same situations. I am so sure the familiar story of Malala [Yousafzai] should also get the world thinking that speaking out against abuse of girls everywhere in the world will never be an easy task at all.

Mason: How do you think the Girl Child Network will change over time?

Betty: Very, very brilliant question. I am seeing young girls like you taking over. I am in my 40 years. We need new energy. So, we are globally, strategically situating young girls to take over the leadership of the network. We want to see as many Betty Makonis of every religion, every class, every color, every background. We want to see just as many replications. I see it in masses in countries like America and I see it huge in Africa, because Africa is now our focus. I also see Girl Child Network with a big headquarters where you have got lawyers, doctors who are examining all the cases happening in the world. And then I see myself retired and admiring the work. [Laughter]

Mason: So, what are your hopes for the Girl Child Network?

Betty: My hope is that it is taken up in every village. My hope is that we continue to give hope to girls in Africa who cannot help themselves. My hope also is to ensure that those in war-torn countries and countries in conflict are rescued in time, so that they walk in the fullness of their potential. My hope is that girls like you should be speaking out more. I didn’t know there are big voices like this in the world, and we need you to come out quick and really, really set up yourself. So my hope is in young girls who are already leading.

Mason: Why did you decide to choose to write a poetry book as well as an autobiography?

Betty: Oh, good question. I’ll start with the poetry. When I was a child vendor on the street, I used to call out, “tomatoes, onions, tomatoes, onions,” so I thought it was really poetic. But it was poetic about ending poverty. So, when we do poetry on the streets as vendors, we don’t normally value ourselves, but it is a protest symbolically. So, when I grew up I looked to package myself and I said, this is how I used to speak out. Why can’t I teach girls to speak out the same way? So there are also girls who write poetry. In my book, I include one poem called “The Girl Child,” told by one of the young girls, aged eleven years in Zimbabwe. And what I see in poetry is that it is short verse, it’s to the point. It’s the feeling; it’s the passion; it’s the emotion. And whenever I feel that the situation is tragic, like what I saw with Sandy Hook with those children being shot down, my only appeal is poetry. So I write poetry for the children. That is how I could handle the situation. Otherwise, without poetry I am like a cancer patient without chemotherapy.

As for the autobiography…I found that too many people were interpreting my story in wrong ways, because many got to know about me through word of mouth. I knew I would not be the topic of oral history in this twenty-first century where technology puts our legacies straight to inspire generations to come. I knew I could share my story in an empowered way and inspire millions of survivors across the world to do the same, and so I focused first on how I had empowered myself to be where I am and what I would do as a lifetime job to empower girls using my story. But as you can see, my story was being told in so many wrong dimensions and with inaccuracies right in my face. And I just wanted to bring my story in one book in the way I saw it happening and with truth and only truth. So when people see me they say, the once poor girl who is now a global activist had this to overcome to be where she is.

As for the autobiography…I found that too many people were interpreting my story in wrong ways, because many got to know about me through word of mouth. I knew I would not be the topic of oral history in this twenty-first century where technology puts our legacies straight to inspire generations to come. I knew I could share my story in an empowered way and inspire millions of survivors across the world to do the same, and so I focused first on how I had empowered myself to be where I am and what I would do as a lifetime job to empower girls using my story. But as you can see, my story was being told in so many wrong dimensions and with inaccuracies right in my face. And I just wanted to bring my story in one book in the way I saw it happening and with truth and only truth. So when people see me they say, the once poor girl who is now a global activist had this to overcome to be where she is.

I didn’t want the simple story to be controversial. I didn’t want the simple story to be one newspaper page article. I wanted it to be 600 pages so that young girls dig into me, dig into truth. I wanted also generations of children to study from aspects of taboos and norms that we are not allowed to talk about. I opened up on most of them. These are issues that some people may think are embarrassing, but to me they are empowering. Once you say out something, you heal. And also, some people donate body parts like kidneys or whatever. I wanted to donate my story like those who donate their body parts to save lives. I wanted it so that any child in any part of the world can click on the link and download it even for two dollars and read it on their own and live and be inspired. So I am donating my life to the world and especially to those girls trapped in situations of man-made disasters like poverty and violence.

Mason: What you said about the shooting in Connecticut…what are your thoughts on the shooting?

Betty: My own thought is that this is a direct fight against feminism. I am looking at the numbers here and 18 females and six males. And first of all, he shot his mother. Someone who directs anger against his mother is someone who is not mentally disturbed, according to me. We cannot limit him to that. We can say he is angry at the female race. And when you see the way he came to the school and the fact that he knew it was an elementary school and he knew very well the majority were females, I see him more of a patriarchal bully than a person with a sincere mental health problem. So, again, he came to attack, and the majority of his victims are female. So, I can say as a woman that people should look at it from a gender-based violence perspective and not only from a mental health perspective. I don’t know what kind of mental health that would make you kill your mother and then move on to kill other female teachers, including the principal. Because the principal of the school as the authority is what he tried to challenge very consciously. If he had the guts to go into a school on a planned mission, it speaks volumes about how vulnerable women and girls are in the United States of America to such men be they with guns or not. And I think it is a very strong warning to what may happen in the future in terms of attacking womanhood, just like in the case of Malala. So, I would actually say it was womanhood that was under attack. I saw the beautiful faces of the little girls and I cannot go to my computer, I cannot go to the television to face this pain. I don’t want to feel pain. It’s painful, it’s heartbreaking. And I can’t imagine any little child age six down on the floor and with multiple gunshots. Because with mental health, sometimes when you shoot once, you begin to shake; but this one looks like someone who was really trying to do that.

Mason: The last question I want to ask you today is, what advice would you give girls my age in America? What can we do to help the Girl Child Network?

Betty: First, I will start with the advice I can give to you as young girls. I really want you to see the male leadership at the top as something you can achieve. There has never been a female president in America, which is sending a very bad message to the whole world. We want you young girls to think that what a boy can do, you can also do when you are grown up. Don’t leave anything to chance. And we want you to really, really think about male dominated fields – science and mathematics. I always come here and I see no pilot who is a female. I don’t know why we are afraid to cross oceans. So, if boys see that you are afraid to do something, they will actually take advantage.

And then, I would actually say if there are any means for you to protect your delicate bodies and not expose yourself to sexual activity, which is an adult activity, I would advise you to really, really protect yourself. Because once you are in sexual activity, you reduce your performance academically. And then, if you are abused as a girl and forced to do something that you don’t want, quickly tell someone you know: your mum, your dad, the police, school teacher, principal, and keep telling them because some adults don’t believe kids.

And then, I would actually say if there are any means for you to protect your delicate bodies and not expose yourself to sexual activity, which is an adult activity, I would advise you to really, really protect yourself. Because once you are in sexual activity, you reduce your performance academically. And then, if you are abused as a girl and forced to do something that you don’t want, quickly tell someone you know: your mum, your dad, the police, school teacher, principal, and keep telling them because some adults don’t believe kids.

And I really advise all the girls in America to come out in your large numbers. We have a crisis happening in Africa with the girls, and let’s all join hands and work together. Whatever you can do from here. Write letters, write a book, write an article like you are doing already. Write, do advocacy, form girls clubs, anything; anything you can do to motivate them. Also, technology brings us together; I’m hoping that a lot of American girls can form girl-friendly Facebook groups – not pornography. So that you set a good example. What are the current priorities for girls is development. So, I’m hoping you come in large numbers to help out because in this part of the world you have resources….pencil and pens you can put together. My life was changed by a little girl who gave me a pen, a pencil, and a mathematical set. So, I see your thoughtfulness as something we should value and it should gain more momentum to just reach out.

We have a campaign to raise funds for girls not in school in Africa, and your donation of one U.S. dollar per year goes a long way. It is girls who are building this fund and it is girls who are also managing it. So feel welcome from wherever you are to contact us so that we can register and work with you on our first ever Girls Empowerment and Education Fund.

________________________________________

Mason Casper-Milam is a member of the TFW Collective and a sixth-grader in Tucson, Arizona. She enjoys singing in chorus, working on yearbook, and roughhousing with her dog Beaumont. She looks forward someday to being an Egyptologist, a cardio-thoracic surgeon, President of the United States, or maybe all three.

Mason Casper-Milam is a member of the TFW Collective and a sixth-grader in Tucson, Arizona. She enjoys singing in chorus, working on yearbook, and roughhousing with her dog Beaumont. She looks forward someday to being an Egyptologist, a cardio-thoracic surgeon, President of the United States, or maybe all three.

Mason is grateful to her parents, William Paul Simmons and Monica J. Casper, for their help with this interview, and to Deborah Neff, who hosted Betty Makoni and welcomed people into her home.

0 comments