Fear of a Black Body

Hank Willis Thomas

“Suspicious;” “he feared for his life;” “it looked like a weapon;” and “it was a dangerous situation.” Such explanations and sources of defenses have become commonplace #every36hours. As black men and women die at alarming rates, amid claims that racism or race is not at issue, those who want to explain away these deaths, disregarding the injustice and lost futures, continue to rationalize and blame, criminalizing black bodies even, perhaps especially, in death.

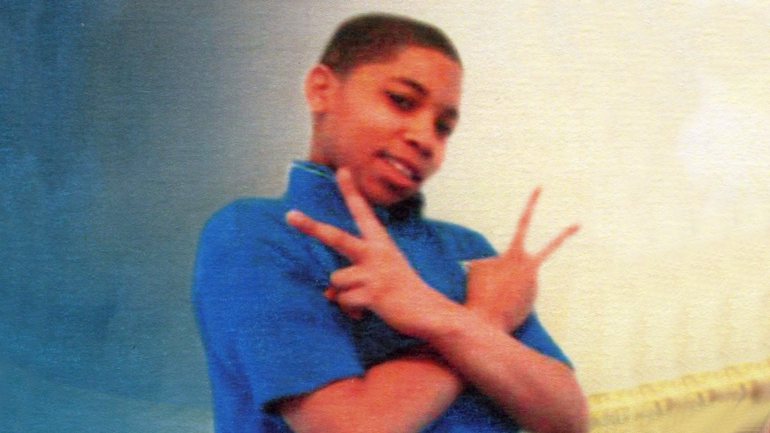

Jordan Davis spent his last night hanging out with a group of his friends. He, like many American youth, spent the evening laughing and chatting. Shortly after his family celebrated Thanksgiving, he breathed his last breath. Michael Dunn would shoot him to death. Claiming that “he felt threatened” and he “fired his handgun eight times … only after one of the four teenagers in a car threatened him and pointed a shotgun his way,” Dunn hinged his defense on fear and safety—his own.

Yet, according to Davis’ father, “There wasn’t a gun. They were just kids, 17-year-old kids. They have never been in trouble. The kids had no weapon, they had no drugs in the car.” While Davis lost his life, while his friends have been vilified and criminalized in the media, while his family grieves, Dunn is working overtime to construct himself as a victim. While this shooting is yet another that is happening #every36hours involving an African American victim, Dunn’s defense is denying that race matters.

Yet, according to Davis’ father, “There wasn’t a gun. They were just kids, 17-year-old kids. They have never been in trouble. The kids had no weapon, they had no drugs in the car.” While Davis lost his life, while his friends have been vilified and criminalized in the media, while his family grieves, Dunn is working overtime to construct himself as a victim. While this shooting is yet another that is happening #every36hours involving an African American victim, Dunn’s defense is denying that race matters.

Then there is Shelly Frey, who was killed in front of her two children after she ALLEGEDLY stuffed items into her purse. When confronted by a Wal-Mart security guard, Frey, “ran to a car — that had two small children in it — and mashed the accelerator as he attempted to open the door.” In response, he fired one deadly shot into the car, fatally wounding her. Yet, again, claims of fear and suspicion justify the aftermath. Thomas Gilliland, spokesperson for Harris County Sheriff’s Office, offered additional justification noting: “I think it knocked him off balance and, in fear of his life and being ran over, he discharged his weapon at that point.” He added, “He confronted the suspects at the exit of the store before they left. One female wouldn’t stop, struck the deputy with her purse, and ran off.”

And while some will note that the off-duty officer who was moonlighting at a security guard was African American to deny the racial implications, race always matters. In a country where black is suspicious, where the site of a black body compels fear, where stereotypes lead people to see things that aren’t actually happening, to note weapons that are never found, can we ever talk about fear, danger, and suspicion away from race. “The frightening thing, if you are a young African-American man, is that you know nothing makes some folks feel more ‘threatened’ than you,” writes Leonard Pitts. “Nor do you threaten by doing. You threaten by being. You threaten by existing. Such is the invidious result of four centuries of propaganda in which every form of malfeasance, bestiality and criminality is blamed on you.”

The consequences of racism are clear from Jordan Davis to Trayvon Martin and from Rekia Boyd to Shelly Frey. A report from the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement (MXGM) entitled, “Report on Extrajudicial Killings of 110 Black People,” highlights the epidemic of killings, by police, security guards, and others empowered to “protect and serve.” A great number of killings, the police and others have justified shootings with claims of self-defense, fear, suspicion, and alleged weaponry.

- Stephon Watts, a boy with Asperger’s Syndrome was shot and killed after police claimed he “lashed out with a kitchen knife.”

- Justin Sipp lost his life after an off-duty police officer “thought Sipp looked suspicious.” Following a routine “traffic stop for broken tail light” and argument,

- Dante Price was shot 22 times by security guards who claim he tried to run them over with his car.

Sadly there are many more cases – Rekia Boyd, Canard Arnold, and Dakota Bright, just to name a few. To be sure, racism is at the center of each one.

In 2008, 20/20 conducted an experiment to examine how people would respond to criminal activity. Inside a New Jersey park, three white youths gleefully vandalized a car. Without concern for the people walking through the park, they destroyed the car with a bat and spray paint. In the course of the experiment, only a few individuals called the police or even challenged the kids. Some even joked with them. When 20/20 swapped out the three white youth for three black youth, the public response drastically changed. In short, there were many more calls to the police. The interchange between race (and by “race,” I mean black) and criminality produced a host of stereotypes. However, a particular unintended consequence of the experiment was perhaps most telling.

As the white youths wreaked havoc on the car, three black youth waited in another car. These boys, relatives of one of the black actors who were taking part in the experiment, were asleep. In the first instance, the caller suggests that the boys looked like they were going to rob someone. In a case of ‘sleeping while black,’ there were two 911 calls (compared to one 911 call about the white youth). Given persistent stereotypes, the criminalizing narratives of commonplace on the news media and popular culture, it is no wonder that whites saw blacks as criminals irrespective of behavior. “The mainstream media continue to play a role in perpetuating these stereotypes. UCLA professor Travis Dixon’s studies show news portrayals of blacks, as criminal and threatening, have not improved dramatically over the years,” writes Ava Thompson Greenwell. Whatever the outcome of the Martin and Davis cases, African Americans (particularly males) must continue to live with this history. By acknowledging the problem, perhaps one day it will be solved. To do otherwise means more young black bodies remain vulnerable when they do not need to be.

It is no wonder that black bodies elicit fear and animosity given the consequences of a society that consistently dehumanizes blackness.

Writing about research on imagery and criminalization, Joe Feagin, in The White Racial Frame, highlights the profound issues at work here. “These researchers conclude that the visual and verbal dehumanization of black Americans as apelike assist in the process by which some groups become targets of societal ‘cruelty, social degradation, and state-sanctioned violence” (p. 105). From a history of slavery and lynching, up through the persistent realities of racial profiling, mass incarceration, and daily instances of violence, the connection between dehumanization and criminalization has been central to white supremacy.

According Project Implicit, “An analysis of more than 900,000 completed Implicit Association Tests (IAT) at the Project Implicit website suggested that more than 70% of test takers associated White people with good and Black people with bad more strongly than the reverse.” If you think race isn’t important, “Ask yourself why whites who are hooked up to brain scan monitors and then shown subliminal images of black men — too quickly for the conscious mind to even process what it saw — show a dramatic surge of activity in that part of the brain that reacts to fear and anxiety?” (Wise, 2012). Ask yourself about police mistaking a wallet for a gun, or fact that people are more likely to misrecognize a tool “tools” as “guns” when linked to black bodies.

Michelle Alexander, in New Jim Crow, argues that the institutionalization and saturation of mass incarceration created a society in which the “prison label” and the stigma of criminality “exists whether or not one has been formally branded a criminal” within contemporary America: “In this way, the stigma of race has become the stigma of criminality. Throughout the criminal justice system, as well as in our schools and public spaces, young + black is equated with reasonable suspicion, justifying arrest, interrogation, search and detention of thousands of African Americans every year” (p. 194).

Shelly Frey and Jordan Davis are yet more reminders of this reality. From Sean Bell to Oscar Grant, from Emmett Till to Robbie Tolan, from Trayvon Martin to Rekia Boyd, from Amadou Diallo to Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams, who both died after “13 officers unloaded a total of 137 bullets” into their car, these stories have become all too familiar. The excuses, the posturing, the claims of self-defense, the criminalization and demonization have become equally ubiquitous. The dreams deferred and the mourning families have become an everyday or at least an #every36hour reality.

One can only hope, demand, and fight for justice because the killing needs to stop.

This piece builds upon and includes excerpts from a previously published piece at New Black Man.

0 comments