EMERGING FEMINISMS, Disbanding with White Patriarchy, Embracing Ourselves Despite Our Differences

By J.T. Roane

The poison that is white patriarchy, has seduced all. It is like what Black feminist scholar Vivian Gordon called in a different context, sugar-coated arsenic. It may be sweet to many of us, but once swallowed it will kill us just as dead. I use the metaphor of seduction intentionally. Although we might try and deny or disavow it, we are aroused by the virile power of the white phallus-centric culture that is at the heart of American dominance and decadence. We worship the accoutrement that white patriarchal power promises but which is also always fleeting—the unchecked access to material objects, sexual objects, and false comfort in stability. But these “gifts” of white patriarchy will constantly evade us, not only because white patriarchs limit who can drink of fruit of the world’s productive, reproductive, and sexual labor, but because the architectures of a white dominated patriarchy mean to kill us. You, me, her, him, they. We are, even if we identify as straight black men, part of the universe of Man as objects to be consumed and disposed. We continue to worship white dick at our own peril, and at the peril of the majority of the world’s inhabitants, human and otherwise.

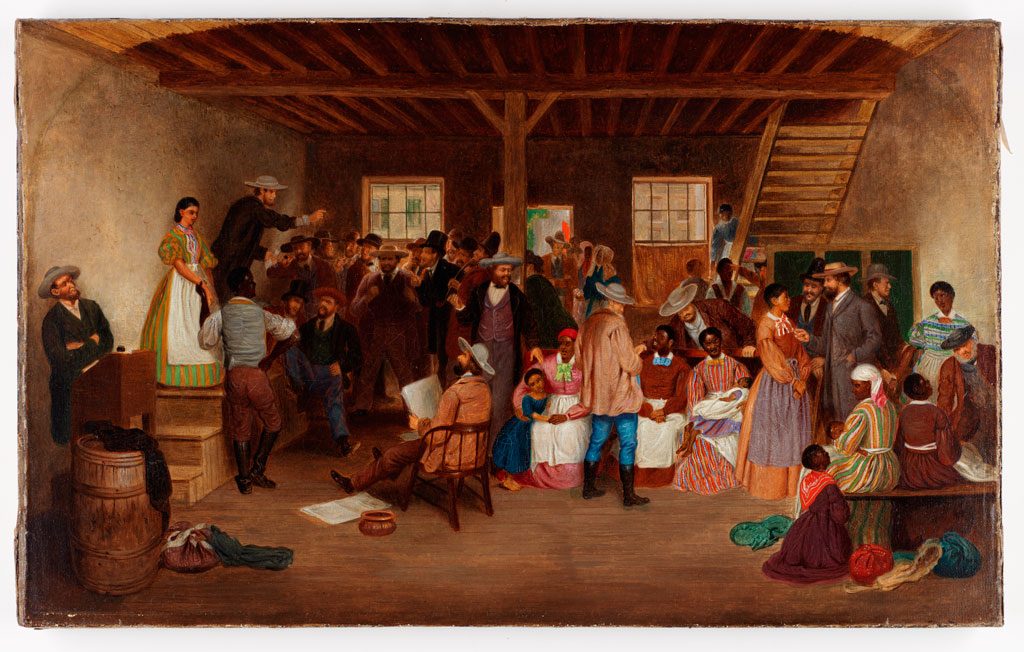

Where did this model of power originate? Largely, as we know it in its modern form, in the hull of the slave ship and on plantations. There we all watched as a model of obscene and over-the top power was crafted through us as its raw material, on land that didn’t/doesn’t belong to any of us. The second sons of the European aristocracy, who could not claim land at home, came here to garner access to land and the luxuries that accompanied it. They renamed the land with feminine metaphors and sought to impregnate it with tobacco, sugar, indigo, rice, cotton at a profit. But it was not theirs. It did not belong to them and so the desire for second rate Europeans to accomplish great wealth and prosperity in line with the lords and monarchs, cost them genocide. The first sin. Next, they could not find a stable source of laborers to actually do the work required for producing profit, so they grafted emergent racialist discourses onto the model of peasant production they inherited and chattel slavery was born. The second sin.

Although they drew on the metaphors of darkness as evil that we can trace at least the medieval period of European history, the enterprise of anti-blackness required more than a static metaphor of black as bad. It required the constant misnaming of our bodies and our practices of kin. It required the flaying of our bodies into flesh—that which is readily available for overwork, pain, torture, rape, premature death. This was particularly acute for black women, who were always burdened with the doubled-meaning of labor—as production in the field and as reproduction of the enslaved labor force (at least in the U.S. context). Crafty as they were, white patriarchs in power repurposed the older Roman legal structure of partus sequitur ventrem—the child’s status follows that of the mother—to violently refashion black women’s bodies beginning in 1662 in Virginia. Even the children white patriarchs fathered with enslaved women, were also their property. Rape committed against black women, by either white masters and overseers or enslaved black men, was in Saidiya Hartman’s words “neither recognized nor punished by law” as it was “simply unimaginable because of purported black lasciviousness.”

This was also particularly violent for those who in modern parlance we would identify as queer, trans, or gender-non-conforming. Despite the absurd notion that there were no queer/gay/gender-nonconforming Africans before colonialism, it is in fact anti-queerness that is among the primary legacies of slavery and colonialism. It was old Victorian-era statutes that newly post-colonial states from the Middle East, to the Caribbean resuscitated at the moment of the post-colonial to claim power vis-à-vis outsiders even as their territorial and economic sovereignty were being undermined by neo-colonial relations. All of the social signifiers of various gender expression, social position, and spiritual power aligned with non-conformity was erased beginning in the hull of the ship, as enslavers sought to truncate various identities into the commoditized and singular “Negro” with attendant gender binary, male and female. This was part of the calculus of rendering people into saleable objects. The compulsory male and female with reproduction as the only mode of acceptable sex was foremost about reproducing a population of docile and muted commodities.

We all have imbibed of this model of power and its legacies and came to view by force of the whip, the horizon of possibility for power as that of the master, with mistress on a pedestal, with everything and everyone under one’s control, here for one’s pleasure. We forward this abusive vision of power when we continue to assume that other people’s bodies should be available when and how we want them; when we share memes that deny the humanity of black women who embrace their sexuality or who support themselves on government aid; when we violently embrace or silently condone the murders of black trans people; when we refuse to march after police kill black girls like Aiyana Stanley Jones or black women like Korryn Gaines; when we remain silent despite relative positions of power and influence. We reinforce white patriarchal power in ways small and large.

Luckily for us, however, black women, black queers, and some straight black men have been consistently practicing the kinds of morality that are dangerous to this order because they create a different kind of futurity and horizon. Dangerous morality signifies a kind of ethical work to upend and obliterate the very structures that bind us to the dominant model of white patriarchal power. The rest of us just need to know that we are here to learn, follow, and work. Our age calls for us to be forwarders of dangerous morality and thus revolutionaries. No, not the kinds of masculinist revolutionaries who don berets and take to the hills as guerillas. That is martyrdom in a place where we don’t control the means of violence. Martyrdom may have a place in future struggles, but ultimately if the revolution isn’t about life, then it’s doomed. Revolutionaries in the sense that we can help to envision and create a new horizon of power.

If, to paraphrase Ruthie Wilson Gilmore, power is the ability to get people to do what they might not otherwise, then power is neutral. This kind of revolutionary power means that we show up and show out when black women and queers are dying eventfully and in the painfully slow ways that result from neglect. It means that we take responsibility for interrupting misogynoir. It means that we refashion masculinity outside of patriarchy. It means that we begin articulating a vision of power that is not bound to destroying the earth itself. It means that we embrace each other across our differences. It means that we practice the world we desperately need in our daily lives and in our intimacies.

J.T. Roane is the McPherson/Eveillard Postdoctoral Fellow and Lecturer in Africana Studies at Smith College. He received his PhD in 2016 from Columbia University in History and is also a 2008 alumnus of the Carter G. Woodson Institute at the University of Virginia. Roane is primarily interested in questions of place in relation to black histories and is currently at work on a manuscript titled “Sovereignty in the City: Black Infrastructures and the Politics of Place in Twentieth Century Philadelphia.” The manuscript charts the history of two very different visions for social affiliation and obligation, black vitality and sanitized citizenship, and the ways they shaped Philadelphia—a primary testing ground for urban policies, sociological and historical inquiry, and social experiments of reform up through the twenty-first century. Specifically, Roane sets modes of alternative land stewardship and governance from Philadelphia’s black working class communities in contrast with the urbicidal practices of reformers who worked to enhance the profitability of the region at the expense of black and working class neighborhoods between 1940 and 1991. Follow him on Twitter @JTRoane.

J.T. Roane is the McPherson/Eveillard Postdoctoral Fellow and Lecturer in Africana Studies at Smith College. He received his PhD in 2016 from Columbia University in History and is also a 2008 alumnus of the Carter G. Woodson Institute at the University of Virginia. Roane is primarily interested in questions of place in relation to black histories and is currently at work on a manuscript titled “Sovereignty in the City: Black Infrastructures and the Politics of Place in Twentieth Century Philadelphia.” The manuscript charts the history of two very different visions for social affiliation and obligation, black vitality and sanitized citizenship, and the ways they shaped Philadelphia—a primary testing ground for urban policies, sociological and historical inquiry, and social experiments of reform up through the twenty-first century. Specifically, Roane sets modes of alternative land stewardship and governance from Philadelphia’s black working class communities in contrast with the urbicidal practices of reformers who worked to enhance the profitability of the region at the expense of black and working class neighborhoods between 1940 and 1991. Follow him on Twitter @JTRoane.

0 comments