June Jordan, Genre Fiction, and Publishing for the People

June Jordan was a gorgeous embodiment of intersections and contradictions throughout her life. 2016 marks my 10th year as her successor as the Director of Poetry for the People in the African American Studies Department at UC Berkeley. And it seems to be this year that I am standing at that crossroads of complexity, figuring out what it means to be “for the People” while working from inside an elite academic institution.

In her memoir, Soldier, Jordan describes her earliest life in the hood—Harlem—and then moving to an upwardly mobile immigrant neighborhood in Brooklyn. While the move did help her escape some of Harlem’s street violence, the relative privacy of their new home exacerbated the domestic violence in her family, namely her father’s ability to target her with physical abuse. The book ends with June heading into Northfield Mount Hermon in Massachusetts, an elite boarding school for girls, where she says she became “completely immersed in a white universe.” Her love for precise and powerful language and writing was inherited from her West Indian father, yet nurtured in boarding school and later at Barnard College. Thus, she has always carried those warring factions within herself: her fierce African diaspora tongue and the colonial language of English to speak with it.

At UC Berkeley, she founded Poetry for the People, an unprecedented program in which the work of student poets was given equal weight with the literary canon. Jordan’s canon was deep and diverse, including poetic voices of all colors from the U.S., as well as the Global South, women, people with disabilities, LGBTQ folks, and beyond. Jordan believed that anyone can write and anyone can teach. She put those beliefs into action and developed tools to elicit powerful poems from student undergraduates and all others who wanted to sit in on her classes. She then trained participants to be the Student Teacher Poet facilitators of the poetry workshops in her accredited, 4-unit, upper division undergraduate course at UC Berkeley. The student teachers not onlly workshop each other’s poetry, but they also assign grades. This peer-to-peer, each-one-teach-one model continues as the foundation of the program to this day. It serves as an antidote to the white- and male-dominated spaces in the academy, the very community Jordan was seeking for herself. Jordan says of her own experience in Poetry for the People: At last, I had become a part of an academic community where you could love school because school did not have to be something apart from, or in denial of, your own life and the multifarious new lives of your heterogeneous students! School could become, in fact, a place where students learned about the world and then resolved, collectively and creatively, to change it!

Jordan could found the program on the faultline between the university and the community and lead it brilliantly because she had managed to embody those class contradictions. She was irreverent, outrageous, at times bawdy and inappropriate. Sometimes she would drink too much around her students; sometimes she would try to matchmake among them. All these activities are inappropriate in an academic setting, but perfectly welcomed in a poor or working class environment. She instructed students from all backgrounds study Black English, with the insistence that the language only lacked legitimacy due to racism. She made students experience the discomfort of language assimilation by assigning them to write blues poems in Ebonics. She managed to create a program that was both Harlem—with all its Black English magnificence—and the elite girls’ school, with rigorous standards for scholarship.

Through Poetry for the People, she built an unprecedented community engagement program within an accredited college class. She upended college hierarchies by consistently valuing the voices and leadership of people from marginalized communities. Yet, I have listened to former student teachers recall how they would obsess anxiously about their poems, striving for ever-higher levels of excellence for fear of disappointing Jordan. Her disapproval and disfavor was to be avoided at all costs. She simultaneously played the role of her young self—straining for freedom. And her father—inspiring fear and demanding that she be a soldier in a war for black excellence.

My students will tell you, I am not one to be feared. I demand far less rigor than she did. We live in economically harsher times—my students have multiple jobs, family home foreclosures, anti-depressant prescriptions. My classroom is more forgiving. But I don’t have to raise soldiers, like she did—poets who would embody the level of academic excellence to justify the fledgeling program. It now stands as an institution—25 years strong—in an era of Cave Canem, Macondo, Kundiman, and VONA. I have nothing to prove in the classroom. The model works. Yet 2016 finds me in my own push-pull moment of exploring what it means to be “for the People” and inhabit that tension between elite institutions and the larger communities they routinely dismiss.

In the early ‘90s after I graduated from Harvard, I knew I wanted to write. I was a member of the Darkroom Writers Collective in Cambridge, and I dreamed of being a novelist. Coming from an elite institution, somehow I felt it was my job to become the next Toni Morrison. She set the standard when she won the Pulitzer in ’88 and the Nobel in ’93 of what black women writers could aspire to. Many of us who had pushed ourselves (or been pushed) into elite institutions now saw ourselves as slackers if we came home with anything less than a Pulitzer. My own writing was a battle between literary and genre fiction, the latter capturing my heart, but leaving me with the sense that I had failed to fulfill my potential somehow. Like, there was a panel of angry white men who would berate me: “We didn’t let you into Harvard so you could write genre fiction!”

But everything about Harvard had been a disorienting process of passing, pretending I knew what everyone else—white or of color—already seemed to know. I was endlessly tasked with unlearning my provincial California ways. Apparently, sophisticated people wrote literary fiction. So be it.

But many years later, my literary fiction could never quite gain traction. A white agent once asked me, her face a mask of disdain, Who do you think is going to read this? Her question was fueled by multiple layers of racism: she couldn’t imagine white people being interested in stories of diasporic black people beyond African American narratives of suffering. She couldn’t imagine people of color as an important audience worth writing for. She couldn’t imagine books centering on groups of black women, who weren’t focused on men. And finally—the only one she probably got right—she couldn’t imagine the white editors in the industry getting on board to publish that type of book.

Years later, I found that my hybrid literary/genre fiction had much more appeal. It could be fueled by the underlying political analysis that I learned in years of activism, as well as my history, political science and women’s studies classes. Yet like all genre fiction, it could run those thematic engines along a time-tested plot track: suspense, intrigue, romance. I was writing the books I wanted to read, but beyond that, I was writing books that I wanted the masses of young women to read.

In my debut novel, Uptown Thief, I became strategic: if today’s audience of young women craves sexy books, then I decided to set my book with sex workers, because sex work is a location that is as inherently politicized as it is sexualized, sitting at the intersection of gender, race, capitalism, and nation.

In my debut novel, Uptown Thief, I became strategic: if today’s audience of young women craves sexy books, then I decided to set my book with sex workers, because sex work is a location that is as inherently politicized as it is sexualized, sitting at the intersection of gender, race, capitalism, and nation.

Uptown Thief comes out in July. I think of it as a wild, feminist experiment in engaging young women’s appetites. Most girls in our country—from their earliest days—are raised on Disney. And what do they learn? Have a sexualized body, but be virginal. Marry a prince. Have lots of money and status. These same themes continue throughout women’s lives in our society. And yet, a counter-narrative shames and blames women for being “stupid” or “shallow” or “vapid.” It devalues all the entertainment for grown women that builds upon those same themes: rom coms, TV shows, romance literature. With Uptown Thief, I began with the following premise: what if I didn’t criticize any of women’s appetites, regardless of the fact that patriarchy might have been central of developing them. What if I decided to engage them non-judgmentally? What if I decided to play with these appetites? Just because the romance genre has traditionally been about the poor girl marrying the billionaire, it doesn’t mean I can’t flip it. What if it’s about the ghetto girl heisting the billionaire and funding her women’s health clinic? What if I can find an anti-classism angle in shopping for designer shoes? What if I can disrupt the gender dynamics in the moment where the heroine swoons over the hunky love interest? Writing the book became an exercise in finding the story and the scenes that would satisfy those tropes and appetites, but also satisfy me as a writer who wants to forward a feminist and social justice agenda.

I was tracked to become the writer of color who might have poor and working class women as the majority of my characters but the minority of my audience. I mean no disrespect to literary fiction, but the majority of readers out there seek entertainment and escape. Yet there’s no reason they can’t have a diverse cast of women that includes various colors, sexualities, abilities, ages, body sizes, gender identities and class backgrounds. There’s no reason they can’t also engage themes of wealth redistribution and feminism, along with hot women, hunky guys, steamy sex, and heart-stopping action.

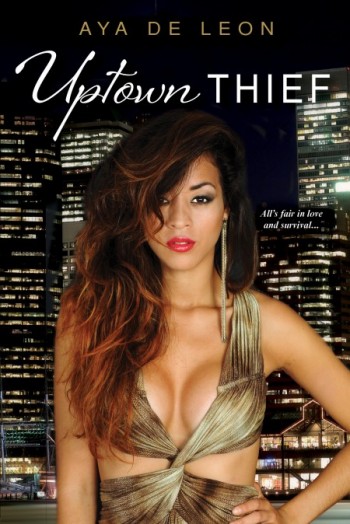

I can’t tell you the number of raised eyebrows when people see my book cover. Kensington’s Dafina imprint always has sexy covers. I like my cover. The amount of cleavage is true to the content of the book, although the breasts are a bit too symmetrical for my usual brand—surgically augmented or perhaps airbrushed. Yet this book is decidedly for the people, in the almost lurid tradition of pulp novels of a bygone era, designed to catch the attention of the masses. At first I felt a bit abashed by the content of the book when talking to academics or other communities that function with a set of middle class values. It’s one thing to study sex work or even romance novels. That bit of distance makes it acceptable. But I generate stories of sex workers, action plots, romantic arcs, ghetto drama. And yet, I have always been an odd fit in academia, because I’m more invested in arts, activism, community transformation and personal growth than I am in “knowledge.”

I always tell people I’m an accidental academic. I teach but I don’t do research. Yet this is my first major experiment in radical fiction for the masses. One of Jordan’s former student teachers told me that prior to June’s death in 2002, there were plans in the works with Alice Walker to create a companion component to Poetry for the People called “Fiction for the Folks.” I don’t think this is exactly what they had in mind. Still, I think of that bawdy, drinking, version of June Jordan, the one laughing loudly and cussing. I can only hope that she would read my book—that Harlem girl, that rowdy New Yorker, and that she would approve.

Aya de Leon is a writer/performer working in poetry, fiction, and hip hop theater. Aya is the Director of June Jordan’s Poetry for the People program, teaching poetry, spoken word, and hip hop at UC Berkeley. Her work has received acclaim in the Village Voice, Washington Post, American Theatre Magazine, and has been featured on Def Poetry, in Essence Magazine, and various anthologies and journals. She was named best discovery in theater for 2004 by the SF Chronicle for “Thieves in the Temple: The Reclaiming of Hip Hop,” a solo show about fighting sexism and commercialism in hip hop. Also in 2004, she received a Goldie Award from the SF Bay Guardian in spoken word for “Thieves” and her subsequent show “Aya de Leon is Running for President.” In 2005, she was voted “Slamminest Poet” in the East Bay Express, and she also co-hosted the kickoff party for Current TV with Mos Def. Aya has been an artist in residence at Stanford University, a Cave Canem poetry fellow, and a slam poetry champion. She publicly married herself in the 90s and since 1995 has been hosting an annual Valentine’s Day show that focuses on self-love. She has released three spoken word CDs, several chapbooks, and a video of “Thieves.” Since becoming a mom in 2009, she has been transitioning from being a touring performer into being a novelist. Aya began blogging in 2011, and since 2013 has been consistently blogging on race, gender and culture. Her recent freelance work has been featured in Guernica, xojane, Huffington Post, The Toast, Ebony, Woman’s Day, Writer’s Digest, Mutha Magazine, Movement Strategy Center, My Brown Baby, The Good Men Project, KQED Pop, Bitch Magazine, The Feminist Wire, Racialicious, and Quartz. She’s on Facebook and Twitter.

Aya de Leon is a writer/performer working in poetry, fiction, and hip hop theater. Aya is the Director of June Jordan’s Poetry for the People program, teaching poetry, spoken word, and hip hop at UC Berkeley. Her work has received acclaim in the Village Voice, Washington Post, American Theatre Magazine, and has been featured on Def Poetry, in Essence Magazine, and various anthologies and journals. She was named best discovery in theater for 2004 by the SF Chronicle for “Thieves in the Temple: The Reclaiming of Hip Hop,” a solo show about fighting sexism and commercialism in hip hop. Also in 2004, she received a Goldie Award from the SF Bay Guardian in spoken word for “Thieves” and her subsequent show “Aya de Leon is Running for President.” In 2005, she was voted “Slamminest Poet” in the East Bay Express, and she also co-hosted the kickoff party for Current TV with Mos Def. Aya has been an artist in residence at Stanford University, a Cave Canem poetry fellow, and a slam poetry champion. She publicly married herself in the 90s and since 1995 has been hosting an annual Valentine’s Day show that focuses on self-love. She has released three spoken word CDs, several chapbooks, and a video of “Thieves.” Since becoming a mom in 2009, she has been transitioning from being a touring performer into being a novelist. Aya began blogging in 2011, and since 2013 has been consistently blogging on race, gender and culture. Her recent freelance work has been featured in Guernica, xojane, Huffington Post, The Toast, Ebony, Woman’s Day, Writer’s Digest, Mutha Magazine, Movement Strategy Center, My Brown Baby, The Good Men Project, KQED Pop, Bitch Magazine, The Feminist Wire, Racialicious, and Quartz. She’s on Facebook and Twitter.

Pingback: "Naming Our Destiny": Afterword to The Feminist Wire's Forum on June Jordan - The Feminist Wire