On Feeling Depleted: Naming, Confronting, and Surviving Oppression in the Academy

By Nicole Nguyen and R. Tina Catania

“There is a politics to exhaustion. Feeling depleted can be a measure of just what we are up against.”[1]

Meet Stuart. He’s a fellow doctoral student. Watching Stuart – a white, able-bodied, middle-class man – for a short time, one sees the ease with which he glides through the academy’s hallways. Stuart pops into professors’ offices and tosses around passages from Das Kapital he learned while attending an elite, private high school. Stuart knows, intimately, how to navigate the academy. More importantly, Stuart can move through the academy, meeting few, if any, obstacles along the way. As Stuart earns the accolades bestowed upon him by other white, able-bodied, academic men – the gatekeepers – we are reminded that social privilege is “an energy saving device” and so “no wonder that not to inherit privilege can be so trying,” especially in the U.S. academy.[2]

Supported by his family, Stuart spends summer days at the beach writing without struggling to survive on his meager stipend. After class, Stuart drives to the home he owns to write journal articles, free from the weight and violence that non-dominant students must often process and endure in the face of unrelenting microaggressions[3] before beginning their own work. Stuart doesn’t need to think about how to make his work intelligible or valued as “real” scholarship.[4] He is not invested in excavating personal stories and organizing for social change with/in communities.[5] Scholars never attack his research, conducted from the confines of his middle-class home and removed from the struggles of everyday life facing oppressed people worldwide, as “personal,” “too sensitive,” or “lacking theoretical heft.”

When Stuart arrives, his peers (and professors) read him as an intellectual. Meanwhile women, students of color, and students with disabilities struggle to prove they deserve a place in the academy. Occupying dominant social locations, Stuart dominates classrooms. In fact, like the white men (and women) who advise him, Stuart interrupts women graduate students in class, looks out the window when students of color speak, and fully ignores the contributions of students with disabilities. During one class, Stuart claimed that “queers shouldn’t have children,” a comment obfuscated by multi-syllabic words and a questionable interpretation of queer theory. Protected by the cover of theory, Stuart’s comment went uncontested and unnamed while its harm quietly seeped into the psyches of queer students and allies. While some depleted students wished to challenge Stuart, they also knew that faculty eagerly supported him and quickly condoned his inflictions of harm. This is how those in power maintain institutionalized oppression even as Stuart and others imagine themselves as radical activists, ignoring the ways they enact and extend the norms they seek to oppose. For Stuart, practice and theory never need to align.

When Stuart arrives, his peers (and professors) read him as an intellectual. Meanwhile women, students of color, and students with disabilities struggle to prove they deserve a place in the academy. Occupying dominant social locations, Stuart dominates classrooms. In fact, like the white men (and women) who advise him, Stuart interrupts women graduate students in class, looks out the window when students of color speak, and fully ignores the contributions of students with disabilities. During one class, Stuart claimed that “queers shouldn’t have children,” a comment obfuscated by multi-syllabic words and a questionable interpretation of queer theory. Protected by the cover of theory, Stuart’s comment went uncontested and unnamed while its harm quietly seeped into the psyches of queer students and allies. While some depleted students wished to challenge Stuart, they also knew that faculty eagerly supported him and quickly condoned his inflictions of harm. This is how those in power maintain institutionalized oppression even as Stuart and others imagine themselves as radical activists, ignoring the ways they enact and extend the norms they seek to oppose. For Stuart, practice and theory never need to align.

The academy wasn’t just built by people who look like Stuart. It was built with his body in mind. Stuart doesn’t have to worry about how he will get in/to his classrooms. He just shows up, opens the door, and walks right in. Stuart doesn’t have to make endless calls to Disability Services, Parking Services, Dean’s Offices, and the like, just to secure a disabled parking permit to be near his classroom. He doesn’t have to think about getting up that hill. About the potential un-shoveled sidewalks and streets. About the ice and slush that jam in a wheelchair’s tires.

Stuart isn’t watched or marked. He doesn’t have to hear the whispers about his use of the “Handicap” button to open doors. Doors that are too heavy for this body. He doesn’t have to carry a cooler of food and medicine to class and with him at all times to regulate his blood sugar. He doesn’t have to spend days making special food so that he’ll have enough for the school week. For class, for unexpected meetings on campus. He can spend time reading Marx for fun because his body doesn’t require the amount of work or time that this body does.

People like Stuart can glide through academia not thinking about the ways the buildings they use, the classrooms they occupy, and the events they attend exclude certain bodies. Stuart’s body doesn’t just not experience battle fatigue because of dis/ability, or race, or class, or sex, or gender; Stuart’s body doesn’t get physically fatigued. Because for him a door is not an obstacle. Finding a gender-neutral and accessible bathroom is not an obstacle. Getting to campus is not an obstacle. Leaving the house is not an obstacle. Using a computer is not an obstacle. People like Stuart are not tired of fighting because they don’t have to fight for their bodies to exist in the spaces of academia.

The echoes of praise about Stuart’s productivity issued by faculty members sting. Their reverberations act as a constant reminder of who the academy values and whose knowledges count. Stuart doesn’t have to think about how to make his body read as smart, as academic, as belonging; smartness is already mapped onto his white, male, able-bodied self. Stuart, thus, embodies the white supremacist, capitalist, colonial, ableist, and gendered privilege coursing through everyday life in the academy. He represents how power and privilege shape the graduate school experience. This story, then, is not about Stuart qua Stuart: it is about how we, non-dominant students, encounter, negotiate, and confront structures of oppression within the academy.

Yet, in the telling of Stuart’s violence, we do not seek to center his actions. Rather, we begin with these stories to place the body, our bodies, within the colonial, ableist, patriarchal, white supremacist academy. Such stories purposefully sketch how privileged bodies effortlessly move through graduate school while the academy “wears” on those “who do not quite inhabit the norms of the institution.”[6]

We write, together, to name this institutionalized violence so endemic to the academy.

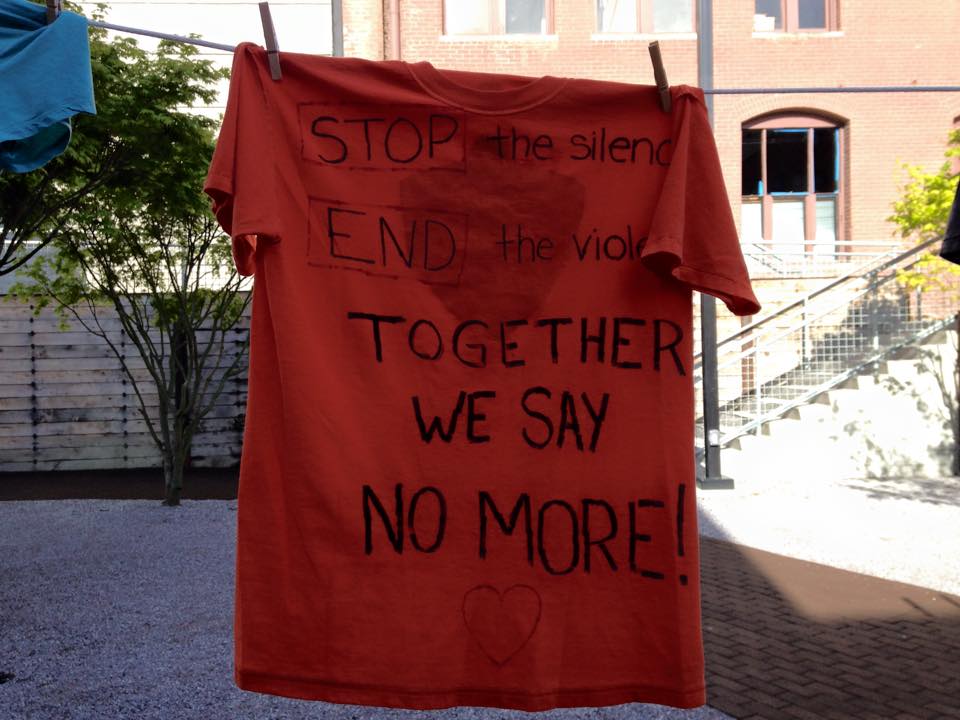

We write because we cannot remain silent. And the “we” that we envision is more than our own impulses. It is a collective we that cannot be and will not be silent in the face of oppression. As Audre Lorde writes, “Your silence will not protect you.” The silence[7] of individuals who are “waiting to get a job” or “waiting to get tenure” or “keeping their heads down and doing their own thing” does not protect them from microaggressions, from oppression, from depletion.[8] What it does do is continue to reify and entrench the oppressive nature of the academy; it disciplines us to stay silent, to reinforce oppression, and to participate in its reproduction.

Thus, we urge every-body, but especially those in positions of power (i.e., tenure-track and tenured faculty) to name oppression. To name sexism. To name ableism. To name racism. To be cognizant of how these -isms intersect to violently oppress and privilege particular bodies and identities.

We must name instances, call attention to the ways that the academy’s daily practices are multiply oppressive. And we should do so whether we experience them through someone like Stuart, a prototypical, privileged, white male, or through anyone else whether white feminists, able-bodied people of color, or male “allies.” These violences, from whomever they come and through whatever structures make such encounters possible, must be named. They must be resisted. And they must be transformed.

We recognize that, as Sara Ahmed warns, “exposing a problem is to become a problem.”[9] Yet, we refuse to be disciplined. We refuse to have our words, actions, and experiences foreclosed for fear of being read as the “problem,” always “stirring up trouble.” Fuck the fear that the discipline, field, department, administration, university, society tries to instill in us so that we do not speak up, so that we do not name our oppressions. We recognize the academic institution and its practices for what they are: inherently oppressive. We recognize that many have no desire to critique the academy because they do not want to jeopardize their privilege within it. We recognize that critiques of academia are necessarily limited by those who make them when they are invested in maintaining its structure, a structure that works for them.

We seek to radically reshape and remake the institution in more equitable ways. True solidarity cannot pay lip service to feminist, de-colonial, anti-racist projects while maintaining individual investments in a system that works for only the most privileged bodies. Marginalized individuals cannot but participate in the oppression of other marginalized people if they are invested in academia’s current structure. Increased “representation” merely reifies the system rather than expands the possibilities for solidarity, for change.

We see our colleagues, our cohorts, our faculty, our peers, and even ourselves as colluding in these oppressions when they (we) ignore them, when they ignore us, when they remain silent at their occurrence, when they are oblivious to their daily repetition. When your colleague does not plan an accessible, inclusive event from the beginning, they actively reproduce ableism and create exclusionary spaces. And our naming that problem, and therefore your collusion in ableist oppression, makes us the problem, rather than you or the institution. When the violent actions of white, male students not only go unpunished, but undiscussed and unrecognized by faculty, you actively participate in our racialized and gendered oppression.

Within a deeply inequitable institution, we strive to navigate a space for ourselves, for understanding. We understand that we are a part of the academy and that our actions can also work to sustain it. Yet we strive for a different academy. We seek to transform the institution. For us, this includes naming the violences of those like Stuart and rejecting the common call to discipline ourselves into not writing or voicing radical critiques of the academy.

So we begin here, with a naming of sorts. We write to name what we should not name.

Yet writing also serves as a way to carve out alternative spaces. Spaces that contribute to our survivability and to our resistance against these structural and everyday forms of oppression. These spaces are where we “recognize each other, find each other, create spaces of relief, spaces that might be breathing spaces, spaces in which we can be inventive.”[10]

We write together to claim our intersectional identities and recognize that for us, the academy must include the stories of our bodies, our exclusions, our resistances, our politics, our activism. We write to document our exhaustion in surviving, resisting, and reshaping this deeply violent institution even as we, as graduate students, occupy particularly precarious positions. Given these oppressions in the academy, this is a call for different, transnational, cross-border, and accessible forms of solidarity.

We write, ultimately, as an invitation to those other depleted-yet-vibrant bodies, bodies who imagine another kind of academy. An academy that is collaborative, feminist, and inclusive. It is an invitation to strategize, to survive, to heal.

Notes

[1] Ahmed, S. (2013). Feeling depleted? feminist killjoys. Retrieved December 13, 2013, from http://feministkilljoys.com/2013/11/17/feeling-depleted/

[2] ibid, para. 8

[3] Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.

[4] Ellison, J., & Eatman, T. K. (2008). Scholarship in public: Knowledge creation and tenure policy in the engaged university.

[5] Sudbury, J., & Okazawa-Rey, M. (2009). Introduction: Activist scholarship and the neoliberal university after 9/11. In J. Sudbury & M. Okazawa-Rey (Eds.), Activist scholarship: Antiracism, feminism, and social change (pp. 1–16). Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

[6] Ahmed, S. (2013). Feeling depleted? feminist killjoys. Retrieved December 13, 2013, from http://feministkilljoys.com/2013/11/17/feeling-depleted/, para. 3.

[7] We acknowledge that silence can be used as an ableist term to disparage other forms of communication. We recognize, however, that communication occurs in many ways including the nonverbal and that language is always already an imperfect representation. Here, when we refer to silence, we mean the refusal to name oppression.

[8] Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outsider. Trumansberg: Crossing Press.

[9] Ahmed, S. (2014). The problem of perception. feminist killjoys. Retrieved July 12, 2014, from http://feministkilljoys.com/2014/02/17/the-problem-of-perception/, para. 1

[10] Ahmed, S. (2013). Feeling depleted? feminist killjoys. Retrieved December 13, 2013, from http://feministkilljoys.com/2013/11/17/feeling-depleted/, para. 13.

_____________________________________

Nicole Nguyen is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in Educational Policy Studies at the University of Illinois-Chicago. Her research interests include national security and U.S. public schooling, participatory action research, ethnography, and feminist geography.

Nicole Nguyen is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in Educational Policy Studies at the University of Illinois-Chicago. Her research interests include national security and U.S. public schooling, participatory action research, ethnography, and feminist geography.

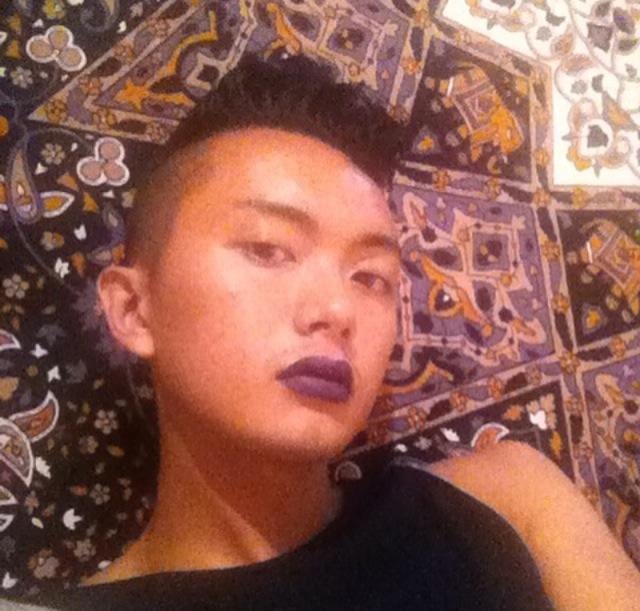

R. Tina Catania is a Ph.D. student in Geography at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University, where she also obtained a Certificate of Advanced Studies in Women’s and Gender Studies. Her research interests lie at the intersections of immigration, identity, human rights, borders, feminist theory and practice, and auto/ethnography. She has conducted fieldwork in the United States in several locations—including California, Louisiana, and Texas—and in Italy—Lampedusa, Sicily, and Rome.

Pingback: On Feeling Depleted: Naming, Confronting, and Surviving Oppression in the Academy – The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire | MiscEtcetera v2

Pingback: DAILY DISPATCHES 08/06/14 | Fayetteville Free Zone

Pingback: On the non-sense of an abstracted higher education | Richard Hall's Space

Pingback: Links: 08/08/14 — The Radish.