EMERGING FEMINISMS, @catcallsofnyc

By Sophie Sandberg

I’ve always liked dressing in a “feminine” way. I love sundresses, low cut shirts, short skirts. I like how these clothes look on me. I feel comfortable wearing them. This is my style and one way I express myself. Unfortunately, I’ve learned from a young age that some men take a skirt, dress, or cleavage as an invitation to catcall. I began to realize this at fifteen. It was summer. I had a job at a bakery in downtown New York City. I was excited– about the job– but mostly about how I would dress for it. I loved getting dressed up and this was an opportunity to show off my style in a “real world” setting.

This was one of the first times I had to walk somewhere alone. I would walk short distances before: back and forth to friends’ houses, to the bus. But I was never dressed up. This walk from the 14th street #1 train stop to 18th street and 10th avenue was my first independent walking experience… and my introduction to catcalling.

I don’t remember the comment that took my catcalling virginity. It could have been a mumbled “Hey Gorgeous,” a breathy declaration of “Beautiful,” a kiss-y sound, or “mmm” noise as I passed by. I remember those blocks– every variation of how I walked them. That square, 14th to 18th long and 7th to 10th wide, is etched in my memory with each comment. Every man I passed was a road block, an obstacle, and potential cat-caller. As I walked down long avenues, I saw them from afar and thought, “Don’t say something to me. Please, don’t talk to me.” I fidgeted as they looked at me. It didn’t matter whether they catcalled me because the long walk towards them made me painfully self-conscious either way. And so many of them did say something.

I was embarrassed in my lavender dress and espadrille wedges; an outfit I decided was perfect before leaving the house. It felt wrong to ignore them, I felt like I should smile politely or say thank you. When it kept happening, I was concerned my dress was too low-cut or short and inappropriate for work. When I got home that day, my dad suggested that maybe I should dress down so I wouldn’t have to deal with this. This is one reason catcalling makes me so angry. I’m forced to feel unsafe when I wear the clothing I like. I shouldn’t change what I wear to be catcalled less. But I don’t want to be catcalled because it makes me feel uncomfortable, under surveillance, undressed by eyes of strangers.

This twisted practice didn’t come from thin air. Historically, the only women in public were prostitutes. Elizabeth Alice Clement (2006) explains, “Nineteenth- century notions of the meaning of ‘public’ easily, and perhaps deliberately, conflated ‘women in public’ with ‘public women,’ or prostitutes” (47). It wasn’t until 1900 that women “went to work outside their homes”(50). With the presence of the new “working woman” it became “impractical for most observers to automatically associate women in public with prostitutes” (50).

This may seem like a step forward for women, however, it was with their entrance into the public realm that catcalling and other sexist behavior became a “public” problem. According to Holly Kearl (2015) “during the 1970s and early 1980s … newspapers routinely printed the commuting schedules and physical measurements of pretty women who worked on Wall Street, and some men lined up outside their work places to harass them” (xiv-xv). Talk about putting women under surveillance! Although perhaps less drastic, this historic and public surveillance of women continues everyday with catcalling.

And five years from my initial experience, the threat of catcalling renders me helpless. No stranger to it now, I’m still taken aback with each comment. I know what I want to do — flip them off, yell, get angry— but without fail, I freeze.

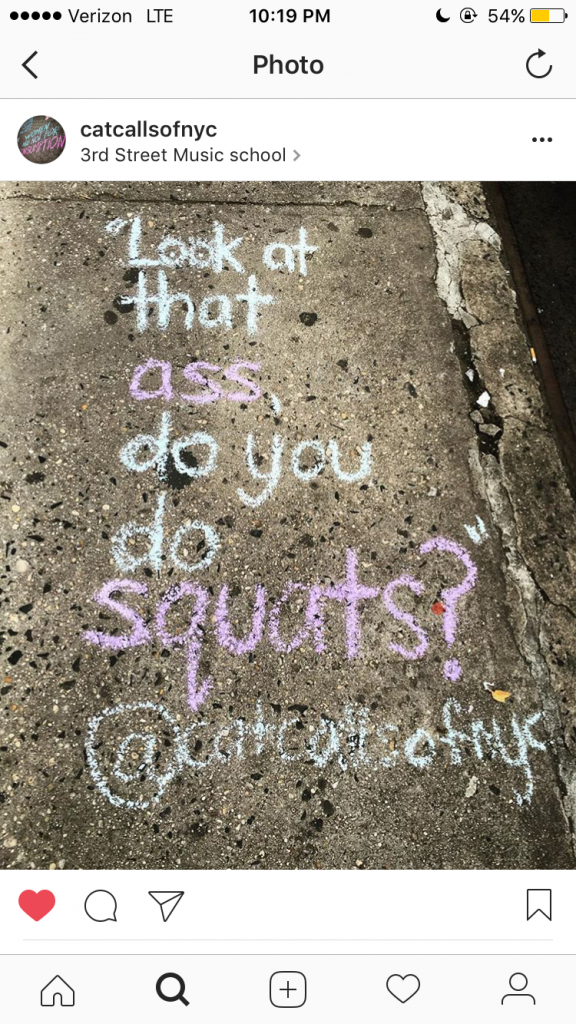

So, I set out to do something. I couldn’t stop catcalling overnight, but by focusing on the catcalls themselves I could be an agent. I could start collecting them from friends, writing them with colorful chalk on the sidewalk where they happened, and posting their pictures on Instagram. I could publicize the words with which men force women to be passive objects. By revealing the language used to catcall women, I could get in peoples’ faces. I could provoke shock, disgust, confusion, anger. So many catcalls are hidden from the public: mumbled on deserted streets and whispered in the dark. I wanted to bring these words to light and reclaim the space. “This is a spot where a woman was catcalled!” The chalk marks would be temporary, washed away in a few days. But the pictures on Instagram, @catcallsofnyc, would grow into a collection and become part of the greater movement to #stopstreetharassment. @catcallsofnyc would illustrate the catcall spectrum, including everything from supposed compliments, “Hey, Beautiful,” to derogatory harassment, “Ok, walk past me fucking ho.”

Day One:

I head back to 11th street between 3rd and 2nd avenue: the spot where a man had rolled down his car window, watched me walk past and “complimented” my “ass.” Chalk in hand, I feel like I can expose him for what he said. I look at the cars and feel like one window might spontaneously roll down. A woman behind me approaches. I look sketchy loitering, and my nervousness makes me feel even more suspicious. Why do I feel like I’m doing something wrong? I find a stoop and sit down. People on a neighboring stoop are chatting. I worry they’ll see me and ask what I’m doing. I worry that if they don’t ask, they won’t understand. My mind starts to run. Is this even allowed? Will I get in trouble? Is this vandalism? Private property? Is there a law against writing curse words on the sidewalk? Right then, an old women comes up to me and says “excuse me.” I’m sitting on her stoop. I jump up, apologize, and leave immediately. I can’t do this right now. I cannot write the word “ass” on the sidewalk. I don’t curse. I babysit. There’s a children’s music school down the block. What if they see it? I picture parents steering their children away from it, shielding their children’s eyes, shaking their heads.

So this isn’t the first one I write down, like I’d hoped it would be. But eventually (after finding a friend for moral support) I write it down. And it feels good. There were parents and kids walking by, which was problematic because the kids– being kids– were very interested in the chalk. But I persevered and tried not to make guilty eye contact with the parents.

Day Five:

My friend Raina greets me, exasperated in high heels, leather crop top, and jeans: “I have a catcall for you! I was groped!” She continues to tell me that a man called out, “Come here, baby” and grabbed her arm after she ignored him. She had to free herself from his grip. Luckily being in a group usually precludes this type of physical harassment, but it seems to encourage extensive verbal harassment. The same night, my friends and I are catcalled by different groups of men. When this happens, I feel a strange sense of power. Little do they know the world will soon see what they said. As they degrade us, I write down their words. 1. “Okay ladies! Fuck it up” (4th avenue, between 10th and 11th); 2. “Yes ladies move that!” (11th between 3rd and 4th avenue); 3. “Ooo look at those short skirts! Let me finger fuck that pussy!” (Lafayette and Canal); 4. “You’re glowing beautiful! Oh ok, walk away like you mean it! We’re just trying to compliment you” (Lafayette and White). In these moments, any sense of power is false. We are afraid. We pick up our pace and focus our eyes straight ahead.

According to psychologist Tracy Lynn Lord (2009), “gender based street harassment” is due to “cultural gender norms.” Men are socialized “to be aggressive and dominant and women [are] socialized to be more fearful and submissive” (2). This manifests itself in public places because, “men view the public domain as their territory, and they harass to maintain their power” (2). Of course, most men who catcall would not admit this as the reason. Most catcallers would say they are simply giving a woman a compliment. This leads to a very problematic conversation. One that assumes any woman should be thankful that her body is being commented upon. She should be thankful to be an object of the male gaze. That simply by walking down the street, a woman should expect her body to be looked at, and if she doesn’t respond to unwarranted comments, she is “rude,” “ugly,” or a “bitch.” Her body and sexuality are always open for male consumption simply because she is a woman.

On 28 August 2014 a Fox News segment covered catcalling and a MediaMatters article accused the hosts of “downplaying the harmful impact widespread street harassment has on women.” Not only do they downplay it, but worse, they reaffirm that men should focus on a woman’s appearance. For instance, the female newscaster states, “Let men be men. God bless them. I love ‘em.” She suggests that men are allowed and expected to do this. Rewarded for it, even. This “let men be men” rationale is victim blaming. We know the story: “She was drunk. She was wearing something sexy. He was tempted by her short skirt, overtaken with sexual desire, no time for consent.” Suggesting the nature of men is to sexualize women condones this violent behavior. It casts women as the problem because they render men helpless against temptation. Society too often feeds into this type of victim blaming. Her every move is questioned while his actions are understood as natural impulse. We remove the blame from the perpetrator and place it on the victim-survivor. I find it disturbing when women, such as the Fox newscaster excuse men at other women’s expense.

As I continue to write down catcalls, I get the sinking feeling that a lot of people are misinterpreting them. One women tagged me in an ‘artsy’ picture on Instagram of her feet in front of a catcall I wrote with the caption “Hump Day Smiles.” Not sure what she thought the catcall “Hey Baby, Where you going?” was supposed to mean. While writing, “Hey Beautiful… awww don’t ignore me,” a man approached me from behind, read what it said so far and said “Hey Beautiful! Yea! I know what you mean… Damn!” Another man asked me for my number as I tried to explain the project to him.

I have spent hours walking around Manhattan, getting down on my hands and knees on the sidewalk, and I know my message often goes unheard. But I keep going. I keep going because I don’t want any young girl to wonder if that uncomfortable moment of being told she is beautiful by an older man on the street is a compliment or if it requires a thank you. Our worth is not measured by these objectifying comments. We have a voice even if that moment silences us, turning us into legs, breasts, ass, hair color. A mundane daily occurrence, we brush it off our shoulders.

We’re desensitized.

We keep walking.

We grow to expect it.

It’s no big deal but slowly it chips away at us. Diminishes us. Reinforces the devaluation of women. @catcallofnyc continues because what is mundane should be rare. Because what desensitizes should outrage. Because we should walk with a sense of safety and respect. @catcallsofnyc continues because I want girls to grow up with different expectations.

Sophie Sandberg is a sophomore at New York University majoring in Social Cultural Analysis. She has a particular interest in the politics of women’s fashion, sexual assault on college campus, and the intricacies of street harassment. In her free time she enjoys knitting, sewing, fashion design, and using visual arts as a vehicle for activism.

Sophie Sandberg is a sophomore at New York University majoring in Social Cultural Analysis. She has a particular interest in the politics of women’s fashion, sexual assault on college campus, and the intricacies of street harassment. In her free time she enjoys knitting, sewing, fashion design, and using visual arts as a vehicle for activism.

0 comments