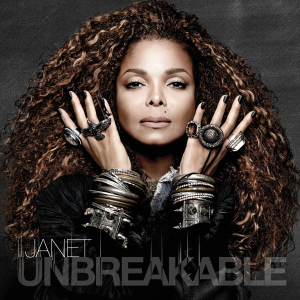

A Review: Son of Baldwin Shares Why Janet Jackson’s Newest Album Reveals She is Unbreakable

In the 2011 BBC Janet Jackson documentary Taking Control, legendary musician/producer/songwriter Jimmy Jam recalls a moment during the recording of Jackson’s Damita Jo album when Janet says to Jam’s musical partner Terry Lewis, “You know what Terry? You write the lyrics. I don’t really feel like I have anything to talk about.” Jam’s response to that was, “Then we shouldn’t be making an album.”

But they did make an album and it was the first since Janet’s 1986 breakthrough Control that didn’t reach the top spot on the Billboard charts. That knock was a revelation. What it revealed was the fact — despite what naysayers might have imagined — Janet was an integral part of her own success, and that her active participation, and, more importantly, her singular focus and evolving creativity was a mandatory part of the equation.

Janet would, however, go on to release two more albums—2006’s 20 Y.O. and 2008’s Discipline—without having heeded that lesson. And the proof is how neither left much of an impression despite a few moderately successful singles. But Janet’s found her voice again on her latest release, Unbreakable.

It’s her most introspective, thoughtful, conscious, and daring effort since 1997’s The Velvet Rope, and perhaps her wisest. Sonically, Unbreakable doesn’t sound like any other Janet album. To begin, Janet’s singing is centralized in a way that it has never been before. It’s a more confident vocal performance where Janet often sings in full voice, as much from the diaphragm as from the head, as much from the heart as from the mind. And she’s never sounded better.

The musical styles are all over the map: There’s some soul and some rock & roll; there’s some club and some Brazilian jazz; and yet the whole thing still manages to feel cohesive. And the balance is striking. And despite an occasional misstep (like the rather generic “2 B Loved”), there’s a great deal to revel in here.

The title track, a song reminiscent of the Jackson Five’s “Never Can Say Goodbye,” is as soulful as we’ve ever heard Janet. It’s an ode to those who have stood by her through her ups and downs, trials and tribulations — whether that be family, friend, or fan. The energetic funk-jam “BURNITUP!” features Missy Elliot, who whoops and hollers and backs Janet up vocally. There’s the hip-hop influenced “Dammn Baby” with its pulsating bassline; her lush self-harmonies are the stars on the gorgeous, dreamy “Night” (which pays homage to Prince’s “I Wanna Be Your Lover”).

The title track, a song reminiscent of the Jackson Five’s “Never Can Say Goodbye,” is as soulful as we’ve ever heard Janet. It’s an ode to those who have stood by her through her ups and downs, trials and tribulations — whether that be family, friend, or fan. The energetic funk-jam “BURNITUP!” features Missy Elliot, who whoops and hollers and backs Janet up vocally. There’s the hip-hop influenced “Dammn Baby” with its pulsating bassline; her lush self-harmonies are the stars on the gorgeous, dreamy “Night” (which pays homage to Prince’s “I Wanna Be Your Lover”).

“The Great Forever” is her own version of brother Michael’s “Leave Me Alone” (she directly tributes Michael on “Broken Hearts Heal,” a song that eventually chugs along like his “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough,” but with far less verve). A haunting ballad, “After You Fall” is dark and reflective, featuring Janet’s soft voice against sparse piano. “No Sleeep” (featuring rapper J. Cole)—a sultry mid-tempo, neo-soul-inflected piece—is the closest we get to bedroom antics, which remain tucked away, playfully, in innuendo. The sweet, swirling (and much too short) retro-R&B gem “Dream Maker/Euphoria” is a standout. It contains a sample from the Jackson Five and it’s where it’s clear that the strength of Janet’s voice, like Mary J. Blige’s, is in its ability to convey emotion.

The album’s pinnacle, however, is the brilliant “Black Eagle,” an evocative, spiritual down-tempo joint that can be read generally as a salve for marginalized peoples generally, or as a shield for black people specifically. It starts with simple finger snaps and twinkling keyboards and Janet’s voice floating over them almost like a lullaby as she uses the metaphor of this bird to talk about the history, contributions, and divinity of a people. But when the bass drops, and she croons “I’m singing this love song to show my support/To the beautiful people who have been ignored”: It. Is. Over. Bliss sounds like this.

On the surprising “Gon’ B Alright,” Janet channels a little Mavis Staples, a little Sly Stone, and a little Tina Turner for an uplifting 60’s jaunt that displays her optimism for humankind’s potential to solve its problems. But that doesn’t mean that the album is letting us off the hook so easy.

The most biting indictment of the status quo comes on “Shoulda Known Better,” whose last line (“I had this great epiphany/And Rhythm Nation was the dream/I guess next time I’ll know better”) is sharp in both its simplicity and implications. Is Janet saying that her old fantasy of a race-neutral, harmonious society was naïve given Ferguson and Baltimore, in view of the corpses of Trayvon Martin and Sandra Bland? It sounds like it. And in that, she offers a necessary radicalism that not many other artists at her level of influence can contemplate much less articulate. And that may be because Janet, herself, recognizes that despite her fame and fortune, in spite of her acclaim and access, her race and gender mark her as among the most vulnerable to state and other kinds of violence. “Lessons Learned,” a song about domestic violence, makes that clear. She’s telling us, in no uncertain terms, that she stays woke.

Unbreakable embodies the kind of fearlessness that comes with wisdom, which leads to liberation. Perhaps when you own your own record label, as Janet does with Rhythm Nation Records, you’re no longer required to bow to the corporate interests that wish to muffle your messages and render you as inoffensive and ineffectual as possible in an effort to appeal to the widest audience and the lowest imagination. This, they believe, ensures the largest sums of money. Well, Janet’s been there and done that. She knows there’s a price to be paid in the rigid system that turns people into commodities at their own expense. And she knows how quickly that audience can turn on you once you’ve exhibited any sign of autonomy. So with this latest project, she took a risk, however calculated. After nearly 40 years in show business, she knows that her strengths, talents, and triumphs lie in her ability to innovate.

And she’s able to do that freely, on her own terms, now that she’s actually, finally, literally in control.

Grade: A.

Robert Jones, Jr. is a writer, editor, comic book, film, music, and TV lover from Brooklyn, N.Y. He is the creator, curator, moderator, and writer for the social justice/social media brand, Son of Baldwin. His writings can be found in The New York Times, The Middle Spaces, Those People, and Mused. He is currently working on his first novel. He can be found on Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter.

Robert Jones, Jr. is a writer, editor, comic book, film, music, and TV lover from Brooklyn, N.Y. He is the creator, curator, moderator, and writer for the social justice/social media brand, Son of Baldwin. His writings can be found in The New York Times, The Middle Spaces, Those People, and Mused. He is currently working on his first novel. He can be found on Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter.

2 Comments