Burying Our Babies: Letter from Los Angeles to Ferguson

In South Los Angeles’s Crenshaw District, there are three funeral homes within a one mile radius of each other. On bright sunny days, young people pour out from their doors after viewing hours, lingering on the steps reminiscing, sporting t-shirts with pictures and art work commemorating the dead. On a thoroughfare that epitomizes L.A.’s deification of the car, cars are often rolling R.I.P. memorials of the dearly departed, the tragedy of stolen youth ornately inscribed on rear windows for the world to see.

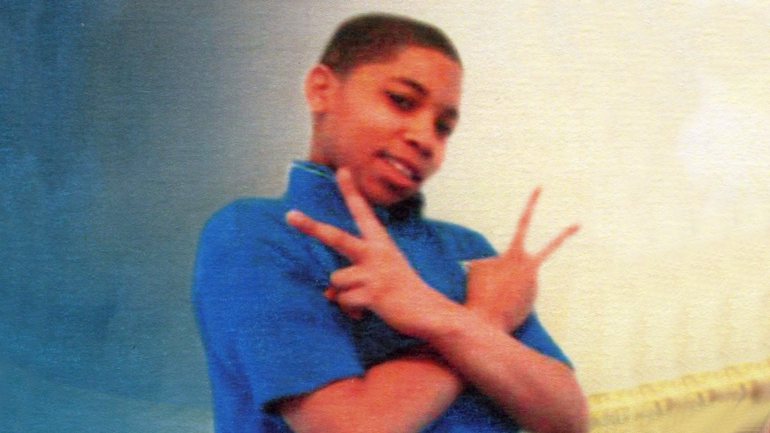

Death is intimately woven into the experience of being a black child in America. The regime of “Black death,” as rapper Chuck D once described it, has its roots in slavery and the violent occupation of black bodies for profit and control. When Michael Brown’s family buries their precious baby today, it will be yet another reminder that the sacrosanct space of childhood is a white supremacist fantasy. As part of the legacy of the 1992 Los Angeles uprising, the Ferguson, Missouri uprising has seared this into black peoples’ consciousness anew.

Teaching in South L.A., the trauma of constant death, loss, and mourning shapes many of my students’ lives. Their oral and written stories are replete with it. When they speak of terrorism, using other language, it has an American face. Last year, when my Black Skeptics Los Angeles organization awarded five South L.A. youth of color First in the Family scholarships, the world was awaiting the verdict in the Trayvon Martin murder trial. Saluting our new scholars this year we mourned the executions of Brown, Ezell Ford, and Renisha McBride, young people who will never have the opportunity to go to college, have a career, or pursue their life’s dreams. At the end of the semester at one school I work at, I was shown a list of college-bound students that had no black male names on it. It was a short list to begin with, a mere forty students out of three hundred, the majority first generation Latino graduates. That same day, yet another black boy is led off campus in handcuffs by the school police. A few minutes later, I meet with the Young Male Scholars group, brilliant ninth and tenth grade black boys who are becoming politicized about the fact that the curriculum does not represent them. The absent spaces on the college admissions list are a reflection and an indictment of their criminalization. Reading the dominant culture, black children learn that their communities are deficit laden, that the threat of white supremacist violence disguised as law and order is normal, and that childhood may be fleeting. More powerful than any textbook, these “lessons” cause them to misrecognize themselves as the violent “nigga” predators white America loves to hate.

As a first grader, I remember coming home from school in Inglewood and being excited that a police officer had come to visit our class. In that turbulent world of 1970s busing there were still a fair number of white kids in the class. Our teacher was a kind but rigorous elderly white woman who lived in the neighborhood; a remnant of the city’s bygone demographics. The ramrod straight white officer who spoke to the class said that if we were ever in trouble we could go right up to any policeman and address him as “Officer Bill.” Bill handed out kid friendly safety flyers with a twinkle in his eye, whisking off to adventures in high crime. I couldn’t wait to tell my parents about kind, benevolent Officer Bill, guardian of imperiled children. When I got home my father, an activist, bitterly dispensed with this fairy tale. The police couldn’t be trusted. They were an occupying army. Some preyed on the community. Some were cold-blooded above the law killers. Growing up in the era of LAPD Chief Daryl Gates, one of the first to institute SWAT teams, naked anti-blackness was a reality camouflaged by a middle class childhood.

Year after year the litany of the dead, black folk criminally robbed of victimhood, shattered any pretense of innocence, protection or security in “tidy” neighborhoods like ours, neighborhoods that bright-eyed bushy tailed white reporters doing ghetto fieldwork were always surprised to know existed. In 1979, when an African American woman named Eulia Love was murdered at her house in South L.A. by two white police officers, it reaffirmed that black women’s bodies did not qualify as female, as fragile, as worthy of protection from state terror. My father took me to my first political rally in protest of her murder. For black women, home was no “safe” domestic space or private sanctuary as it implicitly was for white women. In the Ozzie and Harriet imagination of suburbanized L.A., black homes could never be more than a deviant subset of white Americana. Love’s murder further galvanized the community against LAPD police state suppression and occupation. It was a postscript to the 1965 Watts Rebellion and prelude to massive community resistance to Gates’ institutionalization of the chokehold (which Gates claimed blacks succumbed to more easily than “normal people”).

For African Americans migrating to California from places like Mississippi, Texas, Louisiana, and Alabama during the Great Migration era, L.A. was full of redemptive promise. It was supposed to provide a context that was radically different from the grinding everyday indignities and outright terrorism of the Jim Crow South. Yet, as Isabel Wilkerson and other black historians of the Great Migration have noted, Northern segregation was no less insidious. Blacks who attempted to buy homes in white neighborhoods were shut-out by restrictive covenants rigidly enforced by realtors and development companies. They were firebombed by white homeowners associations and vilified by angry white housewives. Black workers were discriminated against by trade unions and largely shut-out of all but the most menial jobs. While white immigrant populations advanced up the economic ladder via the GI Bill, FHA loans, VA loans, redlining, the development of new highway systems, and countless other “whitening” aids, blacks bore the brunt of systematic ghettoization.

The post Great Migration generation came of age as the para-militarization of LAPD’s police force deepened. One of Gates’s signal contributions to the War on Drugs was the battering ram, a tank ostensibly used to penetrate so-called “crack houses” which destroyed innocent citizens’ homes and inspired its own rap song.

Coming home one night in the eighties from the UCLA area, my friends and I were stopped by several Inglewood PD squad cars. Without bothering to do a license and registration check the officers jumped out wielding rifles, pointing the weapons squarely at us as they ordered us out of the car. Later, after my friend Heather’s brother was subjected to the humiliation of having to lie face down on the ground before ten cops brandishing weapons, we were told that they’d mistaken a car backfire for gunshots. Nobody would’ve given a shit if we’d been smoked. It was dark and we were black teenagers in “Ingle-Watts.”

Like Michael Brown we were college-bound, guilty until proven innocent, living in the shadow of death and the violent territorialization of the black body. Unlike him, we were spared the brunt of black America’s nightmare. In the weeks since his murder there has been national movement connecting police terrorism with the general climate of criminalization that exists in American schools. Expressing solidarity with the uprising in Ferguson, the Dignity in Schools Campaign (DSC) recently highlighted the relationship between the pushout regime in schools and the onerous police presence in urban communities. If the uprising against the spate of police murders and beatings is to coalesce into a youth movement, it must also expose the apartheid policies and mentalities that plague American schools.

As DSC St. Louis member Niaa Monee of the Missouri GSA Network commented, “I feel that we as young people really don’t have a say so in the world. It’s all about how the adults feel. Why can’t young people speak? Mike Brown didn’t deserve what happened to him, as well as all the other young people who this has happened to. Young people need to be heard, not shot. We are being criminalized and pushed out for being who we are.”

_________________________________

Sikivu Hutchinson is an educator and author of Godless Americana: Race and Religious Rebels, Moral Combat: Black Atheists, Gender Politics, and the Values Wars and the forthcoming novel White Nights, Black Paradise.

Pingback: Poverty Is Not Inevitable: What We Can Do Now to Turn Things Around | Solutions (Ideas and Proposals)