Shitty Justice: Environmental Injustice in India —Part 2

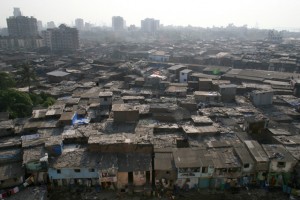

I begin again with questions (I hope you remember this is still an “interrogative text” where there are no answers as in disclosures. Therefore closure too is elusive in this text). What does it mean to have access to the poor (to latch onto the most recognizable and theorized category called class) when they do not have access to the rich? Why is their crossing into rich spaces not only impossible but an act of trespassing, punishable by law? Conversely, why is it that the rich can cross into poor spaces, especially private ones, without this being an act of trespassing? What does it mean to determine how and when and why the poor may even come within the proximity of your body and your senses, if at all? What does it mean to look upon the poor from safe distances and gilded cages? What does it mean to be part of this “tamasha” (spectacle) of privilege and where the privileged make a tamasha of the other? There is no care of/for the other in making a tamasha of the other. If you didn’t care to ask yourself why you would indulge in this tamasha then you don’t care, period. Because if you had asked yourself why the tamasha then you would have stopped it before it began and focused on making a tamasha of “you” instead. questioned your own intentions, and taken pleasure in backtracking from point B to point A in order to be clear about the how and the why. So again, what does it mean to do the kind of zigzagging between wildly different spaces? Can our answer be that it is a GEJ seminar/ field-trip requirement?  Or will our answer be because of fear and loathing (of privileged bodies collapsing due to cultural shock as it relates to spaces and their organization, their disrepair, and their smelliness)? Or because the experience of foreign space (even though your seeing it has already been mediated through someone else’s reading and description of it that seems just about right to you for reasons of your own positionality/ location) can be sensually unnerving? How do you manage your sensually revolting experiences of radically different spaces that in the Orientalist imagery are uncivilized? Do you gravitate to one over the other in the sensual sense because it is familiar? And in gravitating to one over the other only and mostly in the sensual sense do we reinstitutionalize cultural difference (as in Orientalism) in this fundamental way? And in reinstitutionalizing cultural difference via sensual horrors do we actually concede to the impossibility of caring for the other in any basic way? Honestly, did we care? Did they care? Did we as privileged citizens with rights and protections care about questionable citizens without rights and protections in the way we know these?

Or will our answer be because of fear and loathing (of privileged bodies collapsing due to cultural shock as it relates to spaces and their organization, their disrepair, and their smelliness)? Or because the experience of foreign space (even though your seeing it has already been mediated through someone else’s reading and description of it that seems just about right to you for reasons of your own positionality/ location) can be sensually unnerving? How do you manage your sensually revolting experiences of radically different spaces that in the Orientalist imagery are uncivilized? Do you gravitate to one over the other in the sensual sense because it is familiar? And in gravitating to one over the other only and mostly in the sensual sense do we reinstitutionalize cultural difference (as in Orientalism) in this fundamental way? And in reinstitutionalizing cultural difference via sensual horrors do we actually concede to the impossibility of caring for the other in any basic way? Honestly, did we care? Did they care? Did we as privileged citizens with rights and protections care about questionable citizens without rights and protections in the way we know these?

Did these questionable citizens care about our privilege that allowed us to see them in their ungilded, oily, scruffy, blackened, unsafe, make-shift, fuming, smelly, littered, cages? They never spoke and we never cared to speak to them. They sat 10 steps away from us drying our shredded plastic waste under the sun and we said nothing—not even a hello or a how are you? Why were these strangers different and not worthy of an hello than the ones we walk past everyday in our everyday comings and goings in our, familiar spaces? It cannot be language—sometimes caring doesn’t require languages to communicate. To care is to desire and to desire is to articulate that desire and to articulate that desire is to make that verbal connection and to make a connection is to link our humanity in some fragile way. Linking our humanity in no way is the most profound means of transforming spaces and lives.  But to claim that somehow our project is to transform spaces and lives is an untenable claim, one that is almost evangelical in its essence and therefore impossible. Linking our humanity, I want to claim, in and through a moment of connection that is made by forcing oneself to move one’s feet from remaining planted in a space, clean spot in a smoky in work-shed in order to feel the same heat that he/ she is feeling as they dip oily canisters in a tank of boiling soap water, maybe feel a splash of that grimy water, and ask a question. It doesn’t matter if the question goes unanswered. The point is that you made that twist and a turn and a two-step walk up to the person cleaning out a canister that will be refilled with your precious vegetable oil that you will buy in order to make your favorite samosas at home—that in trying for proximity you acknowledged why you shouldn’t be here and what you see is just that—what you see with your faraway eyes that register nothing about bodies and consciousness of being. You cannot save that which you cannot see or touch or feel or know in a profound sense.

But to claim that somehow our project is to transform spaces and lives is an untenable claim, one that is almost evangelical in its essence and therefore impossible. Linking our humanity, I want to claim, in and through a moment of connection that is made by forcing oneself to move one’s feet from remaining planted in a space, clean spot in a smoky in work-shed in order to feel the same heat that he/ she is feeling as they dip oily canisters in a tank of boiling soap water, maybe feel a splash of that grimy water, and ask a question. It doesn’t matter if the question goes unanswered. The point is that you made that twist and a turn and a two-step walk up to the person cleaning out a canister that will be refilled with your precious vegetable oil that you will buy in order to make your favorite samosas at home—that in trying for proximity you acknowledged why you shouldn’t be here and what you see is just that—what you see with your faraway eyes that register nothing about bodies and consciousness of being. You cannot save that which you cannot see or touch or feel or know in a profound sense.  You cannot save another when the distance between your self and that other is light years. You cannot save another when they do not care for you to be the one to do any kind of saving. They know who they may speak with in order to be saved. They have it figured out. You don’t. And when they see you, they sincerely hope that you have come here to save yourself rather than them. They laugh at you not because you look funny but because you do funny things like wanting to walk through their shit in order to observe their shit and tell the world that you saw shit and it somehow looked nothing like what you imagined it to be. So I suggest a different project—of looking at ourselves and our shit and our illusions about us in this world in order to build a different person. I am not even speaking of a research agenda. This is moot. It is really about finding our person in this world and changing its eye. Without this agenda of the self, we really are nothing and mean nothing. Everything is complicated only because you find that your particular lens of seeing and being in this world doesn’t fit this picture/landscape. You do not have the tools to make sense of this picture and therefore find your audacity challenged like never before. Your sense of loss is profound because you cannot control anything and if you have lived with this illusion of control for as long as you have then you are in serious trouble. Your world just became a rabbit hole and you became Alice sliding down its narrow walls into a theoretical and emotional oblivion.

You cannot save another when the distance between your self and that other is light years. You cannot save another when they do not care for you to be the one to do any kind of saving. They know who they may speak with in order to be saved. They have it figured out. You don’t. And when they see you, they sincerely hope that you have come here to save yourself rather than them. They laugh at you not because you look funny but because you do funny things like wanting to walk through their shit in order to observe their shit and tell the world that you saw shit and it somehow looked nothing like what you imagined it to be. So I suggest a different project—of looking at ourselves and our shit and our illusions about us in this world in order to build a different person. I am not even speaking of a research agenda. This is moot. It is really about finding our person in this world and changing its eye. Without this agenda of the self, we really are nothing and mean nothing. Everything is complicated only because you find that your particular lens of seeing and being in this world doesn’t fit this picture/landscape. You do not have the tools to make sense of this picture and therefore find your audacity challenged like never before. Your sense of loss is profound because you cannot control anything and if you have lived with this illusion of control for as long as you have then you are in serious trouble. Your world just became a rabbit hole and you became Alice sliding down its narrow walls into a theoretical and emotional oblivion.

*Note again the back and forth between “I” and “You’—this points to my own confusion about “me” in a familiar/unfamiliar cultural space; a confusion exacerbated by the presence of “you” or “foreign” bodies in this space. Shifting between “I” and “you” in this short reflection is almost the subconscious but shows me how much I cared about the “you,” its ways of seeing, being, and talking in “my” space/s rather than my own ways of seeing, being, and talking. I know I spent an inordinate time here reflecting on what the “you” saw and felt in order to find ways of responding to it in critical ways. I know I couldn’t but spend such a time doing this kind of explanatory work. As a post-colonial subject and also the progeny of Midnight’s Children, I will always carry the burden of Orientalism and of explaining myself through it to the “you” and watch “you” care enough to listen but have no sensual sense of what it means to carry this kind of intellectual and emotional burdens.

0 comments