Meditations on Being Right

By Lyndsey Godwin

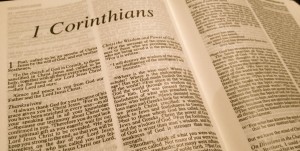

This is a sermon that was given on February 12, 2013 at the weekly chapel service held at Vanderbilt Divinity School, an inter-denominational, though historically Judeo-Christian graduate school for theological education. The focal scripture for this service was 1 Corinthians 2:1-16.

In February, I traveled with a small group of Vanderbilt Divinity School students to Creating Change, one of the nation’s largest LGBTQI gatherings of activist, educators, and community leaders.  I continue to process and unpack all I learned and absorbed there. Trying to make sense of 5, 12-hour days of radical and challenging conference time is dangerous enough, but I find myself called to try to make some of that sense, with you, in public. It’s rather terrifying.

I continue to process and unpack all I learned and absorbed there. Trying to make sense of 5, 12-hour days of radical and challenging conference time is dangerous enough, but I find myself called to try to make some of that sense, with you, in public. It’s rather terrifying.

“I do not come proclaiming the mystery of God with lofty words or wisdom…but in weakness, fear, and trembling” (1 Cor. 2:1)

My first Creating Change experience was a day-long racial justice institute. As part of the introductions and expectations, the institute’s leaders shared two ideas that have clasped my head and soul and are working on making themselves at home.

First, Rev. Dr. Jamie Washington, a black, gay, cis-gendered man and social justice trainer urged us to be present: “you can’t learn from a process or be present and engaged, if you are critiquing the process.” His was an invitation to be in that place, mind, body, and spirit—to feel the hard feelings, and push ourselves into them, rather than seeking the protection of being removed or above the experience.

This served as the precursor for one of those moments where the unseen becomes known, this dawning was the uncovering of a truth that was already at home in my heart and mind. It was like realizing that breathing keeps you alive, or taking the red pill and seeing the matrix that props up all of our lives. It was said mostly as a passing thought by Washington’s white lesbian co-facilitator, Kathy Obear; a point to ease us into our first exercise. To paraphrase:

Let go of you need to be right, to have the answer, to say the right thing. The belief that there is a right answer, or that anyone can hold it, is a myth of white supremacy culture.

Those few words continue to rattle me. Making me uncomfortable, poking my typical protections, and unnerving me at the most inconvenient times, like as I wrote this sermon.

It seems that my own daily insistence on being right, having the solution, solving “the problem,” is itself a tool of the systems that maintain oppression.

Meaning, through my own need to have the plan, the most complex comprehension of a justice issue and the ultimate, systematic solution, I am actually perpetuating racist, gendered, hierarchal oppression every waking moment.

Seeking to “fix” my working-middle class, white, educated, cis-gendered, only-child upbringing, my insistence that I can perfect my justice practice and understanding enough to “be right,” “do right,” or “do enough” is actually just supporting the powers that be.

“Being right” keeps us from taking risks, for fear of exposing the fact that we don’t actually know it all or have the answer.

“Being right” deafens our ears from critiques, questions, and points of difference, especially from those who truth doesn’t match our understanding.

“Being right” justifies colonialism, appropriation, war. It justifies the killing of Trayvon Martin, Islan Nettles, and Renisha McBride and the systematic and physical violence inflicted on countless others.

Perfectionism reinforces the idea that there is a normative narrative, a singular truth that should guide and structure our world.

This feels like a rather dangerous thing to say out loud. I hope you’ll take a deep breathe and join me on this risky journey as we explore what this might mean. We don’t journey alone, today Corinthians is one of our companions.

Holly Hearon, contributor to the Queer Bible Commentary, suggests that LGBTQI folk engage the Pauline writings to Corinth in three ways: first, seeking to represent Paul faithfully; second, reading alongside Paul for the ways the verses challenge us today; and third, resisting the assertions made in Paul’s voice. Through my lens, this scripture reveals three ways that rightness acts as a structural tool of violence, oppression, and force—particularly for hegemonic white patriarchy.

First, trying to represent Paul faithfully: The verses leading into today’s passage demonstrate a reversal in the concepts of foolish and wise. “For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved, it is the power of God…Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of this world…God chose what is low and despised in the world, things that are not, to reduce to nothing things that are.” (1 Cor. 1: 18, 20, 28).

If the wisdom of this world is foolish, then what does it mean when we tie our ideas of justice to the structures of this “right” system? For many gay and lesbian activists, marriage seems to be the answer—if same sex couples can just marry, we’ll have gotten things right.

But will same-sex marriage bring any justice to the broad diversity of families formed by homeless youth, by adopting aunts, by communities splintered by incarceration, or rattled by the unnamed stigma of mental health?

When groups like the undocuqueers speak up for a broader agenda that includes the recognition of queer and trans* identified folks in discussions of border violence, ICE raids, and family destruction through deportation; marriage advocates cry out “we can’t win with that, that’s not really our issue.”

A fuller sense of justice is rejected for a simpler notion of what is “right.”

“Being right,” insists that there is a discrete and simple way of being in the world. These Pauline writings challenge us to see that construct as foolish and false, and to find wisdom in stories, the experiences, the truths of the “low and despised.”

I am not presenting this simply as some post-modern notion of subjectivity, instead I argue that this as a central tool to dismantling oppressive hierarchies. It’s not about a single right system. It is about an ever unveiling revelation of truths. This isn’t the idea that “everyone is right” in their own context, it is the dismantling of the entire idea of right.

Reading for the challenges offer by Paul: The second chapter of Corinthians calls us to recognize the Foolish Wisdom of the Sacred as something searching, moving, in people and in God. Verse 10: “For the Spirit searches everything, even the depths of God.” The Wisdom of the spirit is not something to be held and fully known, but something slippery, something fluid, something alive.

The idea of “right” is a tool of control, a way of stopping the conversation, of silencing difference. “Winning” an argument is about being “right.” It’s about defining the narrative, to the dismissal of others, to the denial of others humanity, to the neglect of the multitude of human experience and Divine presence.

In “An Experiment in Love” Martin Luther King Jr. describes nonviolent resistance in a parallel way: nonviolence “does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win…friendship and understanding…the aftermath of nonviolence is the beloved community” (A Testament of Hope, 19). King calls us to an entirely different framework. One in which a static claim of right cannot exist because the truths are still unfolding, yet to be named, still to be heard. This framework is a continual “yes, and…” built on humility.

In “An Experiment in Love” Martin Luther King Jr. describes nonviolent resistance in a parallel way: nonviolence “does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win…friendship and understanding…the aftermath of nonviolence is the beloved community” (A Testament of Hope, 19). King calls us to an entirely different framework. One in which a static claim of right cannot exist because the truths are still unfolding, yet to be named, still to be heard. This framework is a continual “yes, and…” built on humility.

Not one of us can build justice without humility, without understanding that our context, our place in the world is not the only narrative.

What changes if we imagine the Spirit of Wisdom, and God’s love working in the same way, as forces that are searching, expansive, and continually revealing in spontaneous ways?

This notion may seem paralyzing, but instead I see it as a freeing invitation to take part in building a sense of justice that is a dynamic communal vision, continually searching and growing.

This envisioning is about speaking your truth to power, while knowing that there is more. Knowing that neither justice nor the Truth are held within you or those that think like you. The work of revealing justice and love in this world has been happening for eons before you or I, and it will continue long after. I do not hold the one answer, neither do you.

When we claim to be “right,” how are we shutting out the Spirit of Foolish Wisdom? The Wisdom of the voice marginalized, the voice too radical

Finally, let’s push back against the Corinthians passage. Despite Paul’s reversals and flowing Spirit, he’s is actually claiming God’s wisdom for himself and for those who “properly” follow Jesus through him. Paul maintains the dichotomy, designating himself and the Christians that follow him as those who “speak God’s wisdom, secret and hidden” against “those unspiritual ones” (1 Cor. 2:7, 14).

Instead, if there is no “right,” could it be that Radical Love and Radical Wisdom are both boundless, not held by any one person, or one viewpoint? Could it be that across our differences, in amongst our truths, love and wisdom are woven? Could it be that justice can only be enacted as we open ourselves, disregarding our need for the comforting “right.”

Instead of maintaining a system that insists on having the answers, we start with the humility to listen. Some of us need to listen more than others. Those of us with more privilege, more access to power, are the ones most blinded by our own ill will and conceit. In our conviction of our “rightness” we neglect of the myriad of truths.

Truths can be revealed, unfolding, expansive.

Truths complicate, mystify, and challenge the framework, our assumptions, our “knowns.”

Truths come from those seldom heard, those marginalized, those who are used by a “system of right,” rather than supported by that system.

Black, openly gay, organizationally brilliant, Civil Rights Activist Bayard Rustin, spent much of his life trying to bring all of his truths to his life and work.  In 1986 he spoke of the similarities and differences between the fights for racial justice and justice for LGBTQIA folks:

In 1986 he spoke of the similarities and differences between the fights for racial justice and justice for LGBTQIA folks:

I would like to be very hard on with the gay community, not for the sake of being hard, but to make clear that, because we stand in the center of progress toward democracy, we have a terrifying responsibility to the whole society…First, the gay community cannot work for justice for itself alone. Unless the community fights for all, it is fighting for nobody, least of all for itself…Second, gay people should not practice prejudice. It is inconsistent for gay people to be anti-semetic or racist. These gay people do not understand human rights…Third, gay people should look not only at what people are doing to us but also what we are doing to each other…Fourth, gay people should recognize that we cannot fight for the rights of gays unless we are ready to fight for a new mood in the United States (“The New Niggers Are Gays.” A Time on Two Crosses, 175-6).

Fighting for all means starting with the premise that comfort for yourself is not actually justice. When we cannot hear critique or recognize our own privilege, when we tell others their issues or lives are unimportant; how can we be building justice?

When we insist that we have the solution, how are we making room for the searching Wisdom of the Sacred? How might your own work grow, when you no longer have to be right, have all the answers, or fix all the problems?

Taking our cue from Corinthians, when “we speak of these things in words not taught by human wisdom, but taught by the Spirit,” are we also listening for the myriad of ways that Searching Wisdom is speaking truths through others? (1 Cor. 2: 4).

So, I’ll ask you the same question I am struggling with myself: Can you give up being right and all the power that goes along with it, to make room for the many truths and the radical, discomforting, searching Wisdom of God?

________________________________________________

Lyndsey Godwin recently started as the Assistant Director for the Carpenter Program on Religion, Gender, and Sexuality at Vanderbilt Divinity School. She has provided holistic sexuality education, professional training, and program design for thousands of youth, parents, and professionals over the last five years as an educator and manager at Planned Parenthood of Middle and East Tennessee. She is particularly interested in exploring the intersections of sexuality and faith within the frameworks of decision-making; relationships; and community-defined norms, practices, and ethics. Lyndsey graduated from Vanderbilt Divinity School with a Master of Divinity along with a certificate from the Carpenter Program in Religion, Gender, and Sexuality in 2008. She has developed and implemented faith-based sexual health curriculums for congregations and communities in Middle Tennessee, including Sexuality Retreats for youth programs. She has served as a “Leading Faithfully” Trainer, in partnership with the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, and is Faith and Reproductive Justice Leadership Institute Fellow with the Center for American Progress. Lyndsey is currently the Chair of the Adolescent Sexual Responsibility Committee of Alignment Nashville. She also serves as a Youth Minister and Coordinator at Glendale Baptist Church in Nashville.

Lyndsey Godwin recently started as the Assistant Director for the Carpenter Program on Religion, Gender, and Sexuality at Vanderbilt Divinity School. She has provided holistic sexuality education, professional training, and program design for thousands of youth, parents, and professionals over the last five years as an educator and manager at Planned Parenthood of Middle and East Tennessee. She is particularly interested in exploring the intersections of sexuality and faith within the frameworks of decision-making; relationships; and community-defined norms, practices, and ethics. Lyndsey graduated from Vanderbilt Divinity School with a Master of Divinity along with a certificate from the Carpenter Program in Religion, Gender, and Sexuality in 2008. She has developed and implemented faith-based sexual health curriculums for congregations and communities in Middle Tennessee, including Sexuality Retreats for youth programs. She has served as a “Leading Faithfully” Trainer, in partnership with the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, and is Faith and Reproductive Justice Leadership Institute Fellow with the Center for American Progress. Lyndsey is currently the Chair of the Adolescent Sexual Responsibility Committee of Alignment Nashville. She also serves as a Youth Minister and Coordinator at Glendale Baptist Church in Nashville.

Pingback: Beyond the Beyond: closing and opening - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire