Personal is Political: Trying to Understand (Critique): A Daughter’s Prayer

By Shelby Crosby

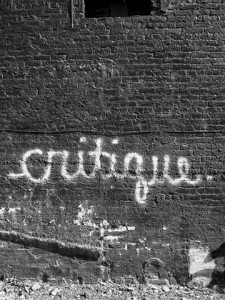

I began asking why as soon as I learned the word. To critique seems intuitive to me. To move beyond critique, even figuratively, makes me anxious and a bit angry: as though I am being asked to give up a friend or maybe a frenemy. I understand and find comfort in critique. To critique is to challenge and to challenge creates agency and action. Yet, critique is exhausting; it can deplete your energy and fracture your soul. My critiques became rebellion, rebellion against my mother’s eternal plea that I “try to understand.” Understanding felt like accommodation, like defeat, and that I could not accept. Life felt like a battle and my father became the center of it, right or wrong.

I grew up in a patriarchal household, at least in name –my mother was really in charge; she handled all the money, mostly because my father was a gambler and not to be trusted with money. However, we had to pretend that he was the one in charge … that he took care of us. We had to give him “respect” despite his often complete lack of care for our family. I started working full time and contributing to the family’s finances the summer before ninth grade. Before that I mowed lawns, babysat, and took care of my little brother. My mother worked two sometimes three jobs. My father worked–sometimes. He routinely took the family’s money and gambled it away without regard to our most basic needs. All of this I was expected to understand.

My daddy was an angry, charismatic, brilliant (with limited formal education) black man from rural Alabama. He came of age during segregation, the son of a cotton farmer. His world was filled with want, need, violence, and fear. I knew what patriarchy was before I ever heard the word and from a young age I rebelled against it. My father raised me to be a strong, independent with everyone except him: to him I was expected to be subservient and obedient (two words that never could describe me). How he thought it was possible for his daughter to be subservient is laughable; instead, I challenged him at every turn.

For example, he used the word “lady” a lot when I was a little girl: “No, Shelby, don’t ask me that. Ladies are quiet…..ladies are sweet…. ladies don’t ask questions…. ladies do as they are told…. ladies stay in the house…. ladies cook and clean…. ladies…….” So, I put him to the test one day when he told me to go mow the lawn, which didn’t seem very lady-like to me. I turned to him and very seriously said, “Daddy, ladies don’t mow lawns.” The silence that followed was deafening; we all just stopped…. tension and fear filled the air. Fortunately, my mother interceded and said, “You raised her to be this way,” which kept him from beating me. I was all of twelve when this happened. Daddy and I had many fights in our future. I now know that I was critiquing his heteronormative gender politics; back then, I just knew that it was unfair and confusing to expect me to do so much. It was wrong that my brother did nothing because he was “the little man of the house.” To me, critique was a position of power, or, more precisely, of empowerment.

Yet, those euphoric moments of defiance, which felt like empowerment, were not enough to sustain me. I was angry and frustrated all the time. I didn’t trust anyone and despite “loving” my father I could not be around him without wanting to strangle him. I found him so oppressive and belittling. It was then I realized that perhaps on a fundamental level my father and I did not like each other. We loved each other; however, we did not enjoy one another. He found me difficult and I found him to be impossibly sexist. I wanted us to appreciate one another and we had a few good years where we both tried, but ultimately we could not breach the gap. However, I am my mother’s daughter too, so I kept trying and that trying led to my career. His influence, both positive and negative, brought me to academia.

As a student, I intuitively gravitated to African American literature and Women’s Studies. I craved the knowledge that would help me understand myself and my father. And, for a while, it refocused my anger and critique. It allowed some distance; however, it was not the emotional or psychological release I thought it would be. Intellectually, education provided me with the language to understand my father historically and culturally and to critique the larger culture that contributed to our dilemma, but it did not lead to the personal healing that I longed for. In this way, critique failed me. Critique is my job; I am a literary critic. I have come to terms with that and believe that my work is literary activism. Age and historical repetition have proven to me that critique alone cannot transform a culture—that there must be a collective acknowledgement of the root problem.

In my inner life critique fails because it is circular, a pattern, a fallback position that is comfortable but often psychologically unproductive. It is a way of seeing that precludes a lot of the joy and beauty the world has to offer–and there is joy and beauty out there. My mom was an eternal optimist, despite my father’s behavior. She always saw beauty in the world; she sparkled. I lost her almost six years ago now and every day I mourn. Writing this essay is the beginning of truly honoring her wish that I try to understand because, for the first time, I am trying to understand for me.

______________________________________________________

Shelby Crosby is an Assistant Professor at the University of Memphis. Her research spans mid- nineteenth century to the early twentieth century African American literature, representations of black womanhood, and critical race theory. She is currently working on a book manuscript that examines the pervasive derogatory ideologies of black womanhood and a memoir tentatively titled, Trying to Understand: A Daughter’s Prayer.

Shelby Crosby is an Assistant Professor at the University of Memphis. Her research spans mid- nineteenth century to the early twentieth century African American literature, representations of black womanhood, and critical race theory. She is currently working on a book manuscript that examines the pervasive derogatory ideologies of black womanhood and a memoir tentatively titled, Trying to Understand: A Daughter’s Prayer.

Pingback: Beyond the Beyond: closing and opening - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire