Caring Queer Feminist Communities

By Jay Keim

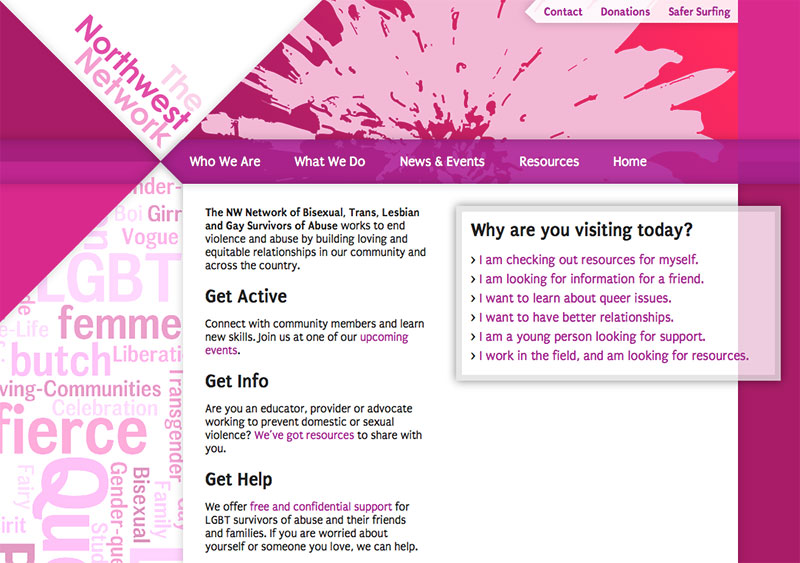

At a workshop with the Northwest Network (Seattle, USA), I was asked why I became an anti violence advocate. I felt ambivalent about the answer I came up with: I want to give the support to others that i myself was missing when i experienced violence. From the responses that other people gave I gathered that I wasn’t the only one who came to feminist anti violence work because of such experiences.

There are a couple of questions that spring from that experience for me: How do I care for myself while caring for others? How do I depend on supporting others so that a hole in myself is filled? Do I assume similarities between me and others so that i can share experiences? How do I deal with my privileges and with situations in which I reproduce systems of oppression?

By thinking about these questions, I realized that I was interested in building caring queer feminist communities, where individuals focused on caring for one another; mutual and interconnected support would be central. Occupying myself with these questions already feels like a shift in perspective to me.

There is an inner voice that tells me that I cannot indulge in caring about caring communities because there are other things to do, hetero_sexist shit to intervene in, worlds to save. Often, reacting seems like the only possible option and there is always something to react to. It can easily take up all one’s energy and usually the results are unsatisfying.

In my opinion, stepping back from that daily pressure of queer feminist interventions and actions is both a luxury and a necessity. A luxury because it means that my daily struggles aren’t so essential that they wouldn’t allow me the space to think about creating alternatives. And a necessity because i don’t think that a “fighting against” can exist without a “fighting for” _______. For me, caring queer feminist communities are not some utopian dream, but the daily question of how I want to relate to others and of how I want to deal with contradictions, failures and ambivalence in creating alternative realities. How can we create, fill and live caring communities?

Caring communities are not safe spaces and don’t pretend that they are. I don’t think that queer feminist spaces can be free of discrimination. By claiming that those spaces are safe, it becomes harder to address the violence happening within our communities and to start talking about how to build more accountable communities. Ruth Wilson Gilmore says: “safe space is not an escape from the real, but a place to practice the real we want to bring into being“ (quoted in Smith, The Problem with Privilege). Who can feel safe in so called safe spaces? Who can imagine safe spaces as an escape from oppressive realities? How is feeling safe connected to being privileged? Are there concepts of safe spaces that address interlocking systems of oppression and take people with experiences of multiple discriminations into account?

Who can feel safe in so called safe spaces? Who can imagine safe spaces as an escape from oppressive realities? How is feeling safe connected to being privileged? Are there concepts of safe spaces that address interlocking systems of oppression and take people with experiences of multiple discriminations into account?

Let’s face the reality that not everyone feels safe in queer feminist communities; and this comfort often comes at some cost, discomfort or unsafety experienced others. It is important to be careful in describing spaces or events as “comfortable” or “uncomfortable” since so often people in privileged positions use “being uncomfortable” to silence or curtail discussions of oppression. The question is who is actively excluded (e.g. in womendyketrans* spaces) and who is excluded by not being actively welcomed. By arguing for caring communities, I am not arguing against creating identity-based spaces and/or excluding people from spaces when they violate other peoples’ boundaries or act discriminatorly. But I would also like to raise the question of who has the privilege of claiming such spaces and who is always forced to face potential discrimination in these spaces.

I like the term “caring” because it points to the fact that creating spaces where people can feel comfortable is an ongoing activity. Safety isn’t something that is just there; people have to care about safety, making people feel safe and welcome. It shows also that I depend on other people to care for me and to care about my issues. It isn’t something that I easily admit to myself that I need other people to take my experiences of discrimination and violence seriously so that my communities become a space where i can feel at home.

Feminist spaces often focus on the supposedly shared issue of sexism while some forget that sexism doesn’t look the same for everyone. How we experience street harassment for example is deeply shaped by the social positions we inhabit and/ or the way we are perceived by others. Prioritizing certain issues from a certain perspective reproduces heterosexism in feminist communities because heterosexuality is once again declared the norm. For example, the conversation around reproductive rights is often limited to the access to abortion while including queers in safe sex education is not addressed. Queer feminist spaces become caring communities when they care not only about sexism but always about interlocking systems of oppression, e.g. racism, transphobia/ cissexism, ableism, classism, antisemitism, etc.

Caring communities are about practicing solidarity and allyship. How can I offer a space where people can take care of themselves? How can i be a good ally in self-care? For me, it is important not to think that i have to take up the responsibility of taking care of everybody. First of all, I think that it is important to reflect on how caring for others can stop oneself from caring for oneself. Although I also think that these two things don’t have to be mutually exclusive – which I’m learning by being in caring communities. But most importantly, I cannot and will not always know what other people need. I don’t want to buy into the narcissitic idea that other people are depending on me to save them, or that I know best what is good for them. That is a structure of domination that hides itself behind the argument of caring. So I instead think about showing solidarity, being an ally to others and being accountable in my solidarity and allyship. It is something which others can take me up on or not. It is my decision to offer support and to practice different ways of showing it, but in this context I’m not the person defining the terms of what good care means. But I think it is also important to be mindful of the ways that solidarity is distributed: Who gets solidarity from whom? Who expects solidarity from whom? How do you show solidarity? Are you only showing solidarity when you can stay in your comfort zones?

So how can we build caring communities in which people feel cared for, even if we can’t promise safety at all times?

There are two caring practices that I would like to talk about: creating spaces for different opinions and priorities and creating space for different approaches and capacities.

Creating space for different opinions and priorities can happen when i bring a willingness to question my own priorities to the table. Therefore, I need to reflect on how these priorities are connected to how my privileges shape the perspective I have on queer feminist issues. What falls under my definition of sexism? Do I perceive sexism as being racialized? And how does that shape my antisexist activism? If I create space for different opinions and priorities, I have to ask myself which of my own priorities I give up, and how I complicate my daily experiences and perspectives in the world, in order to be a good ally to other issues that then become pressing matters to me as well.

Creating space for different opinions often includes creating space for contradictions and that allows for practice of contradicting each other. I have to give up the idea of a harmonious space where everybody agrees with everybody – which often means that people are made to agree with the dominant opinion. It allows reflection on which forms of power and control are at work in queer feminist communities and how systems of oppression are reproduced in daily interactions. For me, caring does not work without criticizing each other. Sometimes you just need some tough love. What is important to me in criticizing others is to reflect on how i like to be criticized and to think about where my critique comes from. Do I call someone out because they haven’t behaved in a responsible and accountable manner? Does my calling them out allow them to change – if I want to give them the opportunity? In other words, does my critique come from a place of solidarity? Or do i criticize someone because i want them to agree with me and make them act according to my own ideas? I think it is important to reflect on my own intentions and purpose when criticizing others and to be open to being criticized.

Being aware of differences also includes creating space for different approaches and capacities. How do I approach feminist activism? And how do other people approach it? How is my approach shaped by norms of productivity and efficiency? When I’m stressed out, I recognize that i can be very harsh and I can become more judgmental towards others when they don’t do things the way I do them or I want them to do them.

I have started to practice recognizing and accepting different approaches, needs and limits. I think it is important to reflect on different reasons why people supposedly do “less.” I would like to inform myself about different capacities so that U don’t force other people to refer to their exhaustion, limits and burnouts to make me depart from the expectations i might have of them. I hope that learning about the limits of others will also lead towards more softness with myself.

In caring communities, there also needs to be space for fun, playfulness, and celebration. For a long time, caring meant supporting others when they weren’t doing well. It started to include caring for myself when i wasn’t doing well. It took me a long time to realize how limiting this perspective on caring is. I think it is important to create breaks and to give each other a break once in a while. Often, I only stopped being active in activism when I reach a point of being unable to continue. It is interesting to me how I have connected being active with activism and being inactive with resting. But I also know that self-care requires a lot of active making of space and time. And then there are all the fun activities I would love to see considered as being part of queer feminist activism: having an instant dance party in someone’s kitchen, coming together for dinner, sitting with each other in silence, sharing laughter – all these moments in which caring communities become places of growing and grown connectedness.

________________________________________________

For many years, Jay Keim has been organizing around the issues of violence in queer feminist communities, self-care and collective empowerment. They write about self-care and activism in German on their blog Virtual Retreat Center (http://virtualretreatcenter.blogspot.de/) and work at LesMigraS, the antiviolence and antidiscrimination area at the Lesbian Counseling Center, in Berlin, Germany (http://lesmigras.de/english.html).

For many years, Jay Keim has been organizing around the issues of violence in queer feminist communities, self-care and collective empowerment. They write about self-care and activism in German on their blog Virtual Retreat Center (http://virtualretreatcenter.blogspot.de/) and work at LesMigraS, the antiviolence and antidiscrimination area at the Lesbian Counseling Center, in Berlin, Germany (http://lesmigras.de/english.html).

Pingback: Beyond the Beyond: Closing and )pening - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire