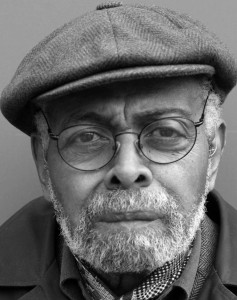

Because Someday Someone Should Ask, “Do You Remember Where You Were When Amiri Baraka Died?”

By Guest Contributor on January 17, 2014By khoLi

All those major events we lived through. If we responded to them as conscious Black intellectuals, we had to try to become soldiers ourselves. That is why we wrote the way we did, because we wanted to.

—Amiri BarakaDo not leave the arena to the fools.

—Toni Cade Bambara

Amiri Baraka has died.

I am currently writing a dissertation, “Running Out of Time: Radicalism, Resistance, and the Future of African American Literature.” In it, a full chapter is dedicated to the reclamation and restoration of Amiri Baraka as a central figure to not just the Black Arts Movement (BAM) but also the black feminist movement, African American literature, and black radical praxis as a whole. And yet, today, it is hard for me to find the words to explain the truth of why we—particularly as feminists seeking and providing socio-political and cultural critique of anti-feminist, racist, and imperialist politics—need to hold fast to the legacy of this legend. I don’t find it hard because there’s no truth in the sentiment, but rather, because most of our ability to see truths depends much more on where we are in our own personal and intellectual development—how prepared we are to see and know such truths, as opposed to how said truths are presented to us.

Also, Amiri Baraka has died. And I am in no mood to argue.

In the introduction to my dissertation, I convey the urgent necessity of detangling the work (the makings and contributions) of an individual author from the legacy (the teachings, and tellings, and understandings) of said author as it has been constructed (both inside and outside of the academy) within a historically linear tradition. For example, I explain:

I am a black girl that has found myself in a PhD program in English literature…because…I believe people need to know how to listen differently, to relate differently, to wait patiently as a story or conversation or argument or answer unfolds across more than a few pages, a few years, decades, maybe even the length of a century…I came to the academy hoping to develop that feeling for myself and, in doing so, articulate it for and ignite it in others.

I come to this essay hoping to do the same.

Over 30 years ago, Toni Cade Bambara wrote The Salt Eaters, reminding us that “everything now has been before and will be again in this new way, in a changed form, in a timeless time.” So today, when traditional studies of African American literature and life seem to be in a concertedly hurried effort to move towards a world marked as post-racial, when scholars and critics (intentionally or not) diminish much of the work of the Black Arts Movement by too-soon marking the beginning of each successive literary movement as separate from BAM or as a conclusive end to it, and when (even in supposedly commemorative writing) writers erroneously refer to Baraka “as a gadfly whose finest hour had come and gone by the end of the 1960s,” I find myself in no mood to be another critic trying to prove to anyone the impact of Amiri Baraka on this world.

Because I am a black feminist woman that often has to legitimize or rearticulate my own personal truths for someone else’s convenience, I find myself struggling to speak for someone who has already spoken his truth so clearly. According to Margalit Fox, “There was no firm consensus on Mr. Baraka’s literary merit, and the mercurial nature of his work seems to guarantee that there can never be.” However, even without whatever firm consensus Fox seeks in order to contextualize the merit of Baraka’s canon, Baraka has already articulated a clear understanding of his development, his growth and his work as a black radical, as well as his literary merit and contributions to the African American literary tradition.

In the introduction to The Leroi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader, Baraka confirms, “The typology that lists my ideological changes and so forth as ‘Beat-Black Nationalist-Communist’ has brevity going for it, and there’s something to be said for that, but…it doesn’t show the complexities of real life…it was easier to be heard from with hate whitey than hate imperialism!” In a hypothetical conversation, the poet and activist continues,

‘You mean that’s not accurate?’ Dick or Dixie Dugan wd counter.

‘Well, yes and no,’ I’d drawl …

… [T]he truth is that in going toward and away from some name, some identifiable “headline” of one’s life, the steps are names too, but we ain’t that precise yet. We go from step 1 to step 2 and the crushed breath away from the ‘given’ remains unknown swallowed by its profile as what makes distance.

As someone who’s made changes in my own naming, as a woman who will later have to deal with the emotional, psychical, and political implications of taking or not taking the surname of my partner, and as an academic who studies the differences between the ways in which we name ourselves and the ways that we are named by others, I understand how labels often eclipse the work we’ve done to don them. Baraka speaks to this when he writes,

My writing reflects my own growth and expansion, and at the same time the society in which I have existed throughout this longish confrontation. Whether it is politics, music, literature, or the origins of language, there is a historical and time/place/condition reference that will always try to explain exactly why I was saying both how and for what.

In a 2009 visit to Brent Edwards’ graduate seminar, “Black Radicalism and the Archive,” Baraka expounded upon his lifetime as a poet and activist, saying,

You have a responsibility to reject the future. But you can’t do that unless you know the past.

And again.

You’ll find those things too … imitations of yourself that you didn’t find that interesting.

And again.

… the nationalism is not sufficient.

And again.

… being black is not sufficient.

And again.

You’ll never catch up with yourself.

Today, thinking about my own ever-evolving mind and the writing I produce as discrete expressions of my varying emotional, spiritual, psychical, and even physical states, then thinking about the slew of Stanley Crouches who will rush to condemn Baraka’s canon of expressions as “an incoherent mix of racism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, black nationalism, anarchy and ad hominem attacks relying on comic book and horror film characters and images” as opposed to what Baraka calls the “materialization of ideas” through “struggle, change, struggle, unity, change, movement…and motion,” I am even more weighted by the eerie feeling that we are running out of time.

Time will never stop in any real sense.

However, without recognizing and valorizing the impact of individual radical thought—without seeking to understand the black intellectual as a dynamic human being who, in understanding that the master’s tools may never dismantle the master’s house, has often tried to become soldier—we run the risk of continuously allowing the powerful, sometimes triggering, and at all times changing, desires and dreams and lives of black thinkers to be subsumed as brief utterances in a long master narrative dismissing black experiences as solely the collective quest for justice and equality. Yes, we have and do and will continue to seek these things. Still, not all of us are equally committed at the same time, in the same ways, and with the same actions. We are and will always be more.

Amiri Baraka has died.

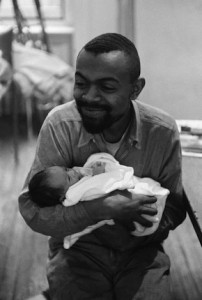

And although he is surely greater than any signal or signpost—a poet/leader/teacher/lover/father whose “change of heart and head is testimony to his honesty, energy and relentless search for meaning”—let his legacy serve as a reminder that we are allowed to wrestle oppression in any manner we insist, and in doing so, we are and forever will be much more than they will ever have to say of us. Let his passing remind us that we are one in a long line of warriors, that it is not our namings or differences that divide us, but “our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences,” that our desires and beliefs and experiences must be spoken. As Audre Lorde once declared,

Once you start to speak, people will yell at you. They will interrupt you, put you down and suggest it’s personal.

And the world won’t end.

And the speaking will get easier and easier.

_________________________________________________________

A Ph.D. candidate at Rutgers University, khoLi spends the bulk of her time using mystical powers to conjure enough hours in the day to complete her dissertation, appropriately titled, “Running Out of Time: Radicalism, Resistance, and the Future of African American Literature.” She mixes her love for literature, creative copy, brand development, and pop culture in order to discuss the generation and progress of trans-historical moments in black resistance while worrying the lines of identity and power.

A Ph.D. candidate at Rutgers University, khoLi spends the bulk of her time using mystical powers to conjure enough hours in the day to complete her dissertation, appropriately titled, “Running Out of Time: Radicalism, Resistance, and the Future of African American Literature.” She mixes her love for literature, creative copy, brand development, and pop culture in order to discuss the generation and progress of trans-historical moments in black resistance while worrying the lines of identity and power.

You may also like...

1 Comment

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Because Someday Someone Should Ask, “Do You Remember Where You Were When Amiri Baraka Died?” | Radical Historiographies