For the Love of Freedom: Writing, Radical Praxis and the Transformative Power of a Slave’s Words

By Ernest L. Gibson, III

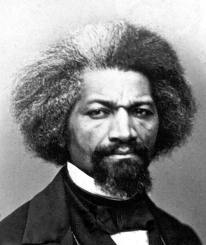

When Frederick Douglass wrote “My feet have been so cracked with the frost, that the pen with which I am writing might be laid in the gashes,” he made legible one of the most profound relationships experienced within American slavery. It is within the iconography of the literate slave that I locate the transformative power of radical love – a love engendered by and inseparable from the pain of suffering. Admittedly, the discourse of love as radical praxis might shy away from a “post”-modern reading, where an enslaved person’s existential plight is rendered beautiful through an insatiable desire for learning, and, by extension, writing. But what Douglass does so well is couple the condition of his oppression with the possibility of its cure in such a manner which lends itself to new interpretations. As he told those of his day and those who were to follow, albeit metaphorically, it was his radical love for freedom that precipitated his relationship with the literary. Even more, the relationship established between traces of enslavement and the act of writing articulates just how transformative a radical love can be. In the end, aside from the horrific portrait of slavery and the melancholic loneliness of escape, Douglass’ narrative highlights how love pushes one beyond the throes of terror and into the beauty of the unimaginable. This is what James Baldwin, over a century later and operating in a completely different context, would call the “stink of love.” Douglass dared to love freedom at a time in which freedom for people of African descent was messy. He was not afraid of the messiness of it all, not hampered by the precariousness of reciprocity – freedom often did not love black folk back, not deluded by its promises or possibilities; rather, he pursued his love out of the innate hope that its acquisition had the power to transform. And perhaps we can call this a Kierkegaardian “leap of faith”; perhaps we understand this as a natural longing for those shackled by hate. Either way, it signifies that radical love, in its rawest, unshackled form, endows the lover with the endurance to construct something magical out of nothing, to carve the sun of a new reality from the storms of a peculiar past, to push a man to sing when the tongue of his spirit has been lynched. You see, even as Douglass acknowledges the remnants of another’s hate, he is able to write about the joy of his freedom. In this sense, Douglass’ writing symbolizes the legibility of love, as he prescribes how one pursues the longings of the heart. More importantly, this reading of the literary and the iconographic offers motivation for seemingly new articulations of love: The heterosexual man who chooses to love beyond his privilege, the woman who pushes to love against the backdrop of history’s patriarchy, the queer person who dares to love in spite of societal hate – they will all find a freedom only granted by radical love. It is the daring to love, despite the suffering that may come with it, that truly aligns one with freedom. This is what African American literature teaches us: Every word is a testament of love – a radical love, every sentence born out the hearts of a people who understood that the love of freedom could transform their lives and how they, through the love of the literary, could share that love with a world yet unborn and transform those whose spirits are “cracked by the frost” with a warmth as healing as the very blood flowing from their fingers into their pens.

When Frederick Douglass wrote “My feet have been so cracked with the frost, that the pen with which I am writing might be laid in the gashes,” he made legible one of the most profound relationships experienced within American slavery. It is within the iconography of the literate slave that I locate the transformative power of radical love – a love engendered by and inseparable from the pain of suffering. Admittedly, the discourse of love as radical praxis might shy away from a “post”-modern reading, where an enslaved person’s existential plight is rendered beautiful through an insatiable desire for learning, and, by extension, writing. But what Douglass does so well is couple the condition of his oppression with the possibility of its cure in such a manner which lends itself to new interpretations. As he told those of his day and those who were to follow, albeit metaphorically, it was his radical love for freedom that precipitated his relationship with the literary. Even more, the relationship established between traces of enslavement and the act of writing articulates just how transformative a radical love can be. In the end, aside from the horrific portrait of slavery and the melancholic loneliness of escape, Douglass’ narrative highlights how love pushes one beyond the throes of terror and into the beauty of the unimaginable. This is what James Baldwin, over a century later and operating in a completely different context, would call the “stink of love.” Douglass dared to love freedom at a time in which freedom for people of African descent was messy. He was not afraid of the messiness of it all, not hampered by the precariousness of reciprocity – freedom often did not love black folk back, not deluded by its promises or possibilities; rather, he pursued his love out of the innate hope that its acquisition had the power to transform. And perhaps we can call this a Kierkegaardian “leap of faith”; perhaps we understand this as a natural longing for those shackled by hate. Either way, it signifies that radical love, in its rawest, unshackled form, endows the lover with the endurance to construct something magical out of nothing, to carve the sun of a new reality from the storms of a peculiar past, to push a man to sing when the tongue of his spirit has been lynched. You see, even as Douglass acknowledges the remnants of another’s hate, he is able to write about the joy of his freedom. In this sense, Douglass’ writing symbolizes the legibility of love, as he prescribes how one pursues the longings of the heart. More importantly, this reading of the literary and the iconographic offers motivation for seemingly new articulations of love: The heterosexual man who chooses to love beyond his privilege, the woman who pushes to love against the backdrop of history’s patriarchy, the queer person who dares to love in spite of societal hate – they will all find a freedom only granted by radical love. It is the daring to love, despite the suffering that may come with it, that truly aligns one with freedom. This is what African American literature teaches us: Every word is a testament of love – a radical love, every sentence born out the hearts of a people who understood that the love of freedom could transform their lives and how they, through the love of the literary, could share that love with a world yet unborn and transform those whose spirits are “cracked by the frost” with a warmth as healing as the very blood flowing from their fingers into their pens.

________________________

Dr. Ernest L. Gibson, III is an Assistant Professor of English at Rhodes College. He received his BA in Philosophy from Fisk University; his MA in American Studies from Purdue University and another MA along with his PhD from the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. He was the Thurgood Marshall Fellow of African and African American Studies at Dartmouth College before assuming his position at Rhodes College. His teaching/research interests include African American Literature, Male Studies, Black Popular Culture and Literary/Cultural Theory. His current book project examines salvific manhood, intimacy and emotion in the novels of James Baldwin.

Dr. Ernest L. Gibson, III is an Assistant Professor of English at Rhodes College. He received his BA in Philosophy from Fisk University; his MA in American Studies from Purdue University and another MA along with his PhD from the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. He was the Thurgood Marshall Fellow of African and African American Studies at Dartmouth College before assuming his position at Rhodes College. His teaching/research interests include African American Literature, Male Studies, Black Popular Culture and Literary/Cultural Theory. His current book project examines salvific manhood, intimacy and emotion in the novels of James Baldwin.

0 comments