Somebody Confiscated My Field Notes: Reflections on Occupied Palestine

By Erica Lorraine Williams

This May, I traveled to Occupied Palestine to participate in a faculty development seminar that involved visiting universities in East Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Nablus and Hebron.[1] As an anthropologist who has spent a lot of time in Latin America, I was thrilled at the prospect of traveling to a region where I had no previous experience and limited prior knowledge. I felt the need to disconnect from the technology of my iPad, laptop, and iPhone. Perhaps I was being nostalgic for the ‘old days’ of handwriting and snail mail, but there was something about writing in a journal that excited me. I wanted to go back to the basics. I arrived in Palestine with two thin, compact journals in my favorite color, and immediately went into ethnographic “fieldnotes” mode. I wrote down descriptions of everything I saw around me, information that I learned from the scholars and students, my impressions, and my feelings at the end of each long, packed day. I wrote in order to remember, so that I would be able to share what I learned when I returned home.

Before the trip, we were warned about the intense security at Ben Gurion International Airport: if we arrived with books or articles about Palestine, we could be held for questioning or even denied entry. Airport security could go through our computer files, emails, and social media accounts. A previous participant was detained and even strip-searched by Israeli airport security just for having a brochure from a Palestinian university. In an attempt to avoid a similar outcome, on the last day of the program we walked to the nearby post office in East Jerusalem to mail our “contraband” materials. I paid 70 shekels (about $35 USD) to mail a bulky, white envelope that contained my journals, business cards from Palestinians colleagues, brochures from Palestinian universities and civil society organizations, and CDs of Palestinian music. I wrapped several layers of clear tape around the package, hoping that I could guarantee its security and impermeability. Other participants mailed boxes full of scholarly books, posters and detailed maps of Israel/Palestine that showed the ever-encroaching presence of Jewish settlers on Palestinian lands.

Upon returning to Atlanta, I was a bit nervous that the package would be lost in the mail or confiscated. So imagine my excitement a few weeks later the package arrived! However, when I opened it, I discovered that my journal full of notes was missing! I felt devastated and violated. I felt much like Darnell Moore in his essay, “The Occupation Stole My Words, June Jordan Helped me Relocate Them“; except for my words were quite literally stolen! There is something cruel and unusual about separating an anthropologist from her field notes. I couldn’t believe that an agent of the Israeli government had actually taken the time to sift through all of my belongings and make a decision as to what I should be allowed to have. They even re-taped the envelope to make it look exactly as it did when I handed it to the post office employee. What was so dangerous and threatening about my handwritten notes? I felt outraged, but I realized that this was nothing compared to what Palestinians experience everyday. When I told my Palestinian friend what happened, she said, “So expected! They don’t want anybody to know what is really going on here!”

Well, if I only have my memory to rely on instead of my notes, then so be it. The Israeli government may have been able to take away my notes, but they can’t take away the stories I heard, the things I saw, and the connections I made with Palestinians. I repeatedly heard Palestinians describe how the Israeli Occupation affects every aspect of their lives – where they can live, who they can marry, where they can work, where they can study, and more. The Israeli government has spent a lot of money (supported by U.S. taxpayers) to build up the ugly infrastructure of apartheid – the Wall, barbed wire, checkpoints, settler roads and Palestinian roads, etc. We met a Palestinian woman in Bethlehem whose house faced the Wall. Israeli security forces forbade her from going onto the roof of her house because it was higher than the Wall. They would shoot her if she defied their order. I remember that every university that we visited had a plaque to commemorate the martyrs – students who had been killed by Israeli defense forces.

Palestinians are severely restricted in their movements. If they live in the West Bank or Gaza, they are not allowed to travel to Jerusalem without permission from the Israeli state, nor are they allowed to use Ben Gurion International Airport in Tel Aviv. I met a woman from Gaza at the Yabous Cultural Center in Jerusalem who had not seen her family in Gaza in over ten years. When she applied for residency in Jerusalem for work, she basically gave up the right to ever go back to Gaza again. In order to have a family reunion, they had to meet in Egypt. I met a Palestinian woman professor who was engaged to a Palestinian-American filmmaker. Not only was her fiancé’s request for residency in Ramallah denied by the Israeli government, but he was also ordered to leave Ramallah by the end of May. Meanwhile, people are coming from around the world to attend their June wedding. I spoke to a professor who commuted from Jenin to Al-Quds University. He generally woke up at 5:00 AM to give himself two hours to get through the checkpoints. Sometimes the Israeli soldiers at the checkpoint would make him pull his car over and wait for an hour for no reason. They didn’t believe that he was an “Arab Ph.D.” Tears welled in his eyes (and mine) as he described how he and several members of his family had been in prison, and his family home had been demolished.

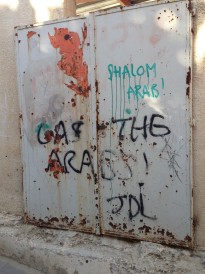

The Israeli government can take away my notes, but they can’t take away the memory of the walking tour led by the Temporary International Presence in Hebron. They can’t take away the heaviness of history in this city that I felt in my own body. The Palestinian “open-air” market was caged in with a fence that covered the spaces not covered by tarps. We soon realized the reason for the fence: it was to catch the cement, stones, dirty diapers, and other objects that the Israeli settlers living in the tall buildings overlooking the market would throw down onto the market. However, the fence could not stop the dirty water, acid, and other liquids that were sometimes tossed out of the windows. We walked through the Jewish settlement in Hebron where Palestinians were forcibly removed from their shops, homes, and livelihoods. Now it looks like an abandoned ghost town. We saw metal poles ridden with bullet holes and the words, “Gas the Arabs” spray-painted on the side of a wall.

Having my journal of field notes confiscated by the Israeli state impressed upon me the urgency of sharing these stories. I met Afro-Palestinians at the African Community Center in Jerusalem, whose fathers and grandfathers had migrated from Chad, Nigeria, Senegal, and Sudan generations ago. We toured Old City Jerusalem with an Afro-Palestinian man who had been incarcerated for 19 years for resisting the Occupation, and visited the Abu Jihad Prisoner’s Movement Museum at Al-Quds University. I won’t forget seeing all of the Israeli flags flying outside lands and homes occupied by settlers in Old City Jerusalem. How many stories of Palestinian loss, demolished homes, forced relocations, and suffering were behind those proudly planted flags that marked “their territory”? I won’t forget walking through the narrow alleys of Amari Refugee Camp in Ramallah, and visiting a women’s program and a center for the care of the disabled and elderly. I won’t forget Samia Boutmeh, a SOAS-trained Palestinian economist in the Centre for Development Studies at Birzeit University, saying, “We want solidarity, not charity.” She pointed out the contradictions of U.S. taxpayers’ dollars going to bolster Israeli security forces, while U.S. development agencies give aid to improve conditions in Palestinian refugee camps, to pave segregated roads, to build schools, and fund civil society organizations. Instead of giving aid to help Palestinians live a little better under Occupation, she said, the U.S. should stop supporting Israeli Occupation.

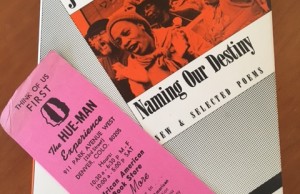

The Israeli government may have taken my notes, but it can’t silence me. Feminists have long discussed the importance of speaking, naming, and breaking silences. As Audre Lorde (1980) said, “the transformation of silence into language and action is an act of self-revelation, and that always seems fraught with danger.” Rather than be silent, I will give up my dependence on field notes and write from memory. I learned valuable lessons about resistance from Palestinian faculty who held classes hidden in people’s homes when Israeli security forces shut down their universities during the 2nd Intifada, from Palestinian hip hop artists, the Al-Kamandjati music school in Ramallah, the Yabous Cultural Center and the Edward Said Music Conservatory in Jerusalem. Even under the Occupation, Palestinian children are being taught to value their cultural heritage. In Bethlehem, we walked down a narrow road that ran alongside the “Apartheid Wall.” This clear symbol of oppression was covered with beautiful art and words of resistance and hope for an end to the Occupation. There was even an oral history project to capture the experiences of Palestinian women experiences during the Intifada. Whatever the Israeli state throws Palestinians, they manage to find a way to resist and to hold onto their humanity.

My confiscated journal contained the facts, figures and details from presentations on Jewish settlements in the West Bank and the Wall, the Right to Education Campaign, the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions Movement and the Academic and Cultural Boycott Campaign. But what remains is the impression, the inspiration to read more and learn more about these issues. The Israeli Occupation of Palestine is a feminist issue, a queer issue, a civil and human rights issue that should concern us all.

[1] Cynthia Franklin, another participant in the seminar, has already published an article about her experience here http://portside.org/2013-06-13/sightseeing-apartheid-state-ben-gurion-west-bank

________________________________

Erica Lorraine Williams is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Spelman College in Atlanta, GA. She earned her Ph.D in Cultural and Social Anthropology from Stanford University in January 2010, her M.A. in Cultural Anthropology from Stanford in 2005, and her B.A. in Anthropology and Africana Studies from New York University in 2002. Erica’s research has focused on the cultural and sexual politics of the transnational tourism industry in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Her forthcoming book manuscript, Ambiguous Entanglements: Sex, Race, and Tourism in Salvador, Brazil, won the National Women’s Studies Association/University of Illinois Press First Book Prize. She is embarking on a new research project on Afro-Brazilian feminismt activism, sexuality, and religiosity in Salvador, Brazil. During the Spring 2012 semester, Williams was a Mellon/HBCU Fellow at the Franklin Humanities Institute at Duke University. She has also held fellowships from the Future of Minority Studies Project (2011), UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Black Studies (2008-2009), and UNCF/Mellon Faculty Programs (2009). At Spelman, she is Co-Director of a five-week summer study abroad program in Salvador. Her teaching interests include: Introduction to Anthropology, Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Gender and Sexuality, Gender and Transnationalism, Sexual Economies, Race and Identity in Latin America, and African Diaspora and the World (ADW).

Erica Lorraine Williams is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Spelman College in Atlanta, GA. She earned her Ph.D in Cultural and Social Anthropology from Stanford University in January 2010, her M.A. in Cultural Anthropology from Stanford in 2005, and her B.A. in Anthropology and Africana Studies from New York University in 2002. Erica’s research has focused on the cultural and sexual politics of the transnational tourism industry in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Her forthcoming book manuscript, Ambiguous Entanglements: Sex, Race, and Tourism in Salvador, Brazil, won the National Women’s Studies Association/University of Illinois Press First Book Prize. She is embarking on a new research project on Afro-Brazilian feminismt activism, sexuality, and religiosity in Salvador, Brazil. During the Spring 2012 semester, Williams was a Mellon/HBCU Fellow at the Franklin Humanities Institute at Duke University. She has also held fellowships from the Future of Minority Studies Project (2011), UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Black Studies (2008-2009), and UNCF/Mellon Faculty Programs (2009). At Spelman, she is Co-Director of a five-week summer study abroad program in Salvador. Her teaching interests include: Introduction to Anthropology, Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Gender and Sexuality, Gender and Transnationalism, Sexual Economies, Race and Identity in Latin America, and African Diaspora and the World (ADW).

Pingback: Somebody Confiscated My Field Notes: Reflections on Occupied … | Ramy Abdeljabbar's Palestine and World News

Pingback: Somebody Confiscated My Field Notes: Reflections on Occupied … | Ramy Abdeljabbar's Palestine and World News

Pingback: Somebody Confiscated My Field Notes: Reflections on Occupied … | Ramy Abdeljabbar's Palestine and World News

Pingback: Somebody Confiscated My Field Notes: Reflections on Occupied … | Ramy Abdeljabbar's Palestine and World News

Pingback: Somebody Confiscated My Field Notes: Reflections on Occupied Palestine | Ramy Abdeljabbar's Palestine and World News

Pingback: Somebody Confiscated My Field Notes: Reflections on Occupied Palestine | Ramy Abdeljabbar's Palestine and World News

Pingback: Somebody Confiscated My Field Notes: Reflections on Occupied Palestine | Ramy Abdeljabbar's Palestine and World News

Pingback: Somebody Confiscated My Field Notes: Reflections on Occupied Palestine | Ramy Abdeljabbar's Palestine and World News