The Occupation Stole My Words, June Jordan Helped me to Relocate Them

Dedicated to June Jordan (who still lives among us)

Dedicated to June Jordan (who still lives among us)

My friends had expected retellings of my journey when I arrived back from Israel and the Palestinian territories at the start of the year, but I could not locate the words necessary to describe my experience because they were snatched from my tongue. They were occupied by fear. I remained silent for several days and avoided extended conversations regarding my trip. I felt a strange and profound sense of loneliness and struggled to find feeling and meaning. I was made silent. And it makes sense why.

Terror compels us to mute our voice and to still reaction. My preparation for the trip, a delegation (the first) of queer and trans activists to Palestine, consisted of a few fundraising efforts and me figuring out the best way to explain to potential financial supporters that I would use their dollars to cover my trip to Palestine, which provoked fear regarding my safety among many. In the minds of some of my friends, the mention of Palestine and the Arab world conjured images of the terrific and terrifying, of the terrorist and of the terrorizing. And for others, it provoked feelings of detestation. It was those folk who warned me about the possibility of conversion into some sort of pro-Palestinian / anti-Israel activist who, by sway of anti-Semitic evangelists, might be emboldened upon my return to stand on the wrong side of justice. Some others had given me money overly impressed by my seeming commitment to the Israeli cause and my ostensible respect for Zionist pronunciations of Israel as the chosen of G-d. They assumed, I guess, that my Black church upbringing would somehow shape my view of Israel in relation to Palestine or that the Hebrew Scriptures would be the hermeneutical lens through which I would come to understand conquest as a divine order of events as opposed to a dehumanizing project of colonization by mortal hands.

Mortal hands: the anthropomorphic hands of imperialism: the tight grip of state-sanctioned militarized hands on guns controlling land and monitoring mobility and throwing tear gas and slamming elderly women to the ground and disappearing children and steering the demolition trucks that carve zeros in the ground: those hands are the hands of G-d?

When I arrived at the Ben Gurion Aiport in Tel Aviv, the first hands that were extended in my direction were the hands of airport security. The guard wasted no time in requesting my passport. When I made it to the security booth, I was greeted with, yet, another look of suspicion. I responded with the appropriate performance of tenseness. And, why shouldn’t I have? I landed in Tel Aviv black, male and bearded carrying the rationale for my journey in my mind and a sketchbook with risky words in my bag. Security asked me for my passport and inquired about the purpose of my travels. I gave too much, literally. I handed over my passport, my notebook and my courage, upon request. I failed to recall, however, that I had prophesied that exact moment some time ago right there on the first page of my book. Security discovered the same when he opened page one in my scrapbook and read these words scribbled and crossed out in black ink on the white page:

We know. And, it’s because of this that our “knowing”…that our voices, experiences, stories, life worlds, identities, politics, visions, and bodies are often in danger of being, ostracization, subsumption, violated, violation.

Knowing is dangerous, for many of us: for (non)white, (non)male, (non)abled, (non)polis, (non)bougpetit bourgeois, (non)straight bodies. Those imaged as (non)sense material existing in the world (non)plussed. But, we know!

And, our “knowing” is dangerous. For it is [within] that we hold truths that critique tailored systems of domination fashioned to…

…silence us?

After reading the words that I forgot existed, security kept my passport and itinerary and asked that I take a seat in the waiting area. I was not alone there, but there were others whose heads were adorned with the حجاب (hijab), whose skin colors were differently hued, and/or whose reasons for travel spurred distrust. And, our knowing was dangerous.

We knew why we were there. I knew. I had no other reason to arrive in Tel Aviv, black, male and bearded, except to pose a threat to the state of Israel, right? I knew what they were thinking. I knew that I appeared dangerous: a security problem whose entrance into the country absorbed security like the others who nervously waited with me. The really polite guard who invited me into his office for questioning asked my purpose for traveling and requested “this notebook.” I gave him both. I mentioned that I was Christian and that I am a seminarian graduate who came to Israel, Jerusalem specifically, as a spiritual quest. I lied. While I identify as Christian, sometimes, I was not there as a pilgrimage to the Holy Land because I view illegally partitioned land as defiled. I was there to visit Palestine but feared that the announcement of my truth would have not set me free. After discovering that I was Christian, and therefore not Muslim, my reason for being there and my writings were no longer an issue, and I was unconstrained. But my words as in my thoughts as in my affect as in my voice were not–that is not until her words found me.

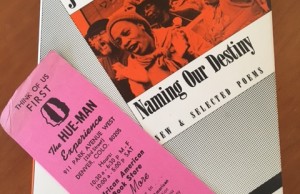

Black feminist poet warrior scholar June Jordan traveled with me from my apartment in Bedstuy (or Bedford-Stuyvesant as she named the urban neighborhood in Brooklyn that she also called home) to Tel Aviv, West Jerusalem, and Ramallah…from Dheisheh Refugee Camp, Beit Lehem, and Qalandia Checkpoint. June Jordan’s spirit was present when I traveled in utter silence with tears escaping my eyes in the dark of the night as I listened to a Palestinian elder, Abu Hussam, tell stories of his childhood as he pointed to acres of barren land that was once the village, his village, of Lajun. The aged laminated map that he held tightly in his hands evidenced his truth and memorized the roadways, the homes, and the wells that Al Nakba sought to dis-remember. The elder held back his tears. I let mine flow. And, as I listened, I opened my internet browser on my iPhone in search of June Jordan’s words. She spoke to me:

-from Moving Towards Home

“Where is Abu Fadi,” she wailed.

“Who will bring me my loved one?”

New York Times, 9/20/82

(after the 1982 Phalangist/Israeli Massacre of Palestinian Refugees in Sabra and Shatila)I do not wish to speak about the bulldozer and the

red dirt

not quite covering all of the arms and legs

because I do not wish to speak about unspeakable events

that must follow from those who dare

“to purify” a people

those who dare

“to exterminate” a people

those who dare

to describe human beings as “beasts with two legs”

those who dare

“to mop up”

“to tighten the noose”

“to step up the military pressure”

“to ring around” civilian streets with tanks

those who dare

to close the universities

to abolish the press

to kill the elected representatives

of the people who refuse to be purified

those are the ones from whom we must redeem

the words of our beginning

because I need to speak about home

Like Jordan,

I did not wish to speak about aged maps

held tightly

like treasures in matured Palestinian hands

because they possess memories of dirt, of grass, of homes, of wells

exploded like dreams of return

because of the want for more “holy” land

that is defiled by blood, by tears, by debris, by bodies,

by 760 kilometers of separation wall

by many barb wired gates

by over 700 checkpoints

by newly paved roads graciously funded by USAID

guarded by young Israeli soldiers

trained to interrogate

armed with a smile

armed ready to secure land and rights

armed with guns

because everyone else are terrorists

whose anger can only be quenched by bloodlust

whose words are dangerous

because those are the ones from whom we must redeem

the words of our ending

because I need to speak about what was once home

My words my thought my affect my voice were dislocated from the grasp of fear and I began to write.

June Jordan’s words ( I was born a Black woman / and now / I am become a Palestinian) resuscitated my courage and like her I had become a Palestinian, though, I had been a Palestinian all along–even before my arrival on the land. I only needed to recall the guard that awaited me when I departed the plane; the guard that took my passport, my itinerary, my scrapbook, my words; the guard that interrogated me one on one in the security room wanting to know if my beard was a sign for allegiance to Allah…the many guards that guard a nation from everyone else but itself.

I am no longer silent because I refuse to become a “map” held in someone else’s hand carrying unvoiced memories.

I speak. I write. Because, I have to.

Pingback: Liberal Zionist Bingo « KADAITCHA

Pingback: Liberal Zionist Bingo « KADAITCHA

Pingback: Liberal Zionist Bingo « KADAITCHA

Pingback: Liberal Zionist Bingo « KADAITCHA