Talking Vultures, Humans, and Warm Flesh with Charles Bowden

By Alice Driver

Some people we know only through their words. And so it was with author Charles Bowden and his images of bloated bodies, scurrying rats, of air so hot that a single match would light it on fire, images of savagery inverted into beauty that came with the uncomfortable awareness of the nature of the human condition.

I came across Bowden academically when I was researching feminicide and violence against women for my Ph.D. I first came to know his work through the photoessay Juárez: The Laboratory of Our Future (1998), which included a preface by Noam Chomsky and an afterward by Uruguayan Eduardo Galeano as well as photos taken by photographers from Ciudad Juárez. The book depicted not only the physical violence that has so come to characterize Ciudad Juárez, but also the economic violence that precedes it, the violence of free trade and lax labor laws, the violence of houses made of cardboard, the violence of what is left unsaid and undone. Later, even though I disliked the sensationalist title, I read Murder City: Ciudad Juárez and the Global Economy’s New Killing Fields (2010) and then Dreamland: The Way Out of Juárez (2010),a collaboration Bowden produced with artist Alice Leora Briggs.

I had mixed feelings. I wanted to talk to the author.

The hummingbirds are hitting about half a gallon a day, he wrote to me in April. He signed the email chuck and wrote almost exclusively in lowercase letters. “Greedy little buggers,” I thought as I wrote him back requesting a date for an interview. I pursued him doggedly because I wanted to talk to him about his photoessay, Juárez: The Laboratory of Our Future, and, deep down, because there were certain gritty reversals of the universe in his language that I wanted to understand.

On another level, I was critical of his use of the term feminicide and the way he described women in his work. In Juárez: The Laboratory of Our Future he said, “I want to know about over there. I want to know the smell of the streets at 2 A.M., the taste of the whore under the streetlight, the greasy feel of the juice rolling down my chin from the taco bought at a stand near dawn.” The taste of a whore under the streetlight? I wanted to interview him and ask him about that.

It was always my intention to conduct the interview in person, but a slew of emails over a period of months produced no certainty about a time or place. When I was in Las Cruces, New Mexico for research, I contacted him because I knew he lived somewhere in the area. He told me that he lived six hours away, that he was not worth it, that the interview was not worth it. Let me decide that, I wanted to say.

In August, no interview was arranged, but he wrote, basically i am a slave to hummingbirds here. they are guzzling a half gallon a day now and this will soon explode as the leading edge of the fall migration arrives. In the meantime, while I waited, I continued to research his work. One day, after hearing him on the radio, I wrote to him impulsively. “I listened to your narration of the Creel massacre in Mexico. Your deep, gravely voice has a certain power all its own. I am envisioning a GPS system narrated by you.” After I sent the email, I panicked, felt unprofessional; I worried that he would never grant me an interview. A few hours later, Chuck responded, I think such a GPS system would cause wrecks.

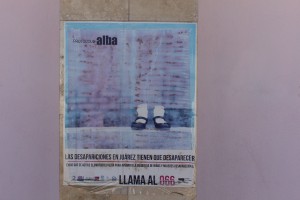

Photo by author: A poster posted near the monument to victims of feminicide urging an end to the disappearance of women

In the end, after almost a year of correspondence, there he was: peering at me through Skype, his weathered face half-cloaked in darkness. His voice was rough like sandpaper, so deep and resonant I felt as if he had returned from the dead to speak to me.

Bowden: I just came in the door. I’ve been sitting outside watching hummingbirds for three hours.

Driver: Hummingbirds appear a lot in Juárez: The Laboratory of Our Future.

Bowden: Well, I’m a birdwatcher. I’ve been spending my summers the last few years in one of the hotspots in the United States, in Patagonia, Arizona.

Driver: I’m not familiar with that area.

Bowden: The good news is very few people are. This afternoon the Rufous [hummingbirds] returned from their migration to Alaska, and I started seeing Plain-capped Starthroats which are found almost nowhere in the United States. For a birder, hell, this is like a hit of cocaine or something. It’s an odd pastime. You look at a bird, identify it, and feel like you’re a better person. I knew something was going on because I’ve been going through one and a half quarts of sugar water a day and suddenly it leapt to three quarts and then today to four quarts. Can you hear me all right?

Driver: Yes.

Bowden: Ok, God help you then. I start speeches that way. I ask the audience if they can hear me, and they all say “yes.” Then I say: “I’m sorry.” They relax.

Driver: It’s always good to begin with humor.

Bowden: You should diminish yourself to relax an audience. It’s self-deprecation. I think that because of our culture we all have this terror that we’re back in church and there’s some moron up in the pulpit, and we don’t like reliving that experience. I certainly don’t. I never have to do this with birds. They never look up to you.

Driver: They don’t require any maintenance.

Bowden: No, I feed ravens here and vultures.

Driver: Vultures?

Bowden: Yes, they roost across the creek, and I throw out bones and tripe every few days. I sit there with coffee, and they all gather around. It’s like a little coven of black birds.

Driver: That’s a bit of a dark pastime.

Bowden: Actually it’s not. I’ve lived with vultures. Ravens are super. Everybody that spends time around them becomes enamored of their incredible intelligence and sense of mischief. Vultures live in family groups, and are extremely benign. It’s like knowing a bunch of Quakers. They get this awful reputation because they share a trait with human beings — they eat dead things after they get warm.

Driver: That’s true.

Bowden: You know their bodies can’t really break down the tissue and so it rots a little. We turn on the oven. It’s the same reason. They’re very friendly. They live in a hierarchy. I once was at a desert water hole sixty miles from anywhere (Christ, they’re coming in to roost now) and they spent a week living about twenty-five yards from me disassembling a coyote. Every day they’d show up at the water hole at the same time, and they’d all line up like penguins to drink in this pecking order, and then they’d go back to the coyote. After a while, you know, we were just like neighbors. I got to observe them up close. It’s not a full-time job being a vulture. It’s not like they work all day. They spend a lot of time playing with each other and shooting the shit. Then I had the same experience with rattlesnakes.

The interview continued, and we left behind the vultures for the contested territories of defining a term that he didn’t believe in but I did: feminicide. What is feminicide? On a basic level, feminicide is used to define violence against women, a term that encompasses the institutional and cultural structures that contribute to violence against women and violence against the feminine, including transgender and transvestite populations. However, in the mainstream media and the academic world, the terms femicide and feminicide are used interchangeably, and not many people seem to agree on a definition. Some think that feminicide is used to describe the murder of any woman, and they argue that often women are killed in accidents or in random violence, and that the violence is not related to their gender or their performance of gender.

Was the term useful, or wasn’t it? Should it be a legal term, punished by the law? I argued that is was, and I thought about how some of the murdered women in Ciudad Juárez were raped, were accused of being prostitutes, were judged for wearing red fingernail polish or a lacy bra, or were told that their daughter wasn’t missing or dead, that she had just “run off with a boyfriend.” I knew that men experienced extreme violence, but I doubted that it took the same form, that the social and cultural fabric of society judged them in the same way. Chuck didn’t find the term feminicide useful, said it didn’t help understand violence in such a complicated city. But he also admitted he didn’t find the term hate crime to be useful.

With the discussion of feminicide, the interview took on the distinct feel of a physical fight, as if he and I had taken up swords and were locked in a match of force. He argued that since more men died than women overall, the discussion of violence against women overwhelmed and ignored the deaths of the men. For a moment, I mistook force for anger, and thought I would be crushed like a firefly between the fingers of a grubby kid.

However, the verbal heat was not a manifestation of any emotion, not an affront to me personally, and Chuck was no grubby kid. I was afraid, but in one bold flash I asked him about the taste of whores under the streetlight. In response to my questions about his use of language he replied, “Do you think when Emerson wrote ‘Brahma’ and ‘I turn and pass and kill again’ that he wanted to know about killing?” Bowden used Emerson’s quotation as an example of how a writer has poetic license within his work and should not necessarily be interpreted literally.

Two things stayed with me from the interview: the idea that fierce verbal sparring implies respect and not anger, and his comment about the similarities between vultures and humans.

Now and then, after the interview, I would send Chuck pieces of my writing, an email into the black hole of cyberspace. As a struggling writer, I knew how hard it was to be everything, to capture all sides of a story, and I wanted to forgive him for being a cowboy, for interviewing assassins, for leaving women on the blurred edges of his stories. There was always the fear that I was not allowed to have both feelings, that in respect there was no room for doubt.

Doubt. It reminds me of the first time I saw a photograph of what I thought was a Mexico City street covered in used condoms. Good god, how that image struck me. And how sad and angry I felt when I walked that street and discovered that the condoms were actually hundreds of flattened bottle caps. But, I thought, that is where life is, in those cracks in between what we believe and what we find to be true. And so I dug into my doubt. I wanted to keep chipping away at our discussion of feminicide, to break through the hard exterior of his stance and find a place of discussion where we could work out why it was or was not a valid term.

I sent him a story I wrote about La Merced in Mexico City because it explored the dark territories he seemed to inhabit. And he wrote back with a memory that resonated with me as if it were my own: it is a long time since i’ve been to that grim market and i am sorry to learn things have not changed much. you certainly know more about the place than i ever did. i still remember a prostitute standing on the edge of the market and a rat that seemed the size of a cat standing nearby. it was afternoon and there was that din that is the white noise of Mexico City. for some reason the woman and the rat are frozen in time in my head as is the golden light.

But it was strange, and I wondered why I thought his vision was “my own.” It had nothing to do with the streets I walked, their walls spray-painted with leaping purple deer. It had no relation to the heat of bodies, the kids who wrapped their arms around me and wished my family well, the espresso and foamed milk I drank in la Aguilita. Chuck’s voice was strong, picking up the dirty rat and the stereotypical prostitute that defined La Merced from the outside and somehow making it beautiful. Those words drew me in, made me think they were like my own. But they were not and never would be. I began to wonder what I had learned from our interview, from what, as it turned out, was two years of sporadic correspondence about feminicide.

I wanted him to know that what stuck with me from the interview had little to do with our academic discussion of his photoessay Juárez: The Laboratory of Our Future. Vultures are like Quakers. Vultures are like humans. In those few short minutes of conversation before our interview began, he inverted one small universe, freeing the vulture from its long-standing function as a symbol of death and at the same time reminding me that what we find so barbaric in vultures is actually a central human practice.

A few days later, Chuck wrote me back to make one correction: there is one error on my part—i did not see a plain-capped starthroat. i was wrong. i checked later with a local bird wizard and alas learned of yet one more instance of my ignorance. so scratch that reference lest we mislead the ornithological universe.

I thought that correspondence was a fitting closure. But we continued to go back and forth about femicide/feminicide. He wrote, i think in the end my problem with the use of the word femicide is that the people using it in the case of juárez often use false numbers and also ignore other realities there—poverty, corruption, US slave factories and of course the fact that 90 percent of the dead are males and that what we have is social breakdown and gender is not the best tool for looking at it. but i have i hope retired from such matters since i have noticed that it is like Israel–anyone who questions the matter gets an ad hominem attack. and to me such attacks are a waste of time and thought. and not the way to learn. ah, off to the cranes and their dances.

Photo by author: 2010 in Lomas de Poleo, an area where many bodies of feminicide victims were found in the 1990s

I thought about the cranes, about hummingbirds, about the need to find some source of peace while writing about violence, and then I wrote back, “To me feminicide is a framework for discussing issues related to gender and the performance of gender, issues that do exist and affect women, transvestites, and transsexuals differently than men. Issues of domestic violence, rape, and the way institutions in Mexico treat women (they treat men perhaps equally bad, but the kind of treatment is not the same) exist and should be discussed. The attacks on both sides of the feminicide debate are equally strong. People say that feminicide researchers are ‘profiting’ from ‘yet another book’ which seems a bit much to me. Anyone researching or writing about that kind of violence deals with so much depressing stuff and certainly does not make any money. Yes, best to be with the birds and in nature.”

okay. as someone who covered sex crimes for three years, i don’t see the area as one of profit but one of misery. i certainly didn’t like my time dealing with it. but i think we are back to the beginning. i don’t find femicide a useful term when i look at the carnage but i am willing to be persuaded. i don’t find the term hate crime that useful either but now it is a matter of law. as for the birds. yes they have always helped. i became a birdwatcher when i began covering murders as way to stay sane.

And he was willing to be persuaded, and I wondered if that was enough for me. What had I been searching for, reaching for, trying to grasp? It went beyond feminicide, beyond the violence I watched in films and on TV in Mexico, beyond the violence I read and reread in Roberto Bolaño’s vóragine of a novel 2666, beyond the bodies that sometimes invaded my dreams. I wanted to believe that violence could be defined, categorized, and punished, but I also wanted to believe in the imperfect writer, the writer who lived and fought and survived on his voice, on his words, on some dark rat and some sad prostitute bathed in a light that almost made them beautiful.

__________________________________________

Alice Driver works on a short film project on the Mexican side of the border wall near the international crossing Santa Teresa, New Mexico. Copyright © 2013 by Julian Cardona.

Alice Driver is a postdoctoral fellow at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, where she conducts research on feminicide and the representation of violence in Mexico in literature, film, and cultural studies at the Centro de Investigaciones sobre América del Norte. Her book proposal, “More or Less Dead: Feminicide, Haunting, and the Ethics of Representation in Mexico,” was recently accepted by the University of Arizona Press. She is also a contributor at Women’s Media Center. For more information, visit her website.

8 Comments