COLLEGE FEMINISMS: Slamming the Door: An Analysis of Elsa (Frozen)

By Shira Feder

The Disney Princess franchise presents misogynist and terrifying fairy tales for profit. These stories enforce patriarchal views towards women that instate an impossible standard of beauty in the young female characters who serve as role models for children. Disney has failed to represent women of color as princesses despite the recent inclusion of Tiana from The Princess and the Frog into Disney’s line of aggressively marketed iconography. Even with this inclusion, the racial representation is problematic because Disney princesses continue to be presented as stereotypically inadequate regardless of incorporating racial difference.

The Disney Princesses possess little agency. They sacrifice integral parts of themselves for men (for example, the loss of voice in The Little Mermaid), are forced to work for ‘evil’ stepmothers for years (Cinderella and Snow White), and are featured in only seventeen minutes of the movie named after them (Sleeping Beauty). While there are exceptions to this rule, the majority of the princesses are presented as lacking any vision of themselves without a man to provide it for them.

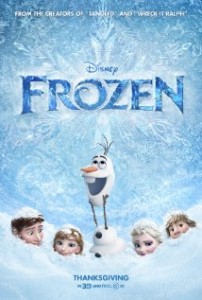

However, in the most recent film, Frozen, Disney seems to have heeded some of these gendered critiques. Frozen subverts these ubiquitous tropes with its main characters, Anna and Elsa, who—despite physically fitting the profile of classic Disney princesses by being white, rich, and shockingly thin—display agency in ways that past princesses have not. Anna embarks on a dangerous quest to find her sister when Elsa’s prodigious powers get out of control and, ultimately, the kingdom is saved though the true love of her sister rather than her suitor. This is the first Disney film in which a princess makes an egregious error that negatively affects everyone around her—Elsa freezes her kingdom—but is still able to receive forgiveness and respect by the end of the movie.

tropes with its main characters, Anna and Elsa, who—despite physically fitting the profile of classic Disney princesses by being white, rich, and shockingly thin—display agency in ways that past princesses have not. Anna embarks on a dangerous quest to find her sister when Elsa’s prodigious powers get out of control and, ultimately, the kingdom is saved though the true love of her sister rather than her suitor. This is the first Disney film in which a princess makes an egregious error that negatively affects everyone around her—Elsa freezes her kingdom—but is still able to receive forgiveness and respect by the end of the movie.

Elsa is given opportunities to make mistakes that Disney Princesses have not been given in the past. Elsa often feels threatened, codes the world as black and white, and runs into trouble a number of times because of her ambiguous moral compass. Elsa shows herself as willing to murder to protect her heightened sense of self-preservation, and judging from the look of shock on her face every time she loses control, she is clearly more prone to violence than she thinks. Abandoning one’s throne is the highest level of treason a monarch can commit and Elsa does this at the first provocation—she chooses herself over her kingdom and refuses to  explain. Moreover, Elsa threatens Anna’s life when she creates her snow monster and appears to have no qualms about killing people that have come to retrieve her. Even when she realizes the consequences of her actions, she still refuses to go back to Arendelle until she is brought back in chains. Elsa is a Hero Antagonist, an ultimate heroic character that inadvertently provides obstacles the protagonist must overcome before the movie can end happily-ever-after. Elsa remains a hero because she chooses to make the difficult choice of continuing to lock herself away, even when her parents are no longer present, to protect the people she loves. Her redeeming quality is her unwavering desire to protect her loved ones even when it comes at the cost of her quality of life.

explain. Moreover, Elsa threatens Anna’s life when she creates her snow monster and appears to have no qualms about killing people that have come to retrieve her. Even when she realizes the consequences of her actions, she still refuses to go back to Arendelle until she is brought back in chains. Elsa is a Hero Antagonist, an ultimate heroic character that inadvertently provides obstacles the protagonist must overcome before the movie can end happily-ever-after. Elsa remains a hero because she chooses to make the difficult choice of continuing to lock herself away, even when her parents are no longer present, to protect the people she loves. Her redeeming quality is her unwavering desire to protect her loved ones even when it comes at the cost of her quality of life.

Unlike most Disney Princess movies where the princess undergoes a transformation in the movie that positions her to be less than she was before—Ariel from a singing mermaid to a mute human, or Cinderella from a hopeful maid to a woman whose true love danced with her all evening yet cannot remember her face, or Sleeping Beauty and Snow White who are actual cadavers, literally lacking life force – Elsa transforms into an adult, ready to have an active role in her own life, in full control of her powers. This transformation takes place in a self-preserved prison created by stigmatism and fear—a setting that prompts valuable questions for Disney.

Why must there always be some form of prison, some literal or figurative manifestation of the distance society places between itself and the people who did not mold themselves in its image? Why must women always be presented as locked up in a prison of their own making, despite possessing the key to its doors?

The existence of the prison as an omnipresent metaphor and narrative trope is more telling of society’s flaws than Disney’s presentation of it. Elsa frees herself from her prison and defies another narrative trope – the princess in need of a prince to rescue her. While this movie does not question the existence of the prison, it does take an unexpected leap away from male savior-hood.

Additionally, Elsa appears to be the first Disney Princess to acknowledge the issue of mental health as a reality for women. At Elsa’s coronation, her hands are shaking violently, prompted by the fight or flight’ response in the body in response to life threatening issues. Many people who suffer from anxiety disorders view innocuous occasions as life threatening and suffer from shaking limbs as a result. Also, when Anna and Elsa finally reunite, Elsa appears to be suffering from extreme guilt and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, haunted by the fact that she nearly killed her sister. This reaction is triggered by Anna herself, as is apparent from the Elsa’s flashback to this event and instinctual flight from the room. There are also symptoms of an uncontrolled panic attack present here. Elsa’s powers are beyond her control once she becomes agitated; her singing becomes more and more incoherent until it is nothing but a shout (“I can’t!”) despite Anna’s evident sympathy and logical pleas. There is a pervasive tendency in US culture to view people suffering from mental illness as weak, lazy, inadequate, or lacking control. Creating a Disney princess who happens to have an anxiety disorder is a progressive step towards creating characters that accurately represent our world. Elsa is not portrayed as selfish or “crazy,” but as someone who is doing the best she can in her situation.

Importantly, Elsa challenges the prevalent “good girl complex,” a term designated to describe the pressure girls are under to be perfect in all areas. In her song, “Let It Go,” Elsa sings “that perfect girl is gone.” She refers to the pressure of having to be the perfect daughter, sister, and princess. In this song, Elsa releases herself from these pressures and allows herself the freedom to make mistakes and live how she chooses. Elsa also challenges the virgin/whore dichotomy. When Elsa changes into a more overtly sexy outfit and looks directly at the camera with a raised eyebrow, it appears that she is a young woman coming to terms with her sexuality and she does not care what anyone thinks. She slams the door in the audience’s face, indicating that she needs privacy to understand herself or that the audience does not have to be present for her sexual awakening. This defies the fetishizing of young women for audience consumption.

Elsa can be embraced as a symbol of sexual empowerment and challenging norms of sexuality. There is ample space for interpretation of Elsa’s sexuality in this film. The parallels between Elsa’s powers that challenge the people around her, her own understanding of herself, and the process of “coming out” are significant to see in a Disney film. Like many people coming to terms with themselves, Elsa must grapple with accepting her immense powers, which have been stigmatized by her society as negative. The movie gives us no reason to believe that anyone, except Elsa herself, ever doubted that she could easily remove the ice. What Elsa feared about herself was what made her different, powerful, and special. The characters’ acceptance of Elsa’s powers reflects a growing acceptance of multiple sexual orientations and gender formations in the US. There is increased visibility of gender difference and sexuality in popular culture (in forms such as LGBTQIAP TV characters, pride parades, and gay rights movements) and Elsa’s character can further contribute to these shifts. The Disney Princess is no longer hiding in a castle.

What does the creation of a complex and contentious heroine mean for the future of Disney Princess films?

Elsa’s messy, complicated balancing act between selflessness and selfishness makes her a human being that the audience can understand and relate to—she is not just a fairytale. Elsa’s struggle to accept her tremendous powers is a feminist one because Elsa, like many young woman today, was raised to see her strengths as weaknesses. If a woman is authoritative, she is considered bossy. If a woman is strong, she is considered unfeminine. If a Disney Princess possesses unprecedented powers it was considered dangerous. Here Disney perhaps unintentionally challenges the invisible limits of what a woman can handle and suggests that there may be none. Elsa presents Disney Princesses as fallible, accessible, and relatable, which is crucial for thinking about how the figure of a princess can be a feminist role model for children. This complex, nuanced character has raised the bar for the creation of all future princesses because Elsa teaches girls to embrace their strengths and differences in all varieties and forms. Although Disney’s version of feminism is still flawed, creating female characters that have agency and strong characteristics is a big step forward and away from the presentations of princesses as agentless young women.

Reconciling Elsa’s idiosyncrasies, confusions, contradictions, and indiscriminate treatment of the people around her with the two dimensional caricatures of yore is no longer possible. Frozen suggests that the power dynamics of sexuality, gender, and race are shifting and needing to shift within Disney Princess films. Because Frozen differentiates itself from past princess films and slams the door on the concepts of “perfect princess,” superficial romance, needing a prince, and the morally perfect hero, we are able to rethink female role models within popular culture. It is important to consider how Elsa transcends the previous princess character by daring to slam the door in the audience’s perceptions of her. By acknowledging her flaws and embracing her differences, the Disney Princess franchise has changed.

Reconciling Elsa’s idiosyncrasies, confusions, contradictions, and indiscriminate treatment of the people around her with the two dimensional caricatures of yore is no longer possible. Frozen suggests that the power dynamics of sexuality, gender, and race are shifting and needing to shift within Disney Princess films. Because Frozen differentiates itself from past princess films and slams the door on the concepts of “perfect princess,” superficial romance, needing a prince, and the morally perfect hero, we are able to rethink female role models within popular culture. It is important to consider how Elsa transcends the previous princess character by daring to slam the door in the audience’s perceptions of her. By acknowledging her flaws and embracing her differences, the Disney Princess franchise has changed.

The upcoming Disney film, Moana, gives us a glimpse into Disney’s continued progressive modus operandi. In 2018, Disney is scheduled to release, Moana, which is about a native Hawaiian ocean explorer. The motivations for this may be simply fiscal, but maybe Disney will explicitly engage with histories of colonization. The result of Disney’s progressive agenda on children is one that cannot be underestimated. Disney is redesigning their characters to present a more diverse, tolerant mirror of our current world. Multicultural inclusion, the validation of mental health issues, sexual freedoms, and the importance of personal agency for all are concepts that twenty years from now may be familiar to children who grow up with these third generation Disney films. There is continued potential for change.

************************************

2 Comments