“Hands Up! Don’t Shoot!”: Gesture, Choreography, and Protest in Ferguson

By Anusha Kedhar

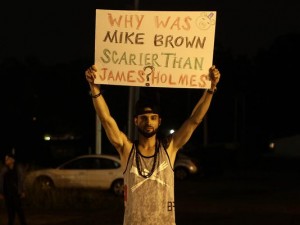

By now, you know this phrase well. It has become the rallying cry of those protesting the murder of Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Missouri earlier this year. Like other memorable activist slogans—such as “Hell no! We won’t go!” “What do we want? Freedom! When do we want it? Now!” “No justice? No peace!”—it captures the essence of collective anger in response to injustice.

Unlike other slogans, though, “Hands up! Don’t shoot!” is not just voiced. It is also embodied. Contained within the phrase is both a plea not to shoot, as well as the bodily imperative to lift one’s hands up. Since Michael Brown’s murder, we’ve seen photos of young black men and women in Ferguson, Tibetan monks from India, black Harvard law students, school children in Missouri, young people in Moscow, and a church congregation in New York City with their hands up. Some stand, some kneel, some bend their heads, some stare straight ahead. Each one symbolizes a bodily act of solidarity with Michael Brown and victims of oppression of state-over-citizen around the world. As Matt Pearce comments, the hands up gesture “has been transformed into a different kind of weapon.”

What does this gesture mean for the different bodies that enact it? How do protesters assign new meanings to such a codified bodily gesture? How can we read these protests as choreographic tactics and gestures of resistance? Why is the deployment of the body in the case of the Ferguson protests so significant?

I want to offer five ways of reading this gesture in the following list, which is by no means exhaustive:

1. A Habitus: Arms rise and extend high in the air to reveal open, empty, unarmed palms. A silent scream, this gesture pleads with its spectator: I am innocent. I am unarmed. I am not a threat. I surrender. I submit. Submission and fear have become embedded in the black body, a part of its daily habitus. According to Loïc Wacquant, habitus, a term attributed to Pierre Bourdieu, is “the way society becomes deposited in persons in the form of lasting dispositions, or trained capacities and structured propensities to think, feel and act in determinant ways, which then guide them.” Young black men and women in the U.S. learn this gesture of surrender and submission early on when dealing with police. Black parents teach their children that if they get pulled over, for example, they should move slowly and deliberately and dictate their actions to the officer, offering a kind of play-by-play of their body’s movements. I am unfastening my seat belt. I am reaching into the glove compartment. I am handing you my registration. In a society where the presence of black bodies in public spaces is seen as de facto threatening, unruly, and “out of place,” black men and women are forced to justify their everyday movements, to make their bodies legible to structures and institutions of power. Even the body’s most mundane actions—walking home in the case of Michael Brown or Trayvon Martin, knocking on someone’s door in the case of Renisha McBride, or adjusting a waistband in the case of Kimani Gray—are questioned, challenged, and deemed suspicious. Through repeated enactments, the hands up don’t shoot gesture has become part of the black body’s repertoire of survival.

1. A Habitus: Arms rise and extend high in the air to reveal open, empty, unarmed palms. A silent scream, this gesture pleads with its spectator: I am innocent. I am unarmed. I am not a threat. I surrender. I submit. Submission and fear have become embedded in the black body, a part of its daily habitus. According to Loïc Wacquant, habitus, a term attributed to Pierre Bourdieu, is “the way society becomes deposited in persons in the form of lasting dispositions, or trained capacities and structured propensities to think, feel and act in determinant ways, which then guide them.” Young black men and women in the U.S. learn this gesture of surrender and submission early on when dealing with police. Black parents teach their children that if they get pulled over, for example, they should move slowly and deliberately and dictate their actions to the officer, offering a kind of play-by-play of their body’s movements. I am unfastening my seat belt. I am reaching into the glove compartment. I am handing you my registration. In a society where the presence of black bodies in public spaces is seen as de facto threatening, unruly, and “out of place,” black men and women are forced to justify their everyday movements, to make their bodies legible to structures and institutions of power. Even the body’s most mundane actions—walking home in the case of Michael Brown or Trayvon Martin, knocking on someone’s door in the case of Renisha McBride, or adjusting a waistband in the case of Kimani Gray—are questioned, challenged, and deemed suspicious. Through repeated enactments, the hands up don’t shoot gesture has become part of the black body’s repertoire of survival.

2. A Failed Sign: What happens when this universal sign is not respected? When this bodily act of submission is not seen or heard? Michael Brown’s sign of surrender was willfully ignored by police officer Darren Wilson. Brown’s hands up don’t shoot gesture failed to communicate across the chasm between state and citizen, officer and subject, white and black. As keguro notes, Michael Brown’s murder “indexes the failure of this bodily vernacular when performed by a black body, a killable body […] Blackness becomes the break in this global bodily vernacular, the error that makes this bodily action illegible, the disposability that renders the gesture irrelevant. [It is read as] always already threatening, even when that movement says, ‘I surrender.’” In short, blackness is what lays bare the limits of this kinesthetic sign, what turns this universal gesture of submission into a gesture of guilt, criminality, and culpability. This bodily act was supposed to signify surrender, but it failed. It could not save Michael Brown.

2. A Failed Sign: What happens when this universal sign is not respected? When this bodily act of submission is not seen or heard? Michael Brown’s sign of surrender was willfully ignored by police officer Darren Wilson. Brown’s hands up don’t shoot gesture failed to communicate across the chasm between state and citizen, officer and subject, white and black. As keguro notes, Michael Brown’s murder “indexes the failure of this bodily vernacular when performed by a black body, a killable body […] Blackness becomes the break in this global bodily vernacular, the error that makes this bodily action illegible, the disposability that renders the gesture irrelevant. [It is read as] always already threatening, even when that movement says, ‘I surrender.’” In short, blackness is what lays bare the limits of this kinesthetic sign, what turns this universal gesture of submission into a gesture of guilt, criminality, and culpability. This bodily act was supposed to signify surrender, but it failed. It could not save Michael Brown.

3. A Gesture of Innocence: Alive, blackness was all the “proof” Darren Wilson needed to ascertain Michael Brown’s guilt. He shot Michael Brown not once, not twice, but at least six times (presumably) in order to make sure “he was really dead.” My colleague Paul Buckley refers to this as the “overkilling of black bodies.” Now, in death, Michael Brown’s black skin must be opened up and turned inside out in order to prove his innocence. He must be repeatedly autopsied, sliced open not once, not twice, but three times in order to make sure “he was really innocent.” Were the bullet wounds to the top of his head not enough? Was the fact that he was unarmed not enough? Were the eyewitnesses who said he had his hands up and said don’t shoot not enough? The overkilling and over-autopsying of black bodies is not unrelated. If guilt is skin deep, then it follows that innocence can only be found under the skin. So, even in death, it is the black body that is charged with carrying the heavy and unrelenting burden of proof.

3. A Gesture of Innocence: Alive, blackness was all the “proof” Darren Wilson needed to ascertain Michael Brown’s guilt. He shot Michael Brown not once, not twice, but at least six times (presumably) in order to make sure “he was really dead.” My colleague Paul Buckley refers to this as the “overkilling of black bodies.” Now, in death, Michael Brown’s black skin must be opened up and turned inside out in order to prove his innocence. He must be repeatedly autopsied, sliced open not once, not twice, but three times in order to make sure “he was really innocent.” Were the bullet wounds to the top of his head not enough? Was the fact that he was unarmed not enough? Were the eyewitnesses who said he had his hands up and said don’t shoot not enough? The overkilling and over-autopsying of black bodies is not unrelated. If guilt is skin deep, then it follows that innocence can only be found under the skin. So, even in death, it is the black body that is charged with carrying the heavy and unrelenting burden of proof.

By raising their hands in the air, the protesters remind us over and over and over again that all the bodily proof we need of Michael Brown’s innocence is the position of his body when he died. The gesture reminds us that Michael Brown was shot while he was kneeling, with his head down and his arms up. It reminds us that the police violated the code not to shoot when a person’s hands are up. It reminds us that the black body is never presumed innocent moving in white spaces. That space itself is white.

The hands up don’t shoot slogan implores the protestor not only to stand in solidarity with Michael Brown by re-enacting his last movements, but also to empathize by embodying his final corporeal act of agency. As a collective gesture, it compels us to take note of and publicly acknowledge the bodily proof of Michael Brown’s innocence.

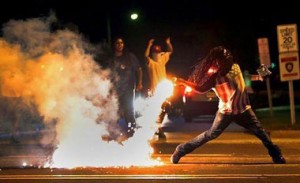

4. A Choreographic Tactic: As Susan Foster writes, protest is conceptualized either “as a practice that erupts out of a bodily anger over which there is no control” or “as a practice that uses the body only as an efficacious instrument that can assist in maximizing efficiency. Neither hypothesizes the body as an articulate signifying agent, and neither seriously considers the tactics implemented in the protest itself.” I suggest that analyzing the protests as choreographic tactics disrupts the popular, media-fed view of the Ferguson protesters as mobs of black bodies, which are unruly, lawless, and unpredictable. The actions of the protesters are carefully rehearsed and choreographed; they are intentional gestural acts deployed to protest the status quo and effect change. By protesting peacefully with hands up, they “refut[e] in the act of protest the stereotypes on which prejudice against them was rationalized.” While the bodies of protesters often “refuse to comply with the bodies of those in positions of authority,” in the case of the Ferguson protesters, it is actually through the ultimate and most recognizable gesture of cooperation that these protesting bodies tactically perform non-cooperation with an unjust and racist state.

4. A Choreographic Tactic: As Susan Foster writes, protest is conceptualized either “as a practice that erupts out of a bodily anger over which there is no control” or “as a practice that uses the body only as an efficacious instrument that can assist in maximizing efficiency. Neither hypothesizes the body as an articulate signifying agent, and neither seriously considers the tactics implemented in the protest itself.” I suggest that analyzing the protests as choreographic tactics disrupts the popular, media-fed view of the Ferguson protesters as mobs of black bodies, which are unruly, lawless, and unpredictable. The actions of the protesters are carefully rehearsed and choreographed; they are intentional gestural acts deployed to protest the status quo and effect change. By protesting peacefully with hands up, they “refut[e] in the act of protest the stereotypes on which prejudice against them was rationalized.” While the bodies of protesters often “refuse to comply with the bodies of those in positions of authority,” in the case of the Ferguson protesters, it is actually through the ultimate and most recognizable gesture of cooperation that these protesting bodies tactically perform non-cooperation with an unjust and racist state.

5. A Choreopolitics of Freedom: André Lepecki recently wrote about “choreopolicing” and “choreopolitics.” He defines choreopolitics as the choreography of protest, or even simply the freedom to move freely, which he claims is the ultimate expression of the political. He defines choreopolicing as the way in which “the police determines the space of circulation for protesters and ensures that everyone is in their permissible place”—imposing blockades, dispersing crowds, dragging bodies. The purpose of choreopolicing, he argues, is “to de-mobilize political action by means of implementing a certain kind of movement that prevents any formation and expression of the political.” Lepecki then asks what are the relations between political demonstrations as expressions of freedom, and police counter-moves as implementations of obedience? How do the choreopolitics of protest and the choreopolicing of the state interact?

5. A Choreopolitics of Freedom: André Lepecki recently wrote about “choreopolicing” and “choreopolitics.” He defines choreopolitics as the choreography of protest, or even simply the freedom to move freely, which he claims is the ultimate expression of the political. He defines choreopolicing as the way in which “the police determines the space of circulation for protesters and ensures that everyone is in their permissible place”—imposing blockades, dispersing crowds, dragging bodies. The purpose of choreopolicing, he argues, is “to de-mobilize political action by means of implementing a certain kind of movement that prevents any formation and expression of the political.” Lepecki then asks what are the relations between political demonstrations as expressions of freedom, and police counter-moves as implementations of obedience? How do the choreopolitics of protest and the choreopolicing of the state interact?

In Ferguson, we saw ample evidence of choreopolicing—police lined up in military like formations, charging suddenly or marching steadily forward like in battle, even their tactic of dispersing through the streets of Ferguson was a kind of choreographed chaos meant to break up groups and induce panic. If police formations and blockades in Ferguson are choreopolicing strategies of an increasingly militarized police force, the hands up don’t shoot gesture has become a choreopolitical tactic of defiance. Demonstrators walk towards police officers with their hands up, challenging the police officers to shoot, daring them to respond, to reckon with the officers’ culpability, to remind them of their culpability. The protesters’ movements defy structures of state power which restrict where, when, how, and with whom black bodies can move in public spaces. When young men like Michael Brown can be harassed and killed for walking in the middle of the street, the mere act of walking in a group through the streets of Ferguson constitutes an act of defiance, a choreopolitics of freedom.

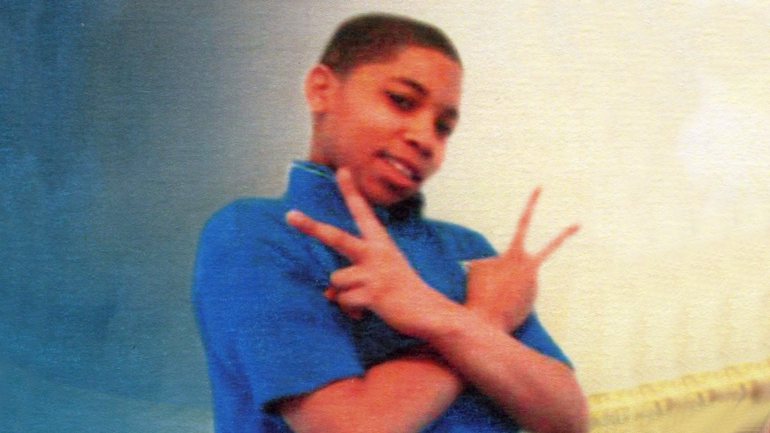

I want to come back to a question I posed earlier: Why is the deployment of the body in the case of the Ferguson protests so significant? The black body in the U.S. is seen as disposable, inhuman, valueless. The fact that police left Michael Brown’s dead body in the street for four hours is proof. As Charles P. Pierce points out, “Bodies do not lie in the street for four hours. Not in an advanced society. Bodies lie in the street for four hours in small countries where they have perpetual civil war […] Bodies are not left in the streets of leafy suburbs.” The bodily act of the hands up don’t shoot protests takes those same bodies that are surveilled, disciplined, controlled, and killed and infuses them with power and a voice. It resurrects those dead bodies left lying in the street, and asks us, compels us to confront the alive-ness of the black body as a force of power and resistance.

I want to come back to a question I posed earlier: Why is the deployment of the body in the case of the Ferguson protests so significant? The black body in the U.S. is seen as disposable, inhuman, valueless. The fact that police left Michael Brown’s dead body in the street for four hours is proof. As Charles P. Pierce points out, “Bodies do not lie in the street for four hours. Not in an advanced society. Bodies lie in the street for four hours in small countries where they have perpetual civil war […] Bodies are not left in the streets of leafy suburbs.” The bodily act of the hands up don’t shoot protests takes those same bodies that are surveilled, disciplined, controlled, and killed and infuses them with power and a voice. It resurrects those dead bodies left lying in the street, and asks us, compels us to confront the alive-ness of the black body as a force of power and resistance.

Lepecki argues that if to be political is the ability to move freely, then the ideal political subject is the ‘dancer.’ To me, the Ferguson protesters are quintessential dancers who, even in the most policed spaces, “the tightest of choreographic scores” as he so beautifully puts it, can transform a space of control, in which their movements are restricted, into a space of freedom, in which their movements are defiant, bold, and empowered a space in which they have the ability to move freely. With their hands up, the protesters reclaim a space for mobility for Michael Brown, for Trayvon Martin, for Eric Garner, for John Crawford, for Renisha McBride, for Yvette Smith, for Tarika Wilson and for all those named and unnamed black men and women who, in one way or another, raised their hands up and said ———.

Anusha Kedhar is an Assistant Professor of Dance at Colorado College. Her research looks at the intersection of race, transnational labor, global capitalism, and embodiment. She is currently working on an ethnographic book project which chronicles the lives of South Asian dancers in the UK and India and the effects of globalization on their bodies and bodily practices. She was a Fulbright Scholar to India in 2008 and was the recipient of the Selma Jeanne Cohen award by the Society of Dance History Scholars for excellence in dance scholarship in 2009. Anusha is also an established artist in the field of classical and contemporary Indian dance. She has been practicing Bharata Natyam for over thirty years, and has worked with some of the pioneers of contemporary Indian dance in the UK, including Subathra Subramaniam, Mayuri Boonham, Mavin Khoo, and Shobana Jeyasingh. Her own choreography has been presented on various international stages in London, Los Angeles, and Malta.

Pingback: Defiant Gestures | Theatre Room Asia

Pingback: Between The Lines - Kevin Alexander Gray: 'Ferguson October' Civil Disobedience Protests Target Police Violence in Communities of Color Nationwide |