Expectations: Intimate Feminisms Embodied

By Erin Durban-Albrecht and Monica J. Casper

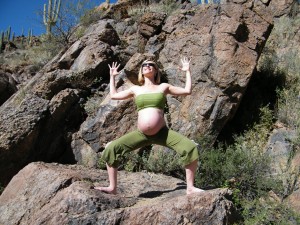

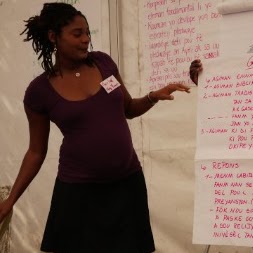

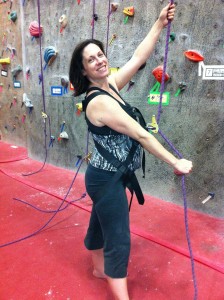

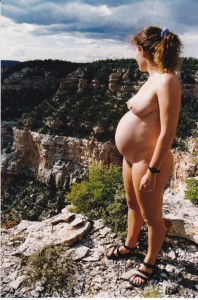

Our intention in collating this Mothers Day montage for The Feminist Wire is to celebrate women’s contributions to feminist social movements through creating and nourishing little people. More specifically, we want to make visible an important form of women’s reproductive work that is so often invisibilized—unless, of course, you are The Duchess of Cambridge or another celebrity mom.

We collected photos of pregnant women that not only celebrate the beautiful multiplicity of women, embodiment, and families, but that directly contravene the pervasive idea that motherhood doesn’t matter to feminism, or to feminist scholarship. This intimate archive was compiled by reaching out to feminist and womanist mothers (and fathers) in our lives—in person, on email, and via Facebook—and asking them to send us a photo of themselves when they were pregnant. The only parameter we gave them is that the photo needed to be one they really like of themselves. It did not matter to us if it was a selfie, a low-resolution snapshot taken by someone else, or a professional photograph. We both have photos of ourselves when we were pregnant that we planned on including.

While it turns out that many mamas were like us, a number of people did not have many options to choose from or, in some cases, any photos at all to include. They attributed the lack of documentation to being too busy and exhausted, being unpartnered, and/or—in most instances—just not liking their pregnant body (making work like Jade Beall’s A Beautiful Body Project all the more important). In two instances, all the photos of the women’s pregnancies were lost after being evicted from a storage unit and during the devastation of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. We also received several emails from graduate students who are about to enter the academic job market and do not want photos of themselves pregnant or with their children on the Internet, out of concern that it will effect people’s decisions about hiring them. This is certainly a well-founded fear.

We include this to acknowledge the various ways that this project is circumscribed by structural inequalities and pervasive patriarchal attitudes towards reproduction and women’s bodies. We also spoke with friends and colleagues who are not mothers (or who might be considered childless mothers), including those who have never been pregnant either by choice or circumstance. These women also perform all kinds of reproductive labor to care for other human beings, and this too goes unacknowledged. We wanted to open a space to recognize their experiences.

And of course, this wasn’t just about mothers, but about families. Our friends Matthew and Eric shared a photo of them with their son Gus, and also (with her permission) a picture of Gus’s birth mother, Taylor, taken during her pregnancy. She is Mama Taylor, and very much a part of their family. Because reproduction is multiple. Families are multiple. Love is multiple.

Erin…

The idea to create this montage of photos honoring the feminist and womanist work of reproduction came out of discussions that I, as someone new to parenting a baby in an academic setting, have had with Monica Casper, the head of my department and mother of two fabulous girls. Our exchanges have largely involved processing the fact that, as Monica states so succinctly, “pregnant women, mothering, and children—especially babies—are anathema to much of academia.”

I was aware of this reality since I have had many student and faculty friends with babies, small children, and other dependents, and I started my doctoral program as a parent of a teenager, which had its own challenges. Yet my experiences during pregnancy and in the year and a half that I have been carting my baby with me to teach, edit an academic journal, write my dissertation, attend meetings with my dissertation chair, participate in reading and writing groups, and present at academic conferences taught me in an embodied way that anti-mothering cultures and structures run deep in higher education, even in gender and women’s studies.

These problems stem from the systematic devaluation of women’s reproductive labor, and while they are not limited to academia, higher education is the professional field in the U.S. with the lowest percentage of women who are mothers, largely because of the ways that anti-mothering attitudes and practices continue to be sanctioned. While feminist and womanist activists have been working tirelessly to make changes on these fronts in the last half century, there is still so much that needs to be done to support women who want to have families.

Most of the women (and men) whose photos are included in the montage are students, teachers, professors, researchers, and/or people who work in educational settings. The women pictured here are our friends and colleagues who have shared with us their struggles, strategies, and accomplishments in terms of building a family while working in these contexts. Some of our struggles are particular to those spaces—such as being deemed “unprofessional.”

They also include being publicly ostracized for bringing babies/kids to class when child care is unaffordable or falls through, trying to plan pregnancies so that birth dates fall during the summer since there are no paid parental leave resources, losing funding because a project or degree requirements were not finished “on time” because the timeline does not take into account carrying and caring for children, limiting family size or being unable to conceive again because of the work demand of academic professional life and demands on the tenure clock, being denied tenure, having unimaginably hard birth and post-birth adjustment periods because of stress related to exams, finals, and dissertation defenses, and much, much more. (Scholars have written a plethora of books and articles about the various forms and effects of anti-mothering in the academy; for recent publications see Sekile Nzinga-Johnson 2013, Castañeda and Isgro 2013, and Ward and Wolf-Wendel 2012.)

We have also been variously effected by specific ideas about who should and should not reproduce that circulate outside of the academy as well. This manifests in being excluded, shamed, or treated unjustly for being perceived as too poor, too queer, too brown or black, too single, too foreign, too fat, too crazy, too sick/disabled, too young, too old, and/or just too unconventional to have children. In addition to struggles in the academy, some of us have to contend with the effects when our family constellations are not recognized by institutions we negotiate on a daily basis. Others battle legal systems that criminalize and forcibly separate our families.

All of us—though in stratified ways—are subject to the effects of neoliberalism that show up most virulently in discourses about an individual’s “choice” to reproduce that lets workplaces and other institutions off the hook of supporting women and children. That is to say, not only do different kinds of oppression shape our experiences of reproduction, but reproduction itself is a site where inequalities are produced.

Monica…

We titled this photomontage “Expectations,” in part to play on meanings of the word having to do with gendered expectations for women and in part to reference pregnancy. Of course, women are (and have long been) culturally expected to reproduce. One of my first dolls was a Baby Tender Love (now vintage), who peed into her diaper. Reproductive and mothering pedagogy started young, and it still does. Preconception care, about which I have written elsewhere (Casper and Moore 2009), only deepens this.

At the same time, I always knew I would have children; I wanted to be a mother, and specifically a mother to daughters (like my own mother was). This desire was not despite my feminism, but because of it. I viewed mothering not as a capitulation to social norms, but rather as a creative, political space in which to do good feminist works. I also viewed it as a love project, a journey to embark on within the broader context and circumstances of my life, including being a first-generation college student. At 19, I was unintentionally pregnant before I was ready to become a mother, and so chose an abortion. I also used birth control for years—and was using my diaphragm when I became pregnant during college.

Mothering two daughters, who are now 12 and 10, is without a doubt the hardest work I’ve ever done—and it’s also the most fulfilling. I say this not as a “hearth and home” conservative who would like to see women barefoot and pregnant (or in shackles), but rather as a lifelong feminist and a professional woman with a thriving career. I love to teach, to write, and to “do feminism” in its many incarnations. And yet, I love to mother. Not because it’s easy. And not because I am especially great at it. Indeed, I am daily reminded of my failings as a human being. Mothering challenges my expectations of myself, others’ expectations of me, my expectations of others, and the many assumptions I have ever held about being in control of…anything.

Mothering is very much life out of control, but in beautiful, unanticipated, provocative, affective, sometimes tragic, often joyful, embodied, and profoundly rich ways. And I love my children beyond measure in a way I love no other human beings. This is love, and it is feminism, and it is my life.

Yet lately, I have been thinking a great deal about the ways in which pregnant women, mothering, and children—especially babies—are anathema to so much of academia. I’m dismayed that so many feminist scholars perform a kind of epistemological and political exclusion—in the name of feminism and “theory”—that criminalizes motherhood as being out of bounds, improper, ontologically and politically suspect. I am especially curious that so many folks who study, for example, affect, power, and politics ignore, elide, and/or denigrate mothering (and women who mother), given that reproduction is such a potent site of meanings and interventions. The pregnant body, while a source of great pleasure and future life, is also a target for retrograde policies, racist and misogynist violence, and collective moralizing.

My scholarly work takes up issues of reproduction and has for more than twenty years. I need not repeat claims here about why reproduction matters, and why feminists (especially those concerned with race, gender, and power) should be paying attention to assaults on pregnant women and the reproductive body. But I do want to say this: Pregnancy matters. Mothering matters. Lives matter. Children matter. And all of this matters to feminism; to the ways in which we mobilize ourselves, others, our bodies, our loved ones, and our communities toward a better, more just world.

Works Cited

Casper, Monica J. and Lisa Jean Moore. 2009. Missing Bodies: The Politics of Visibility. New York: NYU Press.

Castañeda, Mari, and Kirsten Isgro, eds. 2013. Mothers in Academia. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Nzinga-Johnson, Sekile, ed. 2013. Laboring Positions: Black Women, Mothering, and the Academy. Toronto, ON: Demeter Press.

Ward, Kelly, and Lisa Wolf-Wendel. 2012. Academic Motherhood: How Faculty Manage Work and Family. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

A huge thank you to everyone who shared their beautiful photos with us: Amanda, Ariana, Audra, Corey, Darcy, Elise, Eric, Eve and Lisa, Gayle, Gus, Jesse, Jigna, Kelly, Leah, Leigh, Linda, Londie, Luz, Maïlé, Marlowe, Mary, Matthew, Megan, Robyn, and Taylor!

_________________________________________

Erin Durban-Albrecht is a queer, feminist activist and cultural worker living in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands who is inspired by participation in social justice movements as well as reading scholarship in critical ethnic studies, queer postcolonial theory, and transnational feminisms. Erin is also a Ph.D. candidate in gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona in the final stages of writing a dissertation, “Postcolonial Homophobia: United States Imperialism in Haiti and the Transnational Circulation of Antigay Sexual Politics,” that focuses on various transnational social movements—such as those for LGBTQI rights and those for neoconservativism—in postcolonial Haiti and its diaspora.

Erin Durban-Albrecht is a queer, feminist activist and cultural worker living in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands who is inspired by participation in social justice movements as well as reading scholarship in critical ethnic studies, queer postcolonial theory, and transnational feminisms. Erin is also a Ph.D. candidate in gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona in the final stages of writing a dissertation, “Postcolonial Homophobia: United States Imperialism in Haiti and the Transnational Circulation of Antigay Sexual Politics,” that focuses on various transnational social movements—such as those for LGBTQI rights and those for neoconservativism—in postcolonial Haiti and its diaspora.

Monica J. Casper is a managing editor of The Feminist Wire, Professor and Head of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona, and a scholar of reproduction, health, bodies, and trauma. She’s author of a stack of books and articles, but is most proud of being author of her children’s lives–lives that they are continually and necessarily rewriting on their own terms. She lives, loves, writes, and plays in Tucson. For more information, visit www.monicajcasper.com.

Monica J. Casper is a managing editor of The Feminist Wire, Professor and Head of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona, and a scholar of reproduction, health, bodies, and trauma. She’s author of a stack of books and articles, but is most proud of being author of her children’s lives–lives that they are continually and necessarily rewriting on their own terms. She lives, loves, writes, and plays in Tucson. For more information, visit www.monicajcasper.com.

1 Comment