Black Feminist Intellectual: A Conversation with Professor Imani Perry

DM: At present, you hold a primary appointment as a Professor within the Center for African American Studies and a secondary appointment in Law and Public Affairs at Princeton University. You hold a Ph.D. (Harvard University) and J.D. (Harvard Law), and your interdisciplinary research focuses on race and African American culture. You describe yourself as a Black feminist who was born in the South and who presently lives in a major northeast city. Can you give our readers the short version of your amazing journey?

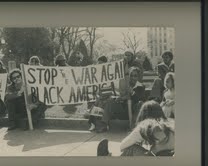

Imani as a little girl with her parents at a protest in Birmingham. The sign reads “Stop the War Against Black America.”

IP: It’s hard to make this short: I was born in Birmingham, Alabama into a large Black Catholic family nine years after the 16th street Baptist church bombing. I am the child of intellectuals and activists; the freedom movement was a constant theme in my coming of age. I moved North to Cambridge, Massachusetts at age 5 (after a brief time in Milwaukee where I attended a “freedom” pre-school that was built in response to a boycott of segregation in city schools.) In Cambridge, my mother began doctoral work again (she had been one of four Black women at Yale in the Theology and Philosophy program before I was born). I was educated at a progressive Quaker school and lived in a counter-culture, multi-racial environment. In the summers, I returned home to Alabama or visited my father in Chicago. My father lived in a gay community and was very active in social justice work around prisons and Central America. I attended camp at Jane Addams Hull House and the New City YMCA, which was a few blocks away from The Cabrini Green housing projects back then. Many of my fellow campers lived in Cabrini. Needless to say, I experienced a wide cross section of American life. I also had access to excellent schools, and my parents are both active scholars and people who have devoted their lives to trying to make a meaningful contribution to the world. It is unsurprising that I became an academic; although, until I was 19, I thought I was going to be a math professor. I attended Yale as an undergraduate student in the era when 3rd wave feminism was born there; the queer community was thriving and our expressions of Blackness were expansive. And I went into a Ph.D. program at Harvard in the “dream team” era in African American studies. I began Harvard Law School when Lani Guinier first joined the faculty. I was educated, and educated well, in an exciting time.

When I graduated, my first job was as a law professor at Rutgers Camden School of Law. I worked there for 7 years, earned tenure in my 5th year and was double promoted to full professor early. At Rutgers, I taught doctrinal courses like contracts and constitutional law but also taught critical race theory and a good deal of critical race feminism. After teaching a course in African American studies at Columbia and loving it, I decided I really wanted to teach in an interdisciplinary program. I’m now in my 4th year at Princeton, where I serve on the faculty in African American studies. I’m affiliated with other departments: Law and Public Affairs, Gender and Sexuality Studies, American Studies. And I also teach courses cross-listed with the Woodrow Wilson School and the Politics Department. What’s wonderful about that is that I meet students from across the University, and they work together to learn from the texts we read that come from a range of disciplines.

DM: You recently offered a compelling critique via social media in which you noted: “Black feminism used to be inherently radical, critical of classism, sexism, racism, heterosexism, and structures of domination, exploitation and imperialism everywhere. But now we have our own versions of NOW feminism, derivative 2nd wave feminism, and tone-deaf elitist middle class feminism.” Can you say more about these contemporary Black feminisms that you’ve named and why it might be important to remember the political and intellectual frameworks out of which Black feminisms emerged?

IP: Neoliberalism has infected every area of thought, even those we think of as inherently progressive. Feminism that is about “choice” (read consumption) rather than an analysis of power, and comes through the mechanisms, and reflects the priorities, of large corporations has very limited potential to actually say much of anything about the deep structure of inequality. I think it is important to remember early Black feminisms because those women had a deep analysis of inequality, one that began with, but extended far beyond their existences as Black women to address all forms of oppression at home and abroad. Those feminists did not celebrate the powerful, but rather advocated for the least of these. And their intellectual work was never simply about the fact of someone being born in a Brown skinned xx body, but rather about the interpretive power of beginning one’s thought from the experience of being Black and a girl or woman. I am worried when I read the title “Black feminism” applied to championing women like Susan Rice. I think a traditional and sophisticated Black feminist analysis does understand that she was targeted as a function of her race and gender; and yet, it also takes a critical posture towards her ideology which lies contrary to global principles of justice. Black feminist thought is not simply an interest group advocating for powerful Black women, it is about seeing the world with a vision of liberation. At least it should be.

IP: Neoliberalism has infected every area of thought, even those we think of as inherently progressive. Feminism that is about “choice” (read consumption) rather than an analysis of power, and comes through the mechanisms, and reflects the priorities, of large corporations has very limited potential to actually say much of anything about the deep structure of inequality. I think it is important to remember early Black feminisms because those women had a deep analysis of inequality, one that began with, but extended far beyond their existences as Black women to address all forms of oppression at home and abroad. Those feminists did not celebrate the powerful, but rather advocated for the least of these. And their intellectual work was never simply about the fact of someone being born in a Brown skinned xx body, but rather about the interpretive power of beginning one’s thought from the experience of being Black and a girl or woman. I am worried when I read the title “Black feminism” applied to championing women like Susan Rice. I think a traditional and sophisticated Black feminist analysis does understand that she was targeted as a function of her race and gender; and yet, it also takes a critical posture towards her ideology which lies contrary to global principles of justice. Black feminist thought is not simply an interest group advocating for powerful Black women, it is about seeing the world with a vision of liberation. At least it should be.

DM: If a shift has taken place, do you think it is possible to conceive Black feminisms that reach back–to recuperate and bring into the present—a tradition of intersectional analyses and radical praxis–and push forward–to rethink and extend analyses and political work in areas under-theorized and not yet explored?

IM: I am currently writing about gender, and I am absolutely trying to do that. I think many other scholars are as well: Sara Ahmed and Sharon Holland immediately come to mind. Moreover, a lot of the women of the generation before me (I’m 40 years old) are still thinking and writing, such as Patricia Hill Collins and Bonnie Thornton Dill. The issue is: how do we get young feminists to turn to the books and to the grassroots, as much as they turn to celebrity feminists and the non-profit industrial complex, for their intellectual and political development? There is nothing more macho than corporate power and empire, feminists ought to be immediately skeptical of both even as we have to engage with them if we live in the United States. I’m worried that not enough self-proclaimed feminists have that skepticism. Black queer studies is probably the most robust area right now, in that it is a field that remains explicitly political and deeply analytical, yet connected to the lives of ordinary people: I’m thinking of scholars like E. Patrick Johnson or Rinaldo Walcott, here. All that to say, I think exposing students to sophisticated ideas and modes of analysis will provide them with the tools to push us further. Young people will be at the vanguard of a revitalized intellectual movement for gender justice.

IM: I am currently writing about gender, and I am absolutely trying to do that. I think many other scholars are as well: Sara Ahmed and Sharon Holland immediately come to mind. Moreover, a lot of the women of the generation before me (I’m 40 years old) are still thinking and writing, such as Patricia Hill Collins and Bonnie Thornton Dill. The issue is: how do we get young feminists to turn to the books and to the grassroots, as much as they turn to celebrity feminists and the non-profit industrial complex, for their intellectual and political development? There is nothing more macho than corporate power and empire, feminists ought to be immediately skeptical of both even as we have to engage with them if we live in the United States. I’m worried that not enough self-proclaimed feminists have that skepticism. Black queer studies is probably the most robust area right now, in that it is a field that remains explicitly political and deeply analytical, yet connected to the lives of ordinary people: I’m thinking of scholars like E. Patrick Johnson or Rinaldo Walcott, here. All that to say, I think exposing students to sophisticated ideas and modes of analysis will provide them with the tools to push us further. Young people will be at the vanguard of a revitalized intellectual movement for gender justice.

DM: How do these questions figure into your present and/or future intellectual/political projects?

IP: As I said, I’m writing a book about gender. It is heavily theoretical, rooted in philosophy, jurisprudence and the literature of Black women of the renaissance of the 70s-90s. I’m pushing in a different direction than intersectionality. If we read the Combahee River Collective Statement, we see something that isn’t so specific or sited at the crossroads, but expansive and frankly both Marxist and infused with the sensibilities of liberation movements across the globe. I’m pushing in the direction they, and others, set forth.

DM: And speaking of your work, you’ve mentioned that your recent book, More Beautiful and More Terrible: The Embrace and Transcendence of Racial Inequality in the United States, “called [you], rather than one [you] looked for.” How so?

IP: I think part of being an intellectual is both being an active and constant reader of books and articles and also reading one’s environment. So when I say the book called me, I mean that I didn’t plan to write it but, rather, it took shape through my reading and thinking and living. The same thing with my current book projects. In academia, we are often told to have a fixed research agenda from the beginning of one’s career. I have never subscribed to that approach. I write consistently, but I write where my passion lies, and that is an ever-changing and growing thing. Living as an intellectual is prayerful. You immerse yourself in ideas; you live and love the life of the mind; and at opportune times you find insight thrust upon you. It is a blessing.

DM: Lastly, who would you name as your Black feminist sheroes, those whose lives and work invigorate your own? And why?

IP: This is an extremely hard question. There are so many, so this is just a handful of them: all women I’ve known. Certainly, the women in my family, helmed by my late grandmother Neida Mae Garner Perry, are all models of organic feminism. The sense of personal power that I learned from them has enabled every aspiration. And, as a girl, I met Ella Baker several times. She was elderly by then, and I took her to the park. Knowing who she was, I learned early on that a woman who developed a politic around ways of thinking that are traditionally conceived of as female–collaboration, participation, inclusion, process, humility–could initiate an organization that would change the world. That had a huge impact on me. Mary Helen Washington’s landmark and beautiful, Black Eyed Susans, was the first Black feminist anthology I ever read–I read it when I was in middle school–and she went to my church so doing this kind of work was “real” for me. When I was a young scholar, she praised me for maintaining a class analysis in my scholarship. That attention meant the world to me. Beverly Smith, one of the authors of the Combahee River Collective Statement, and other women of that community were often in my living room for gatherings when I was young, and the conversations they had influenced me. Kate Rushin encouraged me to read Black feminist writers specifically when I was a teenager. I listened. I also began to read her poetry as an adult. It is so human and so Black and so womanly.

IP: This is an extremely hard question. There are so many, so this is just a handful of them: all women I’ve known. Certainly, the women in my family, helmed by my late grandmother Neida Mae Garner Perry, are all models of organic feminism. The sense of personal power that I learned from them has enabled every aspiration. And, as a girl, I met Ella Baker several times. She was elderly by then, and I took her to the park. Knowing who she was, I learned early on that a woman who developed a politic around ways of thinking that are traditionally conceived of as female–collaboration, participation, inclusion, process, humility–could initiate an organization that would change the world. That had a huge impact on me. Mary Helen Washington’s landmark and beautiful, Black Eyed Susans, was the first Black feminist anthology I ever read–I read it when I was in middle school–and she went to my church so doing this kind of work was “real” for me. When I was a young scholar, she praised me for maintaining a class analysis in my scholarship. That attention meant the world to me. Beverly Smith, one of the authors of the Combahee River Collective Statement, and other women of that community were often in my living room for gatherings when I was young, and the conversations they had influenced me. Kate Rushin encouraged me to read Black feminist writers specifically when I was a teenager. I listened. I also began to read her poetry as an adult. It is so human and so Black and so womanly.

In college, I interned at South End Press and, as a result, spent a significant amount of time with bell hooks. Her way of both naming injustice and the thought that produces it, but also remaining hopeful, was inspiring. And she did away with any thought that feminism had to be staid. And then, in my senior year of college, I read Patricia Hill Collins Black Feminist Thought, and I remember calling my mom and saying “THIS is what I want to do when I grow up!” It turns out she knew Pat from Black Catholic activist days. Years later, I got to know Pat myself, and I continue to be amazed by the complex maps she creates of how gender and race and class operate. Lani Guinier inspired me to go to law school and inspires me still with her ability to be critical of the site of her own privilege as a scholar who is at a very powerful institution. I try very hard to replicate that critical posture. My play-sister, Farah Jasmine Griffin, models what it means to prioritize Black women as creative and intellectual subjects, to challenge their place in dominant epistemologies, and open up new epistemological frameworks that center Black women writers and musicians. She teaches us how much we matter. And, Toni Morrison is everything. She announces to the world that the very best, the most profound, the most beautiful and the deepest cutting words emerge from the embodied lives of Black women. What better license to write could there be?

__________________________________

Professor Perry is an interdisciplinary scholar who studies race and African American culture using the tools provided by various disciplines including: law, literary and cultural studies, music, and the social sciences. She has published numerous articles in the areas of law, cultural studies, and African American studies, many of which are available for download at: imaniperry.typepad.com. She also wrote the notes and introduction to the Barnes and Nobles Classics edition of the Narrative of Sojourner Truth. She is the author of Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop (Duke University Press, 2004) and More Beautiful and More Terrible: The Embrace and Transcendence of Racial Inequality in the United States (New York University Press, 2011). Professor Perry teaches interdisciplinary courses that train students to use multiple methodologies to investigate African American experience and culture.

Professor Perry is an interdisciplinary scholar who studies race and African American culture using the tools provided by various disciplines including: law, literary and cultural studies, music, and the social sciences. She has published numerous articles in the areas of law, cultural studies, and African American studies, many of which are available for download at: imaniperry.typepad.com. She also wrote the notes and introduction to the Barnes and Nobles Classics edition of the Narrative of Sojourner Truth. She is the author of Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop (Duke University Press, 2004) and More Beautiful and More Terrible: The Embrace and Transcendence of Racial Inequality in the United States (New York University Press, 2011). Professor Perry teaches interdisciplinary courses that train students to use multiple methodologies to investigate African American experience and culture.

12 Comments