Phantasmagoria; or, The World is a Haunted Plantation

By Selamawit D. Terrefe

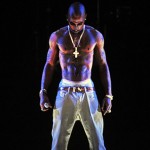

This year’s Coachella Valley Music and Arts Annual Festival debuted a “holographic” performance by the late Tupac Amaru Shakur. Rather than the deployment of a hologram, the technique utilized to deliver the multidimensional representation of Shakur derives from a technology developed shortly after the end of the antebellum era, during the Civil War: “Pepper’s Ghost.” The ironic tropological rupture within the nexus of the term “ghost” with the manipulation of Shakur’s image is made more hauntingly evident if we view Shakur’s “performance” (a catachrestic term upon which I will elaborate below) and structural position in the global sphere as the ghost of slavery: a ghost that permeates structures of violence, fields of visual representation, and our psychic responses to the attendant relations of power that suture blackness to slaveness. Correspondingly, the use of Shakur’s simulacra discloses the exigence of blackness and visual culture, ancillary to what Saidiya Hartman has aptly termed “the afterlife of slavery” (2007).

This year’s Coachella Valley Music and Arts Annual Festival debuted a “holographic” performance by the late Tupac Amaru Shakur. Rather than the deployment of a hologram, the technique utilized to deliver the multidimensional representation of Shakur derives from a technology developed shortly after the end of the antebellum era, during the Civil War: “Pepper’s Ghost.” The ironic tropological rupture within the nexus of the term “ghost” with the manipulation of Shakur’s image is made more hauntingly evident if we view Shakur’s “performance” (a catachrestic term upon which I will elaborate below) and structural position in the global sphere as the ghost of slavery: a ghost that permeates structures of violence, fields of visual representation, and our psychic responses to the attendant relations of power that suture blackness to slaveness. Correspondingly, the use of Shakur’s simulacra discloses the exigence of blackness and visual culture, ancillary to what Saidiya Hartman has aptly termed “the afterlife of slavery” (2007).

Months after the conclusion of Coachella, a NYPD detective shot an unarmed 23-year-old Black woman, Shantel Davis, while she was in the driver’s seat of her car. She is just one among a growing number of Blacks killed this year by police officers and vigilantes. It is also unsurprising that neither Davis’s murder in particular nor (state-sanctioned) violence against Black women in general has garnered as much media attention as the murders of Trayvon Martin, Ramarley Graham, or Alan Blueford (with the exception of many Black independent press sites). However, gender privilege does not apply when engaging in ethical discourses concerning violence against the Black body. For a genocide that continues in perpetuity since the birth of the modern era, privilege is not the purview of those shackled to and tortured by slavery’s aftermath. Hortense Spillers, in her seminal 1987 essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” discloses how the historic conditions of enslavement produced the Black female subject as a being who is “not only the target of rape–in one sense, an interiorized violation of body and mind–but also the topic of specifically externalized acts of torture and prostration that we imagine as the peculiar province of male brutality and torture inflicted by other males.” Equally unsettling is the ease with which pleasure and violence are delinked in conversations concerning the spectacle as well as the quotidian.

Months after the conclusion of Coachella, a NYPD detective shot an unarmed 23-year-old Black woman, Shantel Davis, while she was in the driver’s seat of her car. She is just one among a growing number of Blacks killed this year by police officers and vigilantes. It is also unsurprising that neither Davis’s murder in particular nor (state-sanctioned) violence against Black women in general has garnered as much media attention as the murders of Trayvon Martin, Ramarley Graham, or Alan Blueford (with the exception of many Black independent press sites). However, gender privilege does not apply when engaging in ethical discourses concerning violence against the Black body. For a genocide that continues in perpetuity since the birth of the modern era, privilege is not the purview of those shackled to and tortured by slavery’s aftermath. Hortense Spillers, in her seminal 1987 essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” discloses how the historic conditions of enslavement produced the Black female subject as a being who is “not only the target of rape–in one sense, an interiorized violation of body and mind–but also the topic of specifically externalized acts of torture and prostration that we imagine as the peculiar province of male brutality and torture inflicted by other males.” Equally unsettling is the ease with which pleasure and violence are delinked in conversations concerning the spectacle as well as the quotidian.

What is the relationship between Shakur’s performance and the murder of Shantel Davis? How can we relate the spectacular violence of the state—Shantel Davis bleeding profusely amidst a crowd of onlookers—to modes of representation in pop culture designed for enjoyment and consumption? To begin to answer these questions, I turn to the specific technology utilized in the construction of the illusion of Shakur’s performance. Unlike a hologram that projects a three-dimensional image, “Pepper’s Ghost” is a technique originally deployed to make a two-dimensional image of a ghost appear and disappear. Contemporary examples of this technology appear in Haunted Mansions throughout amusement and theme parks worldwide.  The production company responsible for the projection credits Dr. Dre as the “mastermind” behind the idea for Shakur to perform a set, via this technique, alongside Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg. Notwithstanding, these three Black artists displayed—wittingly or unwittingly—the spectral and corporeal value of Black death to lend the (post)modern world a measure of ontological coherency. As such, it is an image of the effect of Shakur’s murder that mimetically reveals the structures governing the interstitial space between fantasy and violence, identification and performance. The appearance of neither Dr. Dre nor Snoop Dogg’s bodies onstage is less of an apparition than Shakur’s. Indeed, precisely due to the material and psychic value of Black performance-cum-death, the ontological impossibility that signals Blackness (also) sutures Shakur’s image to the equally violent fantasies subtending Davis’s murder. For the erasure of Davis’s slaughter precluded the act: the illegibility of the excessive violence deployed against Davis bears the unethical trace of an antiblack world engendered vis-à-vis positioning Blacks as always-already deserving of torture, violence, and unrecognizable loss– an absence. In so doing, the economic and cultural traffic in abject Black bodies renders American and global forms of entertainment and pleasure as complicit as judicial and extra-judicial modes of execution.

The production company responsible for the projection credits Dr. Dre as the “mastermind” behind the idea for Shakur to perform a set, via this technique, alongside Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg. Notwithstanding, these three Black artists displayed—wittingly or unwittingly—the spectral and corporeal value of Black death to lend the (post)modern world a measure of ontological coherency. As such, it is an image of the effect of Shakur’s murder that mimetically reveals the structures governing the interstitial space between fantasy and violence, identification and performance. The appearance of neither Dr. Dre nor Snoop Dogg’s bodies onstage is less of an apparition than Shakur’s. Indeed, precisely due to the material and psychic value of Black performance-cum-death, the ontological impossibility that signals Blackness (also) sutures Shakur’s image to the equally violent fantasies subtending Davis’s murder. For the erasure of Davis’s slaughter precluded the act: the illegibility of the excessive violence deployed against Davis bears the unethical trace of an antiblack world engendered vis-à-vis positioning Blacks as always-already deserving of torture, violence, and unrecognizable loss– an absence. In so doing, the economic and cultural traffic in abject Black bodies renders American and global forms of entertainment and pleasure as complicit as judicial and extra-judicial modes of execution.

While the foci of violence against Blacks of all presumed genders may appear to have differential modes or loci (according to where they are positioned along a lateral hegemonic axis of white, heteronormative patriarchy), unrestrained violence positions all Blacks, regardless of their various gendered subjectivities, along a vertical axis driven and perpetuated by antiblackness. The system of coordinates circumscribing the paradigmatic, syntagmatic, and interstitial structure are not arbitrary, but rather encompass a specific point of origin in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Slavery not only maintained a system of racial hierarchy regulating how Blacks and non-Blacks negotiated physical space, but also organized the conceptual and psychic spaces determining the classification of the Human and the Black, the living and the dead, individuals who can be victims—whose suffering registers—and objects that have no capacity to suffer. The contemporary landscape of entertainment delineates a specific juncture wherein the socio-political and the psychic reinforce themselves. Just as the incorporation of Blacks within various levels of state institutional apparatuses fails to ameliorate violence in the lives of Blacks, the incorporation of accomplished Black cultural icons and producers fails to negate the purchase of Black abjection. As evidenced by the popularity and work of Oprah Winfrey, Tyler Perry, and Lee Daniels, as well as political, paramilitary, and judicial puppets such as W. Wilson Goode, Leo Brooks, and Clarence Thomas, non-Black, or Human, identification with and desire for antiblack violence haunts the mimetic registers of cultural fantasy.

Scholar and poet David Marriott (2000) states, “A significant subfield of black visual studies is concerned with how visual practices and modes of representation construct and reproduce racial power” (Marriott, 2000). The role of fantasy is critical in both the proliferation of antiblack violence and its elision in ethical meditations on violence writ large, evidenced by not only the fantasy of the Black man as phobic object par excellence, but also the fable regarding Black criminality constructed within juridico-political, social, and psychic spheres. Yet, the spectacular scene of antiblack violence renders it no more ubiquitous than the quotidian, and cis-gendered Black women are subjected to the same conceptualization, treatment, and punishment meted out to Black men: blackness as phobic object, as criminal. The visual practices approximating an archive accounting for the death scenes of Black women labeled as criminal include crime scene photos, mug shots, surveillance videos, and coroner or autopsy reports. Images of Shantel Davis, Rekia Boyd, Shereese Francis, Sharmel Edwards, Alesia Thomas, and Robin Taneisha Williams—all murdered this year—forecast the failure of their suffering to register, to appear.  Although police seized surveillance equipment and video of the Davis shooting from a nearby establishment, a cellular photo image of the Davis crime scene depicts Detective Phil Atkins, the officer responsible for her death, as the focal point of the image.

Although police seized surveillance equipment and video of the Davis shooting from a nearby establishment, a cellular photo image of the Davis crime scene depicts Detective Phil Atkins, the officer responsible for her death, as the focal point of the image.

Abjection, for Blacks, hinges upon the structural and ontological conditions that signal(ed) and exceed its formation. Violence determines not only the specter of the Black body, constantly open to violation, but also its haunting: the negation of an existence prior to its (arrested) arrival. The work of contemporary modes of representation serves to mediate our racial analytics while technological advancements have rendered means to capture, harness, and utilize runaway slaves from beyond the grave. If the crypt comprises a space wherein Black abjection fails to cease, why is remediation, rather than revolution, the focus of dominant discourses concerning antiblack violence? Although the spectral perspectives in this piece regarding images of Black suffering negate the possibility of a differentially gendered antiblack violence, how are our ethical interventions concerning intramural violence clouded by the very fantasies that generate the apparitions of Davis and Shakur? As we begin to answer these questions, the task for Black folks is to question our identifications with racial fantasy and confront our absence, our being as revenants: the phantasmagoria of our evacuated psyches.

Works cited:

Marriott, David. (2000). On Black Men. New York: Columbia University Press.

_____________________________________________________________

Selamawit D. Terrefe is a doctoral student in the department of English at UC Irvine. She also earned an interdisciplinary M.A. from NYU and a B.A. in English from UC Berkeley. Her research bridges grassroots experience as an activist and professional work in the non-profit sector and focuses on the relationship between violence, ontology, and the discourse of radical and revolutionary politics via study in a number of areas: African, African-American, and Black diasporic literature; psychoanalysis; political theory; trauma studies; critical race studies; and Continental philosophy.

Selamawit D. Terrefe is a doctoral student in the department of English at UC Irvine. She also earned an interdisciplinary M.A. from NYU and a B.A. in English from UC Berkeley. Her research bridges grassroots experience as an activist and professional work in the non-profit sector and focuses on the relationship between violence, ontology, and the discourse of radical and revolutionary politics via study in a number of areas: African, African-American, and Black diasporic literature; psychoanalysis; political theory; trauma studies; critical race studies; and Continental philosophy.

8 Comments