“Mixed” Existence: On Rachel Dolezal and Alleles

By Daphne Taylor-García

This article reflects on the colonial/racial divide, Rachel Dolezal’s proclamation, “I don’t give two shits what you guys think…I do consider myself black,” and the questioning, often hesitant identity claims of those thrown into the world as “mixed.”[1]

I spoke a West Indian patois. I don’t recall ever being taunted by anyone in my own neighborhood, but immediately upon leaving, I was challenged by people: “Why are you acting black?” My way of talking and the way I looked struck people outside my neighborhood as an aberration. As a child, I didn’t know enough about the Caribbean and that you didn’t have to appear black to speak in a Trini or Jamaican patois. I was merely talking like my father’s maternal side of the family (that is, black) and like many of the people in my neighborhood. But being accused of pretending to be black raised deep ethical questions for me, even as a youth, for it was at the time hip-hop was becoming popular and white folks were starting to appropriate it. I wanted no part in being seen as participating in this appropriation, and so I started to clip my language and stopped using patois colloquialisms. The accusation, in the context of not knowing more about the Caribbean or how to navigate the nuances between racial identification and racial identity, deeply impacted my life, forcing me to realize at an early age that I could not answer the most fundamental of existential questions: Who am I? Or, more specifically, what am I? I suspect most “mixed” people share stories like this, the culmination of which has deeply shaped our subjectivities and identities in unique and profound ways.

Recently, I read several impassioned articles by “mixed” people responding to the Rachel Dolezal scandal, including “I’m Biracial, And Rachel Dolezal’s Story Is An Outrage To Those Who Struggle With ‘Passing!”; “How Rachel Dolezal Just Made Things Harder for Those of Us that Don’t ‘Look Black’”; and “8 Ways That Rachel Dolezal is Really F***ing Things Up For The Rest Of Us.” The common theme in all of these essays is that Dolezal’s actions have exacerbated the struggle of colonial/racial women who are reduced to their appearance, must deal with the constant erasure of their history, must contend with the negation of their kinship ties and self-knowledge, and are compelled to address confrontational demands to answer the question “WHAT ARE YOU?” in a context where one’s appearance overdetermines one’s existence. In short, they describe the colonial condition. These articles express an anxiety that “mixed” people who can pass might bear the brunt of people’s indignation at Dolezal’s duplicitous opportunism. In Tylea Simone’s humorous words, “Rachel Dolezal just Donnie Brasco’d the fuck out of everyone, and somebody is going to have to pay the price for letting the secret agent in. Unfortunately, I’m pretty sure it’s going to be me.”

One aspect of this complex social issue was highlighted in a story about “mixed” twins that went viral a few weeks ago. One twin appears white, and the other black; both are from the same parents. Alleles can be patterned differently and unpredictably across siblings – even twins, thus making bright-skinned people (gueras) a fact of black, white, and casta communities. Dolezal manipulated this long and fraught history as her entry point to claim authority in black cultural spaces. Poet and playwright Langston Hughes wrote about this theme in his 1925 play, Mulatto.

That Rachel Dolezal was capitalizing on this history of “mixed” people was also (indirectly) brought up by Kai M. Green in his essay, ““Race and gender are not the same!” is not a Good Response to the “Transracial” / Transgender Question OR We Can and Must Do Better.” A subtext of Green’s argument is that the same policing of racial belonging that can be demonstrated towards bright-skinned people (or anyone that is seen as an aberration) is related to the policing of Dolezal’s identity and self-presentation as black, and thus needs to be carefully considered and ultimately rejected if deploying conservative definitions of who “we” are. There seems to be a general understanding across all of these articles that the response to Dolezal’s actions are linked in some way to the lived experiences of “mixed” people. This needs to be examined in our discussions of this new casting of what Green calls “transracial.” I’d like to unpack the visuality operating in Dolezal’s capitalization on “mixed” people’s existence as her segue into black cultural spaces and also tease apart the important differences between people who appear white and those who are white.

The point at which an object appears in our line of sight, we immediately apprehend aspects of the object that determine what it is: A person? A statue? A portrait? It is at this initial point of being seen that Dolezal may appear as a “mixed” person with her curled hair and bronzed skin that was to signify black African ancestry. There are enormous implications for how one looks, as racial profiling makes evident, and Dolezal strategically deployed visual cues to signal a particular positionality. Frantz Fanon pointed out several decades ago that the tendency to reduce black people to their appearance is definitive of the dehumanizing colonial condition. If our critical analyses collapse Dolezal and bright-skinned “mixed” people as the same due to appearance alone, we inadvertently perpetuate a colonial mode of seeing that supplants a people’s complexity with racial stereotypes.

This is a mode of seeing that negates history and kinship ties and thus needs to be dismantled in its entirety. Despite Dolezal’s attempts to reconstruct various aspects of her facticity (her kinship ties, her skin color and hair texture, her childhood experiences), Dolezal did not grow up experiencing the same things as Justine Black, Tylea Simone, or April Siese, that fundamentally shaped their first-person perspective, exemplified in the “us/not us” relations that constitute their subjectivity. And Dolezal certainly never had to contend with growing up as a black woman in Spokane, Washington. These differences do not preclude Dolezal’s assertions, but they do need to be accounted for. The “us/not us” relations I am referring to are multifaceted and will vary across experience, such as the story I opened this article with and the story that Green included in his article. He stated, “Race, and more specifically, blackness, was policed socially and there were moments when some people were made more vulnerable to being ousted than others. I remember the moments when the same students who joined in the chant [JUSTINE AIN’T BLACK!] one day had a sudden change of heart the next. They would fight for and co-sign Justine’s claim on blackness. She could be one of us.’”

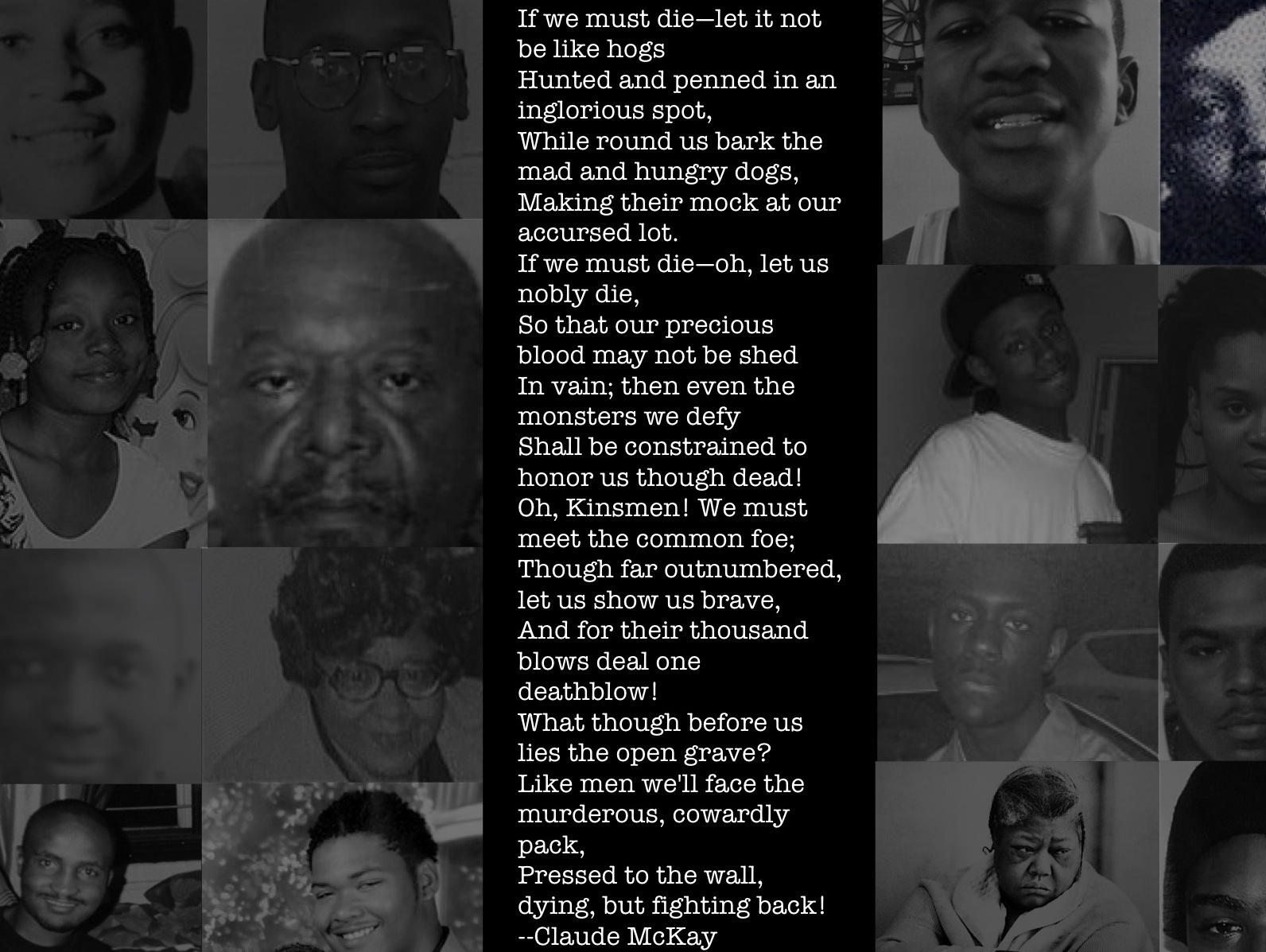

The oscillating, formative experience of being an insider/outsider as a “mixed” person informs one’s answer to the question, “Who or what am I?” that differs in significant ways from Dolezal’s formation. The denigration of the “mixed” individual’s first-person perspective — an aspect of the black perspective, even if a marginal and less radical one — will not be alleviated by affirming the actions of people like Dolezal as “the same” as the life-long experiences and actions of bright-skinned “mixed” people. Rather, their substantive differences require an exposition of how the colonial/racial divide structures selves and society. The work that still remains is to confront the relationship between structure and individual situations that perpetuate making appearance overdetermine existence, undermine kinship ties, erase histories, and ascribe a curious power to the arbitrary patterning of alleles.

Thank you to Veronica Williams, Jennifer Lisa Vest, and Xhercis Mendez for their helpful feedback at different stages of this article and for the insightful conversations we have had on this topic.

[1] The influence of Stoicism on Renaissance and Enlightenment intellectuals gives us the term “mixed” for talking about types of humans and will be explained in my forthcoming book. Although the term is problematic, as Jared Sexton compellingly demonstrates in Amalgamation Schemes, what it continues to signify is important to this article. For more on the colonial/racial divide, gender and sexuality, see Hortense Spillers and Maria Lugones.

_____________________________________________

Daphne Taylor-García is an assistant professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, San Diego where she teaches about the coloniality of gender, sexuality, and being; visuality; existential phenomenology; cultural studies; and decolonial theory and politics. She is writing a book on the long history and politics of “mixed” existence and being in the Americas. Daphne’s father is from Trinidad and her mother is from central Mexico, and she was raised in public housing in Scarborough. She has lived in California for the last 15 years and is currently involved in developing a long-term plan for The Mackey-Cua Project, a multi-generational, queer of color organization in San Diego.

Daphne Taylor-García is an assistant professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, San Diego where she teaches about the coloniality of gender, sexuality, and being; visuality; existential phenomenology; cultural studies; and decolonial theory and politics. She is writing a book on the long history and politics of “mixed” existence and being in the Americas. Daphne’s father is from Trinidad and her mother is from central Mexico, and she was raised in public housing in Scarborough. She has lived in California for the last 15 years and is currently involved in developing a long-term plan for The Mackey-Cua Project, a multi-generational, queer of color organization in San Diego.

0 comments