Ganesh and Kali: Seeing Myself in a Feminist Artist’s Goddess of Destruction

By Chaya Babu

The other day, I furiously penned a blog post after two simultaneous attacks that I am not the right kind of woman.

I had been on the phone with a well-meaning cousin who suggested that my ongoing heartache over the death of my best friend, his little sister, was preventing me from loving in the way I ought to. Read: I should grow up and find a man. He referenced a Facebook post in which I mentioned that my healing process has been slow, fractured, non-linear; that I move forward and back in the supposed stages of grief, and then back again. I am okay with this. Others are not.

On the other line, my mother interrupted with a tirade about my self-presentation, how I look improper and crazy, revealing a deficiency of character or normalcy. My short hair, sometimes pink, purple, or silver, is not what good girls look like. I spark fear in her based on misunderstanding, but by the time it gets to me, it has been translated to repulsion and ire.

I suppose it’s the same with my cousin, and others who tell me, unsolicited and seemingly out of concern, that I should be different.

I felt intensely the truth of my conclusion: that I am supposed to be nothing at all — or at the very least, less of what I am. Even more, though, I felt alone.

When I saw Chitra Ganesh’s Brooklyn Museum exhibit, The Eyes of Time, I had a rush of thoughts about this nothingness, or rather, the opposite: fullness, power, movement, life. Much of Ganesh’s work focuses on depicting the multiplicity of female representation, and South Asian female representation in particular. The Eyes of Time is a lot to take in, and that in itself challenges certain notions of South Asian womanhood — the installation is vibrant, colorful, and multi-dimensional, calling the viewer’s attention to its enormity. The scale of the central figure, a monumental illustration of the goddess Kali with sculptural elements, put me in my place physically. I felt small, of course, in that moment, but I left feeling big.

When I saw Chitra Ganesh’s Brooklyn Museum exhibit, The Eyes of Time, I had a rush of thoughts about this nothingness, or rather, the opposite: fullness, power, movement, life. Much of Ganesh’s work focuses on depicting the multiplicity of female representation, and South Asian female representation in particular. The Eyes of Time is a lot to take in, and that in itself challenges certain notions of South Asian womanhood — the installation is vibrant, colorful, and multi-dimensional, calling the viewer’s attention to its enormity. The scale of the central figure, a monumental illustration of the goddess Kali with sculptural elements, put me in my place physically. I felt small, of course, in that moment, but I left feeling big.

Ganesh’s Kali, the Hindu goddess of destruction and rebirth, is depicted with many limbs, one wielding a bloody sickle; a clock with no hands in place of her face; and long hair flowing away from her body, the black strands spelling out a cryptic message. A skirt of arms hangs from her waist, her torso bare, revealing three breasts. She is fierce, menacing, and yet also serene. She is not pretty.

On either side of her in the massive mural are drawings of two other figures. They appear more realistic in form than the mythological Kali, but have fantastical elements that tie into a theme of time as cyclical, or perhaps non-existent. The woman to her left, warrior-like, is peering through a shard of the galaxy, or a black hole in space, looking into what could be the past or the future; the woman to her right, with antique clock gears where her thoughts would be, seems to have both historical and futuristic elements as well. With the title of the piece, it’s clear that Ganesh is interrogating our framework of time. In much of her work, she uses the disruption of something as unquestioned as chronological order to reject and resist what we accept as absolute.

Kali’s name comes from the Sanskrit word kala, meaning “black” but also meaning “time.” She is associated with the eternal night and darkness, and is the transcendent power of time and change. But her meaning is often misunderstood: many traditional depictions of her show her as naked, savage, and enraged, adorned with a garland of skulls and bearing her blood-red tongue for all to see. Not surprisingly, some believe she is the goddess of death, violence, and sexuality. It’s not that this is wrong necessarily as much as it neglects context.

“The goddess functions on multiple, repeated, changing forms,” Ganesh said, reminding us of the fluid symbolism of mythic narratives and beings. Kali is another form of Durga, the mother of the universe, goddess of creation and preservation, embodiment of Shakti, or divine feminine power. “I thought about this idea that [Kali] is both singular and endlessly divisible at the same, which is something that I really appreciate about playing with feminine representation.”

This ever-shifting nature and plurality of form goes back to the premise of Ganesh’s work, not only at The Brooklyn Museum but as a theme in much of her art. “It’s been complicated because just the fact of my protagonists being brown, that immediately invoked the other kind of interpretive lens — like that was commenting on violence against women in South Asia, when that’s actually not really what I was doing,” she told me. “It’s just that it was kind of time to express alternative articulations of femininity and different kinds of female presences.”

Indeed. It’s strange how we can be who we are, wholly, and yet still be caged in by narrow conceptions of what the world thinks we are or wants us to be based on what it knows. It’s a constant fight. The Kali in The Eyes of Time freed me a little, for a while at least (she also happens to be the goddess of liberation). I’m aware that my statement about how I’m expected to be nothing sounds extreme and hyperbolic. But that’s how it feels in contrast with what I am. As an Indian American woman — and this is likely further delineated by class — the burden I carry to be proper, to be silent, to be small, to be compliant, to be dutiful, to be pure or at least appear that way, to be happy at all times is like a chokehold.

Visibility matters. I am the only person, in the eyes of my family and much of their community, who looks and lives as I do: not always traditionally feminine in my expression and behavior, vocal and active in my radical values, doing what feels right to me on my own timeline. When we see South Asian heroines like Ganesh’s who are curious, wild, poetic, imaginative, mysterious, solitary, imposing, clever, and yes, perhaps even violent or sexual, we have a chance to remember the expansive range of emotions, identities, and iterations that desi women, and all women, can take on and be. We reassert our humanity. All too often, I worry that this is forgotten.

Representation matters. I need more than Mindy Lahiri, who is funny but ditzy, brazen but shallow (which I actually have no major problem with, as I do not expect her to be all things, and hey at least she’s unapologetically sexual), and racist. I need more than Purvi Patel, who was forced into a narrative where she is the victim of her sad conventional Indian upbringing versus of the failing American justice system — she dared to take her body and her fate into her own hands and was punished for it. I need more than Bollywood stars and Miss America, who are sexy but only in comfortable, digestible ways. I certainly recognize the progress in this arena since I was a kid, but there’s still an erasure of women who look, act, and think like me.

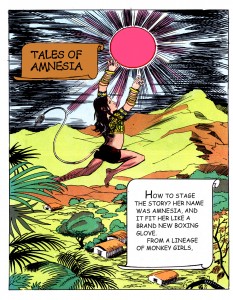

Ganesh pushes to provide more. And not for a political mission, but, as she said, because she creates what she wants to see in the world. Her comics — Tales of Amnesia in particular has many overlapping themes with The Eyes of Time — have badass body-morphing female protagonists with bubbles of dark thoughts and words that nice desi girls should never think or say. She challenges ingrained mythological and literary tropes by giving us multiple feminine forms in one frame and sometimes one being.

Kali, who also appears in Tales of Amnesia, is destruction but also creation. She is death but reincarnation. She is ferocious but also gentle. She destroys in order to put forth new life. Can we not be more than one thing? Can I not feel loss, be angry, and have sexual agency while still being deeply loving, peaceful, and good?

At an artist talk at The Brooklyn Museum, in conversation with curator Saisha Grayson, Ganesh spoke about interpretations of violence in her work, touching upon a sculpture she saw in Mexico City recently of a goddess whose tale originates in being physically ripped apart. But it is this ripping apart from limb to limb, Ganesh explained, that actually created the universe. Across cultures and mythic traditions, ruin and rebirth are inextricably connected.

“Our contemporary culture is saturated with violence and sexuality, but it’s about violence and sexuality being kept in its place,” she said. “So certain kinds of pornographic advertisements are okay but women breastfeeding is not. Violence in war or certain kinds of violence on television are okay, but other iterations of violence are suppressed.”

I cannot help but think of the mainstream media response to the events in Baltimore over the past few weeks. The idea that the city’s history of violence started last month by rioting thugs is conveniently ignorant of the indignity and brutality that laid the groundwork for the eruptions garnering so much attention. Again, representation matters.

When I look to the culture around me to mirror back to me that I am okay, apart from a vibrant but small community of desis like myself because I’m privileged enough to live in a place like New York, I see nothing reflected there. There is dearth, a void, where I know others find themselves easily and often. This lack legitimizes the misunderstandings that allow for assaults on the kind of woman I am and choose to be. Ganesh has drawn me in to the picture. Somehow, in her unlikely protagonists, mostly embodied in vivid brushstrokes and ink and taking on surreal, sometimes not so human forms, I recognize my own humanity — my fullness, power, movement, life.

______________________________

Chaya Babu is a Brooklyn-based journalist and writer. Her work focuses heavily on race and gender with a strong focus on the South Asian American community. She is currently a staff writer at India Abroad and a 2015 Fellow at the Asian American Writers Workshop. Her other work has appeared on Racialicious, The Huffington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Salon, and more. You can follow her @fobbysnob.

Chaya Babu is a Brooklyn-based journalist and writer. Her work focuses heavily on race and gender with a strong focus on the South Asian American community. She is currently a staff writer at India Abroad and a 2015 Fellow at the Asian American Writers Workshop. Her other work has appeared on Racialicious, The Huffington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Salon, and more. You can follow her @fobbysnob.

1 Comment