COLLEGE FEMINISMS: Precious Life

By Sarah de Schweinitz

The first thing I notice in this advertisement is the model’s closed eyes. She appears to be either sleeping or knocked out, looking more like the latter considering how difficult and uncomfortable it would be to sleep on rocks. The model is young, thin, and very pale. Her heavy eye makeup darkens her eyelids with gray, blue, and brown shadows of color. She seems to be alone, and as the accompanying text attempts to explain, she was either “tossed” there or chose to be there. Either way, she appears to be in a depressed state.

This ad promotes self-objectification quite literally, as the model is there solely to be gazed at. Her beauty in this photograph has nothing to do with any form of self-expression, but emphasizes more how she looks with no expression. The model’s body is on display while she is either passed out or so dissatisfied with life that she doesn’t want to move. The title of this photograph, “Gilded Jetsam,” embodies the ideal woman whose gilding doesn’t protect her from being rendered disposable. Usually, something gilded is an object, not a person. Yet, in the photograph the gold’s purpose reduces the woman to an object. The photographer further portrays the woman as jetsam, unwanted goods thrown overboard from a ship and washed ashore. I wonder if the woman in the photograph knew she was being referred to in that way. I wonder if she even saw the title, and if so, how she feels about this.

Marc Jacobs 2014 Ad Campaign. Photo by David Sims/Marc Jacobs

What does this image sell besides the metallic embossed silk dress? I had to look up a couple definitions to understand the photo’s text that reads, “Tempest tossed? Or a case of Royal Ennui?” I was surprised at what I learned. The word “tempest” is a violent, windy storm and the word “ennui” refers to a feeling of listlessness and dissatisfaction arising from a lack of occupation or excitement. Both definitions contextualize the model as extremely disempowered. The ad is selling the idea that being passive (maybe even unconscious) is beautiful and lovely looking.

It is worth pointing out that, under the rules of socially constructed views of gender, that this ad, with this title “Gilded Jetsam,” could only feature a woman. The mainstream concept of female beauty in our society is based on how docile and non-threatening a woman is, and it reaches far beyond the way one physically looks; it substantiates patriarchal oppression. To value these characteristics in someone is to encourage them to remain subdued and even to embrace their own powerlessness.

Cecilia Hartley argues that “Modern American standards require that the ideal feminine body be “small” and that “this model of femininity suggests that real women are thin, nearly invisible” (p. 61). I remember seeing this among my peers in junior high and high school. Adolescent girls would respond to their bodies growing as embarrassing and shameful, particularly if the growing was happening in the “wrong” places such as the thighs, hips, and stomach. I remember stumbling across numerous blogs made by teenage girls that were flooded with images of models promoting “thinspiration.” The idea is always the same: the skinnier, the better. Blogs like these scare me.

Calvin Klein. Photo by SEBASTIAN KIM & FABIEN BARON.

Empowerment and happiness relies on becoming smaller and, therefore, prettier. By the same logic, becoming larger suggests disgust, shame, and fear. These feelings are internalized by seeing “the body [as] suspect, needy, always in danger of erupting into something that will grasp more than is allowed” (Hartley, p. 66). For a boy, growing up is about taking your place in the world. However, a girl’s experience is about not taking up too much space. I believe these internalizations are strongly encouraged and promoted by advertisements in our daily lives.

Advertisements, such “Gilded Jetsam” described above, present women in ways that suggest women are insignificant; they work to make women feel ashamed of their own presence. What better way to manipulate someone’s ideas about their own self-worth than to consistently portray them as helpless. The perpetuation of these negative images of women not only regulates women’s bodies, it also takes a toll on our spiritual and mental well being.

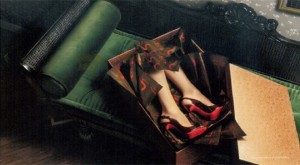

Christian Louboutin. AW14 Lookbook

The increasing context of silent, violent, and oppressive imagery demands our attention.

Christian Louboutin. AW14 Lookbook

Commercial realism, defined by Erving Goffman, is a form of propaganda because it imitates real life so closely that we don’t even realize upon first (or even second, third, etc.) view that it is complete fantasy. It’s what life could be. Romance is presented as two young, thin, often white, and “healthy” heterosexual people embracing one another, engaging in a sexual act, or something as simple as holding hands. The commercial imagery of love is reduced to specific actors of love that leave out the majority of the world’s population. Additionally, the emphasis is placed on the physical act of sex rather than engaging with a variety of ways outside of sex that the erotic enhances life.

Audre Lorde stresses the importance of differentiating between the physical act of sex and the other varied aspects of the erotic and argues that “the function of the erotic is to encourage excellence” (p. 54). If the purpose of the erotic in our lives is to enrich our experiences, then limiting it to superficial bodily acts starts a cruel ripple effect that constrains people. She furthers,

The erotic has often been misnamed by men and used against women. It has been made into the confused, the trivial, the psychotic and plasticized sensation. For this reason, we have turned away from the exploration and consideration of the erotic as a source of power and information, confusing it with the pornographic.

The number one rule in advertising is “sex sells.” If ads are supposed to represent who we are or at least who we want to be, why, then, portray women as subordinate, willfully objectified, and passive? The answer is because it is an effective way of influencing girls and women to not look inside ourselves to our “deepest and nonrational knowledge” (Lorde, p. 53), but to look and focus instead on how we appear on the outside. As Lorde describes, the erotic is a powerful force within us that is systematically suppressed in a society that fears the inner strength women possess.

Alexander Wang. Photo by Steven Klein.

As girls and women, we have been convinced to preoccupy ourselves with our appearance and to mimic models in the countless ads we see each day. Advertising is insidious because it continues to show us as helpless, yet, beautiful and attempts to keep women surrendering their agency so as not to dare encourage us to seek and exercise our real power.

No woman should be made to feel like she is jetsam, and no man should feel as if he is superior to women. As long as the imagery in advertising continues to perpetuate inequity between gender roles, patriarchy firmly remains. However, it is possible to escape from this toxic fog. It begins with resisting the glamorization of the restrictive traditional ideals of femininity and masculinity. It requires us to be aware of the ideas and practice of disparity between men and women. It demands that we explore the full possibilities of the world of the erotic. With awareness comes knowledge, which can lead us beyond the physical and intellectual containments of life.

**********************************************

Sarah de Schweinitz is a freelance author and student. She is currently attending Texas Woman’s University in Denton, TX studying Sociology and Women’s Studies.

Sarah de Schweinitz is a freelance author and student. She is currently attending Texas Woman’s University in Denton, TX studying Sociology and Women’s Studies.

3 Comments