The Color of Infant Mortality

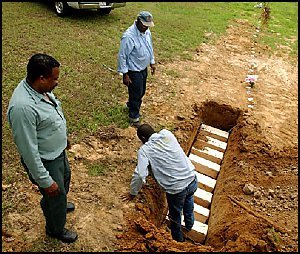

“A pickup truck and a backhoe show up on the days, usually Tuesdays and Thursdays with good weather, when babies are buried at the county cemetery. The first carries the little wooden coffins, and the second digs the hole, maybe three feet wide, where they are placed a foot apart.” – Erin McClam, 2007, writing about Memphis, TN

Babies die. Every day, human beings die in their first year of life. And they perish from a variety of causes: low birth weight, birth anomalies, genetic diseases, “failure to thrive,” inadequate nutrition, abuse, stillbirth, poverty. They die at different ages, some without taking a first breath, others at day one or two or six or 137, and some just shy of their first birthday. These abbreviated lives are daily tragedies, tiny tears in the fabric of human existence and enormous ruptures in families and communities. Each death, singly, is a loss—an occasion for grief and commemoration. Such deaths, like miscarriages, are often publicly invisible, unremarked by anyone beyond grieving mothers, family members, and close friends.

Taken together, however, these deaths are transformed into something else. One solitary infant death is combined with another and then another and so on, until these deaths become a social phenomenon, a collective, a pattern, a vital statistic: Infant Mortality. As a statistic, the infant mortality rate tells us something about a community’s health; it is a kind of bellwether about how cities, counties, states, and nations are faring relative to others. For example, in 2013, the U.S. infant mortality rate was 6.2 deaths per 1,000 births – putting us just between Poland and Serbia and well above the much lower rates of nations such as Japan (2.13), Norway (2.48), and Sweden (2.60). Despite our outrageously expensive health care system, we’re not doing particularly well on the measure of infant mortality vis-à-vis other nations.

Aggregate measures such as the infant mortality rate thus allow us to see things. In parsing the numbers, we notice that poor babies die more frequently; we notice that the United States has more first-day newborn deaths than all other industrial nations combined; we notice that African American babies die at twice the rate of white babies in the U.S.; we notice that babies in some communities, cities, and regions die so frequently that infant mortality is an established fact of life, like racism and police violence; and we notice that in other communities, cities, and regions—those with more racial and class privilege—the death of an infant is shocking because it is so very unexpected. Infant death, normalized in some contexts, elsewhere interrupts the profound structural privilege of believing all will be right in the world.

Infant mortality is about race, poverty, and geography, and the ways that the lives of some women and children in the U.S. are made to matter more—and less—than others. It is also about the multitude of ways that in the United States, we foster life and flourishing for some people while denying others the opportunity to survive, much less to thrive. Echoing philosopher Michel Foucault, we make live and we let die. Infant mortality – and specifically African-American infant mortality, like African-American maternal mortality – is about anti-Black violence and the racialized politics of life and death. To speak of infant mortality in the United States is necessarily to speak of racial inequality and violence—the tragically mundane violence of excess mortality and preventable death.

From Detroit to Milwaukee, Memphis to Washington, D.C., and in many other U.S. cities, we find stark racial disparities in infant and maternal mortality, along with an overall lower life expectancy for African Americans and a variety of other health disparities. We find that despite different histories, political trajectories, and patterns of segregation, in each city African-American babies die at nearly twice the rate of white babies and sometimes at much higher rates depending on specific neighborhoods and zip codes. This spatial distribution of death is not accidental, of course, nor is it simply a function of how and where we measure. There are obvious and longstanding reasons why these babies, and often their mothers, die at such high rates: poverty, lack of access to health care, poor nutrition, racism, and a host of other factors.

In other words, African-American babies and mothers all too often die from structural violence – the entrenched practices and policies that imperil the lives of so many while systematically protecting and nurturing others. And while the infant mortality rate in some locations may be improving, for example through preconception care and other behavior-oriented practices, a racial gap persists. This is because individual solutions – for example, more women taking folic acid or seeking prenatal care – do not necessarily translate into systemic changes. Addressing women’s behavior is ‘easier’ for public health officials and clinicians than, say, fixing entrenched poverty, racism, and violence. Yet poor women, young women, and women of color are most vulnerable to individualized (and coercive) reproductive interventions.

Infant mortality is not only a statistical measure; it is also a reproductive justice issue. Just as women have the right to prevent pregnancies they do not want, they should also have the right to bear and nurture children who will survive and thrive. But unlike the turn of the nineteenth century when a federal effort targeted infant and maternal health, presently very few organizations talk about or work toward reducing infant mortality. Child death is largely not on the radar of mainstream pro-choice organizations, where access to abortion tends to dominate. Nor do anti-choice organizations take up infant mortality despite a pervasive “pro-life” rhetoric. Evidently, “pro-life” does not mean working to reduce structural inequalities, nor does it mean recognizing social contexts in which life is blocked or extinguished. Indeed, for many anti-choice organizations, fetishization of (white) fetal life precludes attention to the survival needs of all pregnant women and their children.

In contrast, SisterSong and other women of color organizations recognize infant mortality as a reproductive justice issue, and they have long done so. Just as they, and we at The Feminist Wire, recognize the murders of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride, and too many other Black children as a reproductive justice issue. Locating African-American infant mortality within broader historical, economic, and social contexts of anti-Black violence—and alongside anti-brown, anti-indigenous violence—draws attention to social structures and practices that chronically disadvantage some while advantaging others, even and perhaps especially at the level of biological life. Infant death is not a result of “cultures of poverty,” wherein blame is lodged with(in) individuals and their so-called pathological behaviors, but rather stems from deep and persistent systems of disregard and disavowal.

And so we must ask: Who do we let live? Who do we allow to die? And who cares?

________________________________________

Monica J. Casper is Professor and Head of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona. A sociologist, her scholarly and teaching interests include gender, race, bodies, reproduction, health, sexuality, disability, and trauma. She’s published several books, including the award-winning The Making of the Unborn Patient: A Social Anatomy of Fetal Surgery, and is currently working on her next book, tentatively titled Abbreviated Lives: Race, Survival, and the Politics of Infant Mortality. She is founding co-editor of the NYU Press book series “Biopolitics: Medicine, Technoscience, and Health in the 21st Century,” as well as managing co-editor of The Feminist Wire and editor/publisher of TRIVIA: Voices of Feminism. More information can be found at www.monicajcasper.com.

Monica J. Casper is Professor and Head of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona. A sociologist, her scholarly and teaching interests include gender, race, bodies, reproduction, health, sexuality, disability, and trauma. She’s published several books, including the award-winning The Making of the Unborn Patient: A Social Anatomy of Fetal Surgery, and is currently working on her next book, tentatively titled Abbreviated Lives: Race, Survival, and the Politics of Infant Mortality. She is founding co-editor of the NYU Press book series “Biopolitics: Medicine, Technoscience, and Health in the 21st Century,” as well as managing co-editor of The Feminist Wire and editor/publisher of TRIVIA: Voices of Feminism. More information can be found at www.monicajcasper.com.

Pingback: Race, Racism and Infant Mortality (Participation) | CES 101 - Fall 2014, Washington State University