Feminists We Love: Katarzyna Marciniak

Dr. Katarzyna Marciniak is Professor of Transnational Studies in the English Department at Ohio University. Her research interests include Transnational Feminist Media Studies, Cinema and Media of Exile and Displacement, Visual Culture, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Migration Studies, Discourses of Nationalism and Globalization, Postsocialist Cultures, and Critical Pedagogy.

Dr. Katarzyna Marciniak is Professor of Transnational Studies in the English Department at Ohio University. Her research interests include Transnational Feminist Media Studies, Cinema and Media of Exile and Displacement, Visual Culture, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Migration Studies, Discourses of Nationalism and Globalization, Postsocialist Cultures, and Critical Pedagogy.

Since graduating from the University of Oregon with a Ph.D. in English with an emphasis in Film Studies, Dr. Marciniak has published widely. Her first book, Alienhood: Citizenship, Exile and the Logic of Difference, was nominated by the University of Minnesota Press for the 2007 Society for Cinema & Media Studies Katherine S. Kovacs Book Award for Outstanding Scholarship in Film and Media. That same year, she co-edited Transnational Feminism in Film and Media with Anikó Imre and Áine O’Healy for the Comparative Feminist Studies Series. She has also been the Series Editor, with Imre and O’Healy, for Global Cinema since 2010, the same year she published Streets of Crocodiles: Photography, Media, and Postsocialist Landscapes in Poland with photography by Kamil Turowski. This year, she co-edited Protesting Citizenship: Migrant Activisms with Imogen Tyler, a reprint of the “Immigrant Protest” special issue of Citizenship Studies published last year. Additionally, SUNY Press will publish Immigrant Protest: Politics, Aesthetics, and Everyday Dissent, also co-edited by Marciniak and Tyler, for the Praxis: Theory in Action Series this November.

Dr. Marciniak has also published extensively in many journals committed to feminist, transnational, and cinema studies, such as Feminist Media Studies, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture, and Camera Obscura: A Journal of Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies, among others. Notably, her article “Pedagogy of Anxiety” (Signs) was the 2010 winner of the Florence Howe Award for outstanding feminist scholarship in the field of foreign languages and literatures by the Women’s Caucus for the Modern Languages.

Her commitment to a pedagogy of excellence is also admirable. At Ohio University, she teaches Contemporary Feminist Theory, Transnational Feminist Practices, Feminist Politics of Bodies, Feminist Film: Aesthetics and Politics, Immigration, Race, Nation, Genders, Sexualities, and Visual Analysis, and many other courses committed to the study of gender and feminism. For these reasons, she holds the honor of Presidential Teacher from 2013-2016, an award that is based on “excellence in teaching and meritorious academic pursuits both inside and outside the classroom, as acknowledged by peers and students.” She has also won the Jeanette G. Grasselli Brown Faculty Teaching Award from the College of Arts & Sciences, the Transformative Faculty Award from the Office of the Provost, and the Arts and Sciences Dean’s Outstanding Teacher Award.

********************

HRL: You’ve been thoroughly engaged in transnational studies for more than 15 years. What inspired you to pursue this area of study?

HRL: You’ve been thoroughly engaged in transnational studies for more than 15 years. What inspired you to pursue this area of study?

KM: When I started my work, the field that we now call transnational studies barely existed. I had no idea where I should send my work for publication. Nowadays, there are journals like Transnational Cinemas or Journal of Transnational American Studies. There was the field of immigration studies but it always felt like a marginal space to me, an area of ‘special interests.’ My dissertation title was “Quivering Ontologies: Exiled Bodies and Transnational Narratives.” There is a funny story about this title. When I received a contract from the University of Minnesota Press for my first book, the editor called me and said, “We are all very excited about your book but, just so you know, we all agreed that you cannot possibly keep ‘quivering ontologies’ in the title. It would be catastrophic for marketing purposes!” So we settled on “Alienhood.” I, of course, don’t regret that change but I always thought that my life and my work are intimately connected to the idea of quivering ontologies – the kinds of bodies that do not quite belong to a particular nation, or belong to one uneasily or provisionally, bodies that are somewhat liminal and therefore questionable. I think immigration is all about such quivering. Also, foreignness as a concept and as a lived experience is something that preoccupies me along with issues of legality and illegality. One can be a palatable foreigner (grateful, domesticated one, with a ‘cute’ accent), or a dangerous foreigner (a thief of ‘our’ national goods or, worse, a terrorist); foreignness is always overdetermined.

HRL: In your estimation, what are some of the most prolific and exciting theories and critical practices that have been developed in transnational studies? Additionally, in what ways do you think the field can be further developed?

KM: In my work with Anikó Imre and Áine O’Healy, in particular, I have been exploring issues of feminist incommensurabilities vis-à-vis the concept of difference and sameness. We all know that in the United States, the field of Women’s and Gender Studies, or Feminist Studies, has moved through a multiplicity of phases that have by now enabled feminist work to move beyond Western-centric, U.S.-centric, First/Third World binary approaches and beyond the already superseded discourses of “global sisterhood.” Both difference and incommensurability are obviously not new concepts in feminist studies, but the critical examination of these concepts in the context of transnationality is an exciting and important turn. We started our work at a time when the transnational designator was emerging with increasing vigor (through the groundbreaking work of Gayatri Spivak, Chandra Mohanty, Ella Shohat, Jacqui Alexander, Inderpal Grewal and Caren Kaplan), and yet the space of Eastern Europe, often referred to as the Second World, seemed like a territory of perpetual invisibility even for these scholars. Feminist voices from socialist and now postsocialist spaces really had no presence at that point in feminist scholarship in the United States. The emergence of postsocialist feminist studies is definitely continuing to orient transnational feminist scholarship in a more inclusive direction. Discourses of incommensurability are often critical in transnational feminist encounters of this sort; for example, the metaphor of waves used to describe the successive phases of feminism, which is historically valid in the United States, has been nonexistent in the Eastern European regions.

As for the new developments, several are already emerging; ideas of precarity, affect, sexualities vis-à-vis asylum-seeking and refugeeism, as well as discourses of disabilities are new critical dimensions that continue to infuse the transnational with crucial relevance to our time. Last April at Ohio State University, I participated in the Global Human Rights, Sexualities, and Vulnerabilities Symposium. Wendy Hesford and Rachel Lewis are co-editing a special issue of Sexualities that will feature some of the work presented there that deals precisely with those kinds of intersections.

HRL: It’s hard to believe that we met over a decade ago when I was a graduate student in the English Department at Ohio University. Still, your influence on me has not waned over the years. I don’t know if I ever told you this, but I heavily modeled my course on Transnational Feminisms after your Transnational Feminist Practices course. Like you, I teach Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, Claire Denis’ Chocolat, and Trinh T. Minh-Ha’s Surname Viet Given Name Nam. What are you up to these days in that course? Are there any other films you might suggest?

HRL: It’s hard to believe that we met over a decade ago when I was a graduate student in the English Department at Ohio University. Still, your influence on me has not waned over the years. I don’t know if I ever told you this, but I heavily modeled my course on Transnational Feminisms after your Transnational Feminist Practices course. Like you, I teach Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, Claire Denis’ Chocolat, and Trinh T. Minh-Ha’s Surname Viet Given Name Nam. What are you up to these days in that course? Are there any other films you might suggest?

KM: Heidi, I am so moved to hear that you modeled your course on the graduate seminar we both experienced so many years ago. I was a junior scholar then, having been a doctoral student until just a short time before we met; my first book, Alienhood, was not out yet. I had truly inspirational teachers at the University of Oregon where I did my Ph.D. My main advisor, Linda Kintz, a scholar who specialized in feminist theory and critical theory more generally, was someone whose teaching I observed with awe. I had no idea that, in many ways, I would be emulating her performance years later, when I became a faculty member myself. I guess she ‘got to me’ through intellectual osmosis, infusing me with her exemplary theoretical rigor and care; this is still very much a part of me. And then, of course, I was also under a strong influence of my film mentors, Julia Lesage and Kathleen Rowe Karlyn, both fantastic scholars and teachers who gave me foundational knowledge in film history and film theory and opened the doors to my current work in film and media studies. I still remember my first class session with Julia Lesage where she asked us to talk about our media habits as a way of introducing ourselves to each other. She then proceeded to reveal that she was an avid watcher of The 700 Club! I remember walking out of class with another graduate student and telling him that I clearly needed to drop the class! He grabbed my arm and said, “You have no idea who she is, do you?” Of course, on that day, as a fresh graduate student, I had no clue that I would have the privilege of studying with a scholar who belonged to the first cohort of feminist film theorists in North America! So I am particularly grateful for your acknowledgment that my graduate seminar influenced you in such positive ways. This is testimony to a certain feminist pedagogical afterlife that some of us have a good fortune to profit from.

I am still teaching this course and it has moved through multiple permutations. I am using some newer films, such as Courtney Hunt’s Frozen River (2008), Cherien Dabis’ Amreeka (2009), Nancy Savoca’s Dirt (2003), or Anayansi Prado’s documentaries, Maid in America (2004) and Children in No Man’s Land (2008). Through my recent work, I have become invested in the exploration of border politics, foreignness and liminality, immigration, and transnational encounters. Since 2000, there has been a rich proliferation of transnational cinema in various global contexts, and I am also interested in films created by male directors. In 2011-2012, I was a Visiting Scholar in Transnational Media and Race Studies at Occidental College in Los Angeles, where I spent a year primarily teaching transnational cinema. My experience at Occidental was exceptionally productive, as it provided me with the opportunity to develop courses in this area and to enhance my research interests. I taught some amazing films, such as Eran Riklis’s The Syrian Bride (2004), Julian Schabel’s Before Night Falls (2000), or Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Biutiful (2010).

HRL: Speaking of transnational feminist films, you co-edited Transnational Feminism in Film and Media with Anikó Imre and Áine O’Healy about 7 years ago. In the “Introduction,” you argue, “The ‘foreign’ has been the key operative term of the Bush administration, employed almost exclusively to demonize, and thereby to provoke defensive patriotism. The growing anti-immigrant sentiments in the United States in the post–9/11 era ever more vigilantly target ‘aliens,’ specifically nonwhite aliens, as a source of national worry […] The post–9/11 anxiety, and the subsequent ‘war on terror,’ have amplified a desire of global proportions to police and discipline those who are classified as questionable others.” What are your thoughts about the Obama administration’s relationship to foreignness over the past 1 ½ terms? Do you see this manifesting in contemporary film about the “other?”

HRL: Speaking of transnational feminist films, you co-edited Transnational Feminism in Film and Media with Anikó Imre and Áine O’Healy about 7 years ago. In the “Introduction,” you argue, “The ‘foreign’ has been the key operative term of the Bush administration, employed almost exclusively to demonize, and thereby to provoke defensive patriotism. The growing anti-immigrant sentiments in the United States in the post–9/11 era ever more vigilantly target ‘aliens,’ specifically nonwhite aliens, as a source of national worry […] The post–9/11 anxiety, and the subsequent ‘war on terror,’ have amplified a desire of global proportions to police and discipline those who are classified as questionable others.” What are your thoughts about the Obama administration’s relationship to foreignness over the past 1 ½ terms? Do you see this manifesting in contemporary film about the “other?”

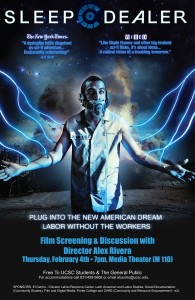

KM: Actually, these kinds of questions are taken up in Immigrant Protest in a chapter where I interview an American filmmaker Alex Rivera. Rivera directed Sleep Dealer (2008), a film referred to as the first “Third World science-fiction” and a “cyberpunk of the south.” Sleep Dealer, like Rivera’s other films, engages the politics of the Mexico-U.S. border and highlights the intersecting themes of migration, labor, and technology. It is a stylistically innovative narrative that plays with a notion of “tele-migration” or a “long-distance work.” The protagonist is a “nodal worker,” that is, someone who is working in the United States while his body physically remains in a factory in Tijuana. These factories are called “sleep dealers” because if one works long enough, one collapses. When the protagonist gets the desired nodes, his own cybernetic implants, and plugs in for the first time, he reflects: “Finally, I could connect my nervous system to the other system – the global economy.” The voice of the node factory operator, with a good dose of sarcasm, sums up most desirable policy on immigration for the U.S.: “This is the American Dream. We give the Americans what they have always wanted – all the work and none of the workers.”

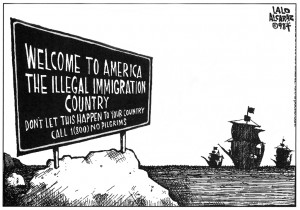

In the interview, Rivera speaks about various historical conflicted and contradictory developments that have affected the ways in which the nation experiences and imagines the “immigration problem”: the creation of NAFTA (the promise of free trade and borderless economy) and this assumed borderlessness that is crystalized in the phrase “the global village” and embodied by the Internet vis-à-vis the acute militarization of borders and simultaneous criminalization of working people. So, as he says, throughout various administrations, we have witnessed a particular investment in the process of “securing the nation” – be it through Operation Gatekeeper started under the Clinton administration, or through the Secure Communities national program began under the Bush administration and strengthened under the Obama administration. This program is connected to a new, controversial legislation in Alabama and Arizona, one that created multiple ostracizing stipulations, including requiring immigrants to carry their documents at all times – which makes Latina/os especially (documented or not) vulnerable to surveillance and identity checks. Nicholas De Genova, who writes extensively on these issues, coined the phrase, the “spectacle of security.” It is clear that this spectacle is not tied to a particular administration but, rather, it supports “Fortress America” in an ongoing way – a historical construct emphatically reasserted in the post 9/11 era alongside the xenophobic rhetoric of “immigration reform” and the abjectification of undocumented workers. In the end, I think Rivera’s film offers a powerful point: the nation profits from the work but doesn’t want the bodies that do this work.

HRL: I was so excited to learn that SUNY Press will publish Immigrant Protest: Politics, Aesthetics, and Everyday Dissent this November, a book you co-edited with Imogen Tyler. You recently told me that you contributed an essay to the book entitled “Pedagogy of Rage.” You were right that I’d be very intrigued by this. So, I’m hoping that you can tell us a little bit about the book and this essay.

HRL: I was so excited to learn that SUNY Press will publish Immigrant Protest: Politics, Aesthetics, and Everyday Dissent this November, a book you co-edited with Imogen Tyler. You recently told me that you contributed an essay to the book entitled “Pedagogy of Rage.” You were right that I’d be very intrigued by this. So, I’m hoping that you can tell us a little bit about the book and this essay.

KM: First, let me tell you about Imogen Tyler for whose work I have the highest admiration. She has been my inspiration for a long time. She is a well-known feminist scholar who is so brilliant yet conducts herself with amazing humility. As we were working on the book for many years, she would often say, “You and I, we keep our heads down and work.” I know that such collaborations don’t happen very often; we knew how to ethically divide our work. And the process of putting together this book was quite complex, as we had contributors working in both the United States and Europe, not only representing a broad variety of interests but also coming from different cultural backgrounds (Bosnia, Croatia, Germany, Greece, Romania, UK). They contributed work on Islamophobia, Latino border politics, Eastern European discourses of whiteness and performances of foreignness, Israeli/Palestine border zone, asylum seeking in the UK, transnational feminist activism, and an exploration of citizenship through arts practice. The project is a hybridized, interdisciplinary collection, featuring scholars working in the humanities and social sciences, as well as artists and activists engaged in immigrant protest. In the end, Imogen and I argue for a noborder politics and we claim that such a politics can only be enacted through a “noborder scholarship.”

Imogen and I met during the work on Transnational Feminism in Film and Media; she was one of our contributors. We then started reading each other’s work and we both felt an undeniable intellectual pull, realizing that we had a mutual interest in protest, rage, and immigration politics. When we sent our call for the “Immigrant Protest” contributions, we got more responses and abstracts than we might have imagined. At that point, we both thought we would co-edit a special issue of a journal on the topic. But the number of potential contributors was so high that it became obvious to us that we needed to start two projects. One is a special issue of Citizenship Studies, published in April 2013, under the title of “Immigrant Protest”; the other is our forthcoming book.

As for my contribution to the book, “Pedagogy of Rage”: for a long time, I have been exploring the affective and conceptual underpinnings of “immigrant rage.” I am fascinated by the concept of rage and, of course, I have been influenced by the writings of bell hooks, Jack Halberstam, and Audre Lorde on the subject. So, while there is a definite feminist discourse on rage, the idea of immigrant rage, I have realized, is one that still needs to be articulated. If feminist rage is something feared and often mocked (in order to belittle its power), then feminist immigrant rage is definitely a hard-core offense. We know that an immigrant is expected to be quiet and grateful; barely visible and barely audible, but at the same time a hard-working body that pays off her debt to the host nation. In 2006, I published a piece on immigrant rage in differences. Last year, I published “Legal/Illegal: Protesting Citizenship in Fortress America” in Citizenship Studies. I also started writing about pedagogy in conjunction with the transnational and feminist politics and published “Pedagogy of Anxiety” in Signs. When the time came to write my contribution to Immigrant Protest, I knew I wanted to explore the idea of “pedagogy of rage.”

As for my contribution to the book, “Pedagogy of Rage”: for a long time, I have been exploring the affective and conceptual underpinnings of “immigrant rage.” I am fascinated by the concept of rage and, of course, I have been influenced by the writings of bell hooks, Jack Halberstam, and Audre Lorde on the subject. So, while there is a definite feminist discourse on rage, the idea of immigrant rage, I have realized, is one that still needs to be articulated. If feminist rage is something feared and often mocked (in order to belittle its power), then feminist immigrant rage is definitely a hard-core offense. We know that an immigrant is expected to be quiet and grateful; barely visible and barely audible, but at the same time a hard-working body that pays off her debt to the host nation. In 2006, I published a piece on immigrant rage in differences. Last year, I published “Legal/Illegal: Protesting Citizenship in Fortress America” in Citizenship Studies. I also started writing about pedagogy in conjunction with the transnational and feminist politics and published “Pedagogy of Anxiety” in Signs. When the time came to write my contribution to Immigrant Protest, I knew I wanted to explore the idea of “pedagogy of rage.”

If you think about rage in our culture, there are definitely conflicting discourses surrounding this concept, a certain kind of schizophrenia, especially in media culture. If you watch Dr. Phil, for example, you learn that rage is unhealthy and needs to be cured and suppressed. But we also know that the contemporary social and cultural landscape is not free of multiple, deliberate manifestations of rage. It is enough to consider The Jerry Springer Show as just one indicative example of this. This is a show that thrives on eliciting rage from both invited guests and audiences. In fact, it actively encourages foul language and screaming, and orchestrates on-stage verbal attacks, physical aggression, and the intervention of security guards. It is crucial, of course, to remember that the guests on this show and others like it are often people of color, or whites coming from deprivileged social strata. Many are severely overweight, many are working class, and many are single parents, collectively creating the impression that “regular” folks do not do rage, just the “unfortunate” ones. Then, there is, of course, both online and offline anti-immigrant rage that is often presented as righteous and necessary for the protection of the “purity” of the nation. This form of rage is mainly enacted by white males who assume the position of “defenders” of the nation. So this is an almost sanctioned rage.

“Pedagogy of Rage” articulates this complex context and links it to pedagogical practices. I write about my students’ affective responses while studying Courtney Hunt’s 2008 border film, Frozen River, and reflect on the possibilities and limits of enacting “immigrant protest” and “immigrant rage” in the classroom. My interest lies in rage as a political category of intervention, one that can influence students’ sensibilities and open them up to new ways of thinking about resistance to oppressive forms of phobic nationalisms and exclusionary practices of citizenship.

HRL: You’re currently the Palgrave MacMillan Series Editor for Global Cinema, also with Anikó Imre and Áine O’Healy, which “publishes innovative scholarship on the transnational themes, industries, economies, and aesthetic elements that increasingly connect cinemas around the world” and “promotes theoretically transformative and politically challenging projects that rethink film studies from cross-cultural, comparative perspectives, bringing into focus forms of cinematic production that resist nationalist or hegemonic frameworks.” The series includes Prismatic Media, Transnational Circuits: Feminism in a Globalized Present by Krista Geneviève Lynes, Transnational Stardom: International Celebrity in Film and Popular Culture edited by Russell Meeuf and Raphael Raphael, and Silencing Cinema: Film Censorship around the World edited by Daniel Biltereyst and Roel Vande Winkel, among others. Can you discuss what we can expect from the series in the coming months/years?

HRL: You’re currently the Palgrave MacMillan Series Editor for Global Cinema, also with Anikó Imre and Áine O’Healy, which “publishes innovative scholarship on the transnational themes, industries, economies, and aesthetic elements that increasingly connect cinemas around the world” and “promotes theoretically transformative and politically challenging projects that rethink film studies from cross-cultural, comparative perspectives, bringing into focus forms of cinematic production that resist nationalist or hegemonic frameworks.” The series includes Prismatic Media, Transnational Circuits: Feminism in a Globalized Present by Krista Geneviève Lynes, Transnational Stardom: International Celebrity in Film and Popular Culture edited by Russell Meeuf and Raphael Raphael, and Silencing Cinema: Film Censorship around the World edited by Daniel Biltereyst and Roel Vande Winkel, among others. Can you discuss what we can expect from the series in the coming months/years?

KM: Since the inception of this initiative, we have shepherded six books through to print. All were published in 2013. Even though the series does not have a distinctly feminist focus, we are particularly on the lookout for manuscripts invested in feminist politics and aesthetics; in fact, the inaugural volume published in the series was the book by Krista Geneviève Lynes. The next book, due for publication in May 2014, is New Documentaries in Latin America, edited by Vinicius Navarro and Juan Carlos. We also have several projects in the making: one on prostitution, one on global cinema and girlhood, and one on cosmopolitan film cultures. The series is a very exciting venture for us, as it allows us to connect with scholars all over the globe and to promote projects that inspect global film cultures in theoretically astute ways.

HRL: I’ve always been enamored by formidable collaborators in scholarship, especially in transnational studies, like Inderpal Grewal and Caren Kaplan, Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, and Chandra Talpade Mohanty and M. Jacqui Alexander. It seems that you might be building such a relationship with Anikó Imre and Áine O’Healy. As a growing and developing scholar, I’m hoping you can discuss how such collaborations become possible. In other words, how does one cultivate these kinds of relationships?

KM: Áine O’Healy, Anikó Imre, and I met around 2005 through conferences and publications. It has been a galvanizing experience to work with both of them and we have, indeed, become an informal editorial collective. The three of us are passionately interested in cinema and feminist politics and invested in transcultural collaborations – feminist work across borders. Borders have been definitely an intimate part of our lives: we all work in the United States but come from different ‘elsewheres.’ Áine comes from Ireland, Anikó grew up in Hungary, I grew up in Poland. Both Anikó and I spent our formative years behind the Wall and experienced different versions of Soviet-imposed socialism. Anikó calls us ‘postsocialist diasporics.’ Obviously the experiences of immigration and being ‘foreign’ and ‘transnational’ in the U.S. academia are connecting factors among us yet it is our differences that inspire us more than certain similarities that we also share.

In 2007 we published Transnational Feminism in Film and Media in the Comparative Feminist Studies Series under the Series Editorship of Chandra Talpade Mohanty. Since its publication, the TFM project has become recognized as a groundbreaking intervention, linking discourses in transnational feminisms with transnational cinema and media, and signaling the emergence of a new area of scholarship—transnational feminist media studies—a field that has been growing in momentum ever since. Having realized, with much excitement, that our work was tapping into new and important areas of feminist inquiry, our next project was a 2009 co-edited special issue of Feminist Media Studies with the topic “Transcultural Mediations and Transnational Politics of Difference.” In the course of completing these projects, we had the invigorating opportunity to collaborate with feminist scholars with ties to Britain, Germany, Hungary, India, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Romania, Switzerland, and Turkey.

Our work as academics is often very solitary so when you find the right scholars to collaborate with, you deeply appreciate what such a work can accomplish and you cherish affinities that are born in the process of feminist encounters. If we hadn’t done these collaborative projects, I know I would be less of the person and the scholar that I feel I am now. Such collaborations ask you to step outside of your own skin, take risks, and embrace new and exciting ways of thinking. I am very grateful for this work.

HRL: I’d like to end by asking about your future projects. Rumor has it that you’re working on a manuscript tentatively entitled Cinema and Pedagogy: Transnational Encounters in the Classroom. Can you tell us a bit about that project and when we might expect to find it on the shelves?

HRL: I’d like to end by asking about your future projects. Rumor has it that you’re working on a manuscript tentatively entitled Cinema and Pedagogy: Transnational Encounters in the Classroom. Can you tell us a bit about that project and when we might expect to find it on the shelves?

KM: Yes, as I have mentioned, I have been developing an interest in pedagogy and its ethical dimensions. Many of us teach transnational cinema yet barely speak about our pedagogical practices beyond casual conversations with peers or institutional assessment exercises. And for many of us, feminist oppositional practices clearly happen in the classroom, “on the ground,” through various pedagogical models we try out and experiment with. My next project is about teaching transnational cinema and the various ethical contingencies that arise when we grapple with foreignness, migration, liminalities, and border-zones in the classroom. I have been thinking about these various cinematic terms connected to spectatorship such as identification, disidentification, suture, and empathy, and over the years I have observed what happens in my classroom when we engage with transnational texts. But this project has to wait a bit since I am now involved in a sister-project titled “Teaching Transnational Cinema: Politics and Pedagogy” with my UK collaborator, Bruce Bennett. This collection of essays is already underway and we have an amazing international group of contributors. If we are successful in our timing, it will be published next year.

0 comments