On Faith and Feminism: A “Sermon”

By Mary Kathryn Dean

The Texts:

When a great crowd gathered and people from town after town came to him, he said in a parable: ‘A sower went out to sow his seed; and as he sowed, some fell on the path and was trampled on, and the birds of the air ate it up. Some fell on the rock; and as it grew up, it withered for lack of moisture. Some fell among thorns, and the thorns grew with it and choked it. Some fell into good soil, and when it grew, it produced a hundredfold.’ As he said this, he called out, ‘Let anyone with ears to hear listen!’

Then his disciples asked him what this parable meant. He said, ‘To you it has been given to know the secrets* of the kingdom of God; but to others I speak* in parables, so that “looking they may not perceive, and listening they may not understand.” ‘Now the parable is this: The seed is the word of God. The ones on the path are those who have heard; then the devil comes and takes away the word from their hearts, so that they may not believe and be saved.The ones on the rock are those who, when they hear the word, receive it with joy. But these have no root; they believe only for a while and in a time of testing fall away. As for what fell among the thorns, these are the ones who hear; but as they go on their way, they are choked by the cares and riches and pleasures of life, and their fruit does not mature.But as for that in the good soil, these are the ones who, when they hear the word, hold it fast in an honest and good heart, and bear fruit with patient endurance.

He said therefore, ‘What is the kingdom of God like? And to what should I compare it? It is like a mustard seed that someone took and sowed in the garden; it grew and became a tree, and the birds of the air made nests in its branches.’

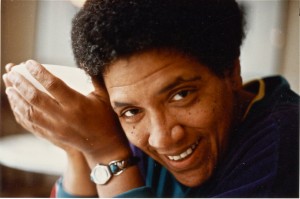

Audre Lorde: Transformation of Silence into Language and Action

In becoming forcibly and essentially aware of my mortality, and of what I wished and wanted for my life, however short it might be, priorities and omissions became strongly etched in a merciless light, and what I most regretted were my silences. Of what had I ever been afraid? To question or to speak as I believed could have meant pain, or death. But we all hurt in so many different ways, all the time, and pain will either change or end. Death, on the other hand, is the final silence. And that might be coming quickly now, without regard for whether I had ever spoken what needed to be said, or had only betrayed myself into small silences, while I planned someday to speak, or waited for someone else’s words.

I was going to die, if not sooner then later, whether or not I had ever spoken myself. My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you.[i]

***

I would like to place this Christian scripture and this Lordean text in conversation with each other. Audre Lorde’s challenge to break silences is powerful, and is, as she acknowledges, difficult to fulfill. I am a queer Christian writer student feminist, and I am neither alone nor wrong in my politics or theology. Too often I keep silent about some fraction of that: I know not to out my queer self in some Christian circles, and I certainly know to avoid talking about church or God in most queer or feminist circles. There is some perceived safety in staying silent: maybe if I don’t tell who I am, maybe if I let the person continue to bully me, or my friend, then I will live to speak another day. We all feel this acutely, that, potentially, silence will buy us time to speak. But it does not. We are not meant to survive regardless, says Lorde, so we should use each day we have to speak as loudly as we can. We must first acknowledge that we seek shelter in silence, and then we must break that silence – shatter it into pieces if we are ever to spread the Kingdom of God onto good soil so that it can blossom for others to share in its glory.

From an impossibly tiny seed comes this gorgeous field, of bright yellow flowers, of trees that grow quickly and provide homes for many kinds of wildlife.

Did you know that mustard is an invasive species? But it is beautiful, and it has some good to it too, as long as it has soil that is healthy for it to flourish in. The miniscule seeds that grow into such flavorful seasoning have such great potential if given the right environment, and so do we, and so does the Word of God.

In the spirit of breaking silences, and of spreading the Word of God like wildflowers through a new country into rich soil, I would like to share my story, with the hope that you will take it and use it. I am a queer Christian feminist writer and student. As Audre Lorde says so concisely, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

I often experience spaces where I feel it would be safer for me not to come out – not to share my story or not to share one of the aspects of it. I do not always mention that I am a writer, even though I have been writing as long as I could string words together into sentences. I do not always mention that I am on food stamps, rather I focus on my prior elitist experiences at Bryn Mawr College. But I have learned that my silence will not protect me. I cannot be just a feminist, without its being informed by my race or my religion or my education or my sexuality; I cannot be queer without an understanding of how it fits into and is defined by my theology or my socioeconomic class. I do not and can not lead a single-issue life. I must speak, loudly, about all the parts of me and how they fit together, so that you might not expect just one thing from me or other people in some way like me.

So this is me, speaking loudly. Lorde challenges us all to step outside of our comfort zones, to defeat the machinery that will kill us one way or another:

That visibility which makes us most vulnerable is that which also is the source of our greatest strength. Because the machine will try to grind you into dust anyway, whether or not we speak.

To this end, stepping outside of my comfort zone and conquering the silences which endlessly attack me and try to envelop me, I will attempt to reassure another generation of queer Christians who are fighting hegemony, seeking ordination, blessing marriage ceremonies, defeating the patriarchy. In breaking my own silence here, I am also encouraging many feminists to step out of their comfort zones and to understand that religious faith, particularly Christian faith but also religion more broadly, is not necessarily in opposition to feminism and social activism.

I grew up in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and it was here that I first developed a real sense of faith. When I was thirteen, I stumbled into some conservative theology and considered myself a conservative Christian. I vaguely remember my grandmother and my parents trying to dissuade me from what I was reading, but I might be misremembering because now they are far more conservative than I am.

I moved in with my Orthodox Presbyterian great-grandmother the summer after I came out, at 19 years old. Her church actively preached against homosexuality, evangelizing their word through contemporary music on the Wildwood, NJ, boardwalk on summer evenings. After I dropped her off at chapel, I would walk the boards and try to figure out why on Earth God had put these two events so close to each other in my life. I convinced myself that, while God had been, and was, important to me, I could not be a “Christian” if these were his followers. I felt abandoned – like God had stopped listening to me even before I stopped talking to Him. I remember crying often during my sophomore year of college – My God, My God, why have you forsaken me? For two years I struggled with my relationship with God and with the Church.

Eventually I was able to talk to my parents’ pastor. Eventually I found That All May Freely Serve, a group of Presbyterians fighting for ordination equality, and eventually I grew familiar with More Light Presbyterians, a network of Presbyterian Churches that are inclusive to lesbians, gay men, bisexual people, and transgender people. Eventually when I moved out on my own, I found my own congregation that considers itself LGBT-friendly. Eventually I heard the good news, that I was not alone. It is through these affirming pastors, PC(USA)-affiliated groups, and welcoming congregations that I discerned my own call to ministry in the Presbyterian Church. I am in the process of being taken under care by the Session, and, God willing, I will attend seminary after I graduate from Temple University. With that, I intend to spread the good news like wild mustard – that young, queer teenagers of faith are not alone.

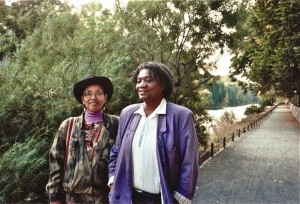

I was so blessed as to meet Dr. Elizabeth Lorde-Rollins and Professor Melinda Goodman in Professor Aishah Shahidah Simmons’ graduate and undergraduate seminar at Temple University dedicated to studying the life, works, and legacy of Audre Lorde. They both spoke to Audre Lorde’s spirituality: her having been raised Catholic, her cultural superstitions, her understanding that “the love of women healed [her]”post- mastectomy, and her belief in heaven. In The Cancer Journals, Lorde speaks out against “superficial spirituality,” but loudly in favor of support networks, which strengthen one’s spirit. While I have not had cancer, I do have an autoimmune disease which once required (and probably will require again) a surgery to address. When I was in the hospital for several days, it was the support of my faith networks across the country – my churches in Philadelphia and Frederick, MD, my mentor in California (who, in fact, took the picture of the rampant mustard I shared earlier), and my team members from General Assembly – who helped me heal more wholly by praying for me, by visiting me, by sending me flowers and encouraging me. Each of the people who cared for me in my illness was aware that I am both queer, and that I am a woman. They remained called by our shared God to continue to love and support me. This sort of supportive spirituality is, I believe, entirely within Lordean philosophy.

Acquaintances have attempted to silence me on every angle, telling me that feminism and faith are incompatible. My living experiences – including those in my mainline Protestant religious faith – have completely contradicted these painful myths. My faith, my feminism, my queerness, and my being poor are not at odds with each other. I must and will continue to speak out, loudly, that this line of thinking is patently untrue.

In closing, I want to leave you all with this message: let our differences strengthen our bond and our reach. Perhaps we were never meant to survive, but if we allow ourselves to be good soil, if we nurture the seeds that Audre Lorde sowed, that The Feminist Wire is sowing, that I am sowing, that each one of you are sowing, we can grow into a field of mustard seeds that is stronger than the silence that tries to stifle the life blooming within us.

“Take our words to bed with you

dream upon them

choose any ones you wish

write us a poem.”

from “Prism” by Audre Lorde

____________________________________________

Mary Kathryn Dean is a graduating senior at Temple University. She studies English Literature with a minor in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Trans* Studies. She is an active member of her church, where she is the coordinator of the Young Adult Bible Study & Fellowship Group, on the Membership and Evangelism Committee, and the LGBTQ Church, Campus, and Community Organizer. Outside (and sometimes inside) school and church, she knits blankets and toys. You can find her on Twitter @marykathryndean.

Mary Kathryn Dean is a graduating senior at Temple University. She studies English Literature with a minor in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Trans* Studies. She is an active member of her church, where she is the coordinator of the Young Adult Bible Study & Fellowship Group, on the Membership and Evangelism Committee, and the LGBTQ Church, Campus, and Community Organizer. Outside (and sometimes inside) school and church, she knits blankets and toys. You can find her on Twitter @marykathryndean.

[i] Audre Lorde. Sister Outsider (Freedom, CA.: The Crossing Press, 1986) : 41

Pingback: Afterword: Standing at the Lordean Shoreline - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire