Queer African Reader: A Review

By Rita Nketiah and Rose Afriyie

In the past decade, African sexual minorities have received increasing attention. 2013 alone saw numerous headlines most notably around the murder of activist Eric Lembembe in Cameroon and the passage of the “Anti-Homesexuality” and “Same Sex Marriage Prohibition” bills in Uganda and Nigeria respectively. But there is much more to Queer rights in Africa than murder and policy advocacy. For example, most mainstream media outlets have been reluctant to include: accounts from queer Ugandans in their own words about the root of African homophobic policy in the Western evangelical movement; the lack of sustainability of lesbian-led nonprofits in Kenya; the marginalization of intersex and trans folks in Uganda; and the fearlessly captured lives of Queer South Africans through photography, to name a few.

In the past decade, African sexual minorities have received increasing attention. 2013 alone saw numerous headlines most notably around the murder of activist Eric Lembembe in Cameroon and the passage of the “Anti-Homesexuality” and “Same Sex Marriage Prohibition” bills in Uganda and Nigeria respectively. But there is much more to Queer rights in Africa than murder and policy advocacy. For example, most mainstream media outlets have been reluctant to include: accounts from queer Ugandans in their own words about the root of African homophobic policy in the Western evangelical movement; the lack of sustainability of lesbian-led nonprofits in Kenya; the marginalization of intersex and trans folks in Uganda; and the fearlessly captured lives of Queer South Africans through photography, to name a few.

For better or worse, there has been much debate and controversy about the place of queer people in African societies. The most heinous of these opinions has been that homosexuality (a term often used to generalize the much more complex sexual experiences of queer-identified people) is an “un-African” ideology superimposed by former colonial powers. In response, many queer Africans and allies have sought to challenge the deeply ingrained gender and sexual norms that continue to threaten the quality of life for non-straight Africans.

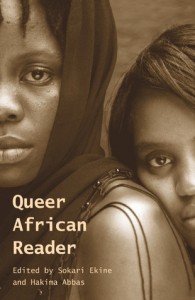

Amidst these debates comes a bold new anthology called the Queer African Reader, published by Pambazuka Press, and co-edited by Sokari Ekine and Hakima Abbas. Indeed, the very idea that one places “Queer” and “African” side by side radically challenges the notion that these identities are mutually exclusive. Understanding LGBTI Africans holistically, not just as newsworthy after vicious murders or after the passage of discriminatory laws, but in their everyday resistance against sexual identity oppression seems within reach. This resolution arrived at in Queer African Reader is especially relevant now as we embark on a new year and new possibilities of envisioning LGBTI Africans and it is important to call out the notable contributions to this effort by name.

David Kato’s essay in the reader is our first foray into Queer sexuality in Uganda, a place where there is a tendency to locate the most extreme forms of homophobia. Instead of simply referencing Kato in relation to his murder, the Reader offers an essay by him written as an act of resistance. Kato is adept at pointing out that the homophobia experienced by LGBT Ugandans – particularly a law that would punish same gender love with the death penalty – stemmed from missionizing work of foreign religious groups and the “global reproduction of homophobia institutionally by American Evangelicals.” This is something especially important to remember as African countries — and not wealthy Christian groups — were threatened with cuts to foreign aid by the United Kingdom and the United States’ vow “to ensure that our foreign assistance promotes the protection of LGBT rights” in the midst of the ongoing struggle for LGBT rights in Uganda.

Kaitlin Dearham discusses the challenges women led queer organizations have faced in the Kenyan context. Perhaps her most compelling critique is around funding and the framework that should be used to advocate for queer rights. The advocacy for human rights, while music to donor ears, often alienated everyday Africans in Kenya whose hearts and minds needed to be won to change the state of Queer rights in Kenya. Her critique also challenges donors to fund local organizing work that may not result in policy advances, or have the most easily demonstrable impact, but is critical for social change.

Awino Okech presents a political challenge for the African feminist community regarding their “conceptual and ideological framing” of feminist agendas across the continent which often excludes the experiences, identities and needs of queer Africans. Okech questions whether, at its root, mainstream African feminism espouses a heterosexist, gender-normative, essentialist bias that ultimately excludes the possibilities of LGBTI alliances. Ultimately, Okech calls for a new feminist paradigm that is both ideological and pragmatic, one that appreciates the LGBTI struggle not merely as a way to “build bridges” across the continent, but as a dismantling of heteronormativity through a radical destabilization of “the family, the state and the economy.”

The work of South African feminist photographer Zanele Muholi is also another important feature of this anthology. As one of few out lesbian photographers on the continent, Muholi’s work provides an important artistic entry into destabilizing heteronormativity in Africa. Muholi’s ability to literally capture LGBTI communities in everyday contexts humanizes their stories. Muholi, herself, adds to this discussion with her own essay extrapolating the main themes in her work Faces and Phases. Notably, Muholi explains that her attempt to capture the diversity in her community through photography which includes “soccer players, activists, scholars, cultural activists, lawyers, dancers, filmmakers, and human rights/gender activists” is a response to the popular victim narrative that often accompanies mainstream depictions of queer life in Africa. Indeed, in many ways, Muholi’s essay embodies the crux of this anthology -that is, the celebration of queer African life through the display of their diverse experiences, emotions and dreams.

However, at the same time that Muholi’s work begins to visually represent the breadth of the LGBTI communities in Africa, this book is self-reflexive, at times turning the gaze back onto itself. Take, for instance, Audrey Mbugua’s chapter “Transsexuals’ nightmare: activism or subjugation?” This essay is a hardline interrogation of the hypervisibility of cisgendered gays and lesbians in the African LGBTI movement. If it is true that mainstream heteropatriarchy neglects queers, Mbugua argues that LGBTI movements have also struggled to incorporate and build with non-cisgendered members of the queer community. A fiery and passionate argument, this essay forces us to listen intently. Indeed, there is a real and justified anger that burns at the heart of this essay, reminiscent of Audre Lorde’s and bell hooks’ earlier works. The essay is very clear in its message, namely, the directive to seriously consider transgender people if we are to have a sustained LGBTI movement on the African continent. They are not, as Mbugua puts it “sacrificial lambs” for the movement. Cisgendered gay and lesbian rights cannot and should not be gained at the expense of transgender people. Progress without a commitment to include the needs of transgender people is not real movement/progress.

Julius Kaggwa’s essay similarly interrogates the heteronormative script that is too often superimposed on intersex people across the continent. The essay’s main contribution is in “challenging the traditional binary sex and gender dichotomy” that currently exists in Africa, which often mischaracterizes intersex people as either having both male and female organs and/or being “bisexual”. Indeed, Kaggwa argues that much of the ignorance surrounding intersex identities is a product of the way we traditionally understand sexuality as (unproblematically) gendered. Add to this that there continues to be a general stigma around sexuality in Africa, which has made it virtually impossible to discuss the complex nature of intersex identity. Kaggwa argues that our inability to have complex dialogues about sexuality in Africa is often what forces intersex individuals to take on other kinds of identities that are more mainstream (i.e. choosing a traditionally designated gender). Ultimately, Kaggwa calls for the re-imagining of intersex identities within queer Africa. Both Mbugua and Kaggwa’s contributions to this anthology begin to take members of this community (and the larger heteronormative society) to task for rendering trans and intersex people invisible in the struggle for equal rights.

The Queer African Reader provides a strong case for the self-reflexivity of LGBTI activists in Africa. Though, like any project, it has it’s limitations. The scope of the book largely concentrates on central and Southern Africa with few contributions from the Western African world. Also, the text is light on personal narratives that focus squarely on everyday love stories that persist despite corrective rape, murder, and stigma. Criticisms withstanding, this anthology is unmatched in its precise attack of patriarchal heteronormativity in Africa. There are very few texts coming out of Africa in the contemporary moment that can boast of the radicalism animating the Queer African Reader. This anthology seeks to turn the gaze back on itself to critically articulate and examine the strategies, motivations and goals of LGBTI movements across Africa. Far from being a stuffy academic text, this anthology, with its eclectic mix of poetry, prose, essays, and short fictions, provides something for every and anyone interested in the interior lives of queer African folk. Include this on your reading list for 2014.

___________________________________________

Rose Afriyie is a civic techie and feminist writer based in Chicago, Illinois. Her writing has been featured in The Chicago Tribune, The Grio and Uptown Magazine. Follow her on Google+ here.

Rose Afriyie is a civic techie and feminist writer based in Chicago, Illinois. Her writing has been featured in The Chicago Tribune, The Grio and Uptown Magazine. Follow her on Google+ here.

Rita Nketiah is a Doctoral Student at the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada, where she is currently studying in Women’s Studies and Migration and Ethnic Relations. Her research interests include Second-Generation African-Canadian identity, gender and sexuality, and the role of Diasporas in (African) Development.

Rita Nketiah is a Doctoral Student at the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada, where she is currently studying in Women’s Studies and Migration and Ethnic Relations. Her research interests include Second-Generation African-Canadian identity, gender and sexuality, and the role of Diasporas in (African) Development.

Pingback: Interesting Articles | Sexual Citizenship