Katniss and Anastasia: Mismatched Heroines in a Shared Hell

By Lucy Berrington

Why does America’s confused cultural gaze keep landing on two such mismatched literary heroines as Katniss Everdeen and Anastasia Steele? One is the badass goddess of The Hunger Games, the other the failed submissive of Fifty Shades of Grey. What can they teach, these two pretend women elevated by so many of us to intergalactic superstardom? What are they for? The more they show up, the less random their implicit pairing feels. And if a purpose of fiction is to hone our skills for real life, for what exactly are Katniss and Anastasia’s fans practicing?

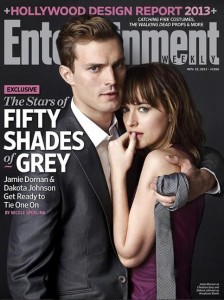

At first sight, these heroines are about as similar as Eleanor Roosevelt and Kim Kardashian. Katniss (now in theaters) shows up trespassing, hunting, and plotting against the tyranny of the regime, an emblem of both female strength and the psychopathic brilliance that underlies The Hunger Games. Anastasia, meanwhile (due onscreen the Valentine’s weekend after next), battles the foremost enemy of the privileged modern woman, her hair (“I must not sleep with it wet. I must not sleep with it wet”). Katniss (at least in the book) is racially ambiguous, Anastasia predictably Caucasian. Katniss has learned to wear an “indifferent mask” to conceal her various thought crimes. Anastasia smirks, rolls her eyes, flushes and cringes, often for no discernible reason except embarrassment at being in the wrong book. We can only wish she’d indulge in a few thought crimes of her own (she is, after all, afforded every opportunity).

At first sight, these heroines are about as similar as Eleanor Roosevelt and Kim Kardashian. Katniss (now in theaters) shows up trespassing, hunting, and plotting against the tyranny of the regime, an emblem of both female strength and the psychopathic brilliance that underlies The Hunger Games. Anastasia, meanwhile (due onscreen the Valentine’s weekend after next), battles the foremost enemy of the privileged modern woman, her hair (“I must not sleep with it wet. I must not sleep with it wet”). Katniss (at least in the book) is racially ambiguous, Anastasia predictably Caucasian. Katniss has learned to wear an “indifferent mask” to conceal her various thought crimes. Anastasia smirks, rolls her eyes, flushes and cringes, often for no discernible reason except embarrassment at being in the wrong book. We can only wish she’d indulge in a few thought crimes of her own (she is, after all, afforded every opportunity).

Switch them, and both stories fall apart.

Katniss dashes naked across the Red Room of Pain. She shimmies up the bedpost and climbs into the iron grid suspended from the ceiling. Barely has Christian Gray offered up a friendly pair of handcuffs when our heroine lands a well-aimed spike in his heart.

Fifty shades, perhaps, but no more than half a dozen pages.

The Hunger Games with Anastasia bombs, too. As the game begins she stands on her metal circle at the Cornucopia, biting her lip and flushing at the bloodbath before her. Holy crap! This wasn’t in the contract! And so this child-woman flees sobbing (like she does). One shudders to imagine the character that fell headfirst into Christian Gray’s office making her entry into the gamemakers’ deranged forest. Anyway, it’s hard to weep for a heroine who’s mortified that her lover knows she menstruates.

Part of the difference belongs to their respective audiences. The Hunger Games was written for teens and young adults. Katniss is the fantasy of women who haven’t yet been crushed by life (may the odds be forever in their favor). She’s self-sufficient, discriminating with regard to who receives her emotional resources, and retains her integrity despite mortal pressure to fall in with the world’s heinous plan for her.

For Fifty Shades, we must look largely to women over 40. How I despair of us. Our incoming heroine is physically stunning, free of stretch marks and regret, surely years away from her first mental health prescription or that awkward moment when her uterus flops onto the sidewalk. To the people who matter, her various ineptitudes cannot mask the muse within. Yet Anastasia is also a man’s woman: no sexual history, no gag reflex, and just assertive enough in the bedroom that he needn’t feel like a rapist. Through this lens, my generation seems tormented. Michelle Obama said she hadn’t time to read Fifty Shades (I know, right?), adding, “but it’s obviously tacked into something, and [is] giving people permission to explore parts of themselves that maybe felt a bit taboo.” Maybe Michelle Bachman and Sarah Palin discreetly downloaded it to their tablets, those women whose social world is all about taboo. Their explorations can now be made digitally — technology, not fingers, people! — with lowered risk of moral exile or psychic boot camp, solutions that seem so popular over there.

We don’t know the racial demographics of the books’ respective readerships, or to what extent the success of their heroines is owed to white fans versus fans of color. But the combined popularity of these two stories is such that questions must be asked. Again, why? As Paul Bloom, the Yale psychologist, says in his book How Pleasure Works, fiction is a means of practicing for real life. We’re drawn to dramas about the zombie apocalypse not because we expect a zombie apocalypse but because “even these exotic cases serve as useful practice for bad times, exercising our psyches for when life goes to hell.”

For what kind of sadistic hell are fans rehearsing via Katniss and Anastasia?

In the movies, both these heroines are white — controversial in the case of Katniss, but not surprising in the context of our dominant cultural preferences. (America is taught to empathize more readily with white people and is more likely to anoint them icons.) Too, both of these heroines are young, beautiful virgins offered up into a soulless landscape for the amusement of people who get off on inflicting pain. Each struggles to hold onto a smidgeon of power in circumstances designed to strip it from her entirely. They are hard-pressed to unravel the motivation of their respective men: romantic partner or perilous threat? And each has landed where she didn’t need to be: Katniss volunteers for the Hunger Games to spare her little sister a fight to the death, Anastasia fills in for her BFF at an important interview with a fine young billionaire — acts of selflessness that launch them into their terrible unknowns. (Lesson: trust no one and nothing, not even your own values.) There is overlap, too, in their family circumstances. Both lost their fathers early in life. Katniss has grown up with a traumatized, catatonic mother, while Anastasia’s mom is bored, has “the attention span of a goldfish,” and is into candle-making, which sounds a lot like traumatized and catatonic to me.

And then there’s the shared mystery of our heroines’ lost libido — a conceit facilitated by their whiteness (in Katniss’s case, onscreen), with its unearned connotations of sexual purity. Anastasia doesn’t have a sex drive until the creepy billionaire shows up, Katniss hardly at all. Many commentators’ hands have wrung over the regressive message embodied by Anastasia, the notion that women can’t enjoy wild fringe sex unless their wild fringe guys fall in love. Actually, not even then. The obvious lesson of Anastasia is that readers should be demanding better quality erotica. The not much less obvious: twenty-first century notions of female sexuality remain inane, and our judgment of ourselves and other women should be all the kinder for that.

Katniss’s lack of sexual desire is no less troubling for seeming self-willed. And is it really? In her world, sex brings the risk of giving birth to children who will be reaped and slaughtered. And yet she fears the president will require that she have them, just as he orders her marriage. Here, the well-being of sexually active women is no longer in their own hands but the state’s — a state that can maneuver women into conceiving and delivering babies they aren’t ready for and didn’t choose, and into marriages that might seem to justify those babies but can’t provide for or protect them. It’s a state that eagerly punishes children for the poverty, hunger, and the lack of self-agency it imposes on their parents.

Well. That’s not sounding completely unfamiliar. It isn’t so hard to visualize a state in which leading players relentlessly restrict women’s access to legal abortion and birth control, attenuate the definition of rape and appear to defend it as a method of conception, obsess about the fertilized egg yet disdain the impoverished child it becomes, promote “traditional family” as the solution, and ensure that alternative futures for disadvantaged women are pretty much unattainable. Now the state’s betrayal of Katniss Everdeen does not seem so abstract and fantastic.

Katniss and Anastasia are two of America’s heroines — women grappling with extreme physical self-sacrifice. Their minds and bodies are at once thoroughly and inadequately female and their physicality not their own. How unexpected these two seemed at first, back when they had the power of surprise. And how quickly they turned into women we’ve always known, have sometimes been, or might become.

______________________________________

Lucy Berrington is a British-American writer, health communicator, and despairing feminist, living in Boston, MA. Her reporting, commentary, and fiction have appeared in US and UK publications including The Guardian, The London Times, Marie Claire, The Daily Beast, Brain Child, Ms (online), and the New England Review. She blogs on autism at Psychology Today. Follow her @LucyBerrington.

Lucy Berrington is a British-American writer, health communicator, and despairing feminist, living in Boston, MA. Her reporting, commentary, and fiction have appeared in US and UK publications including The Guardian, The London Times, Marie Claire, The Daily Beast, Brain Child, Ms (online), and the New England Review. She blogs on autism at Psychology Today. Follow her @LucyBerrington.

Pingback: quick hit: Katniss and Anastasia: Mismatched Heroines in a Shared Hell - feimineach

Pingback: Katniss and Anastasia: Mismatched Heroines in a Shared Hell

Pingback: Quick post: A few good links | On Memory and Desire