#BlackPowerIsForBlackMen: Letters from Brothers Writing to Live

By Brothers Writing to Live

We are a collective of black men dedicated to challenging the ideas of black masculinity and manhood through the written word. Through our work, we explore the ugliest parts of ourselves and our community, in the hope that we can illuminate the beauty that we know exists as well. We challenge each other daily to create and be more than what this racist, patriarchal society has raised us to be. But simply wanting it will not do. It requires tons of hard work, and much of that work includes listening to our sisters, black women, who tend to bear the brunt of our messiness. Unfortunately, in this regard, we have been woefully absent.

We are a collective of black men dedicated to challenging the ideas of black masculinity and manhood through the written word. Through our work, we explore the ugliest parts of ourselves and our community, in the hope that we can illuminate the beauty that we know exists as well. We challenge each other daily to create and be more than what this racist, patriarchal society has raised us to be. But simply wanting it will not do. It requires tons of hard work, and much of that work includes listening to our sisters, black women, who tend to bear the brunt of our messiness. Unfortunately, in this regard, we have been woefully absent.

When the hashtag #Blackpowerisforblackmen, created by Ebony.com editor Jamilah Lemeiux, took over Twitter, it was a clear sign that we haven’t been doing enough. Thousands of our sisters (and brothers) tweeted for hours about the imbalance in our community. We, black men, tend to pride ourselves on our anti-white racial supremacy activism but often fail to reach out and consider the pain and trauma faced by the women in our lives. Our culture actively denigrates the very existence of black women. We take their love, support, nourishment, and spiritual presence for granted. As a whole, black men have not reciprocated our love and support in a way that affirms the humanity and dignity of black womanhood in the face of white supremacy, patriarchy, heterosexism, homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, sexual violence, and physical and verbal abuse.

When the hashtag #Blackpowerisforblackmen, created by Ebony.com editor Jamilah Lemeiux, took over Twitter, it was a clear sign that we haven’t been doing enough. Thousands of our sisters (and brothers) tweeted for hours about the imbalance in our community. We, black men, tend to pride ourselves on our anti-white racial supremacy activism but often fail to reach out and consider the pain and trauma faced by the women in our lives. Our culture actively denigrates the very existence of black women. We take their love, support, nourishment, and spiritual presence for granted. As a whole, black men have not reciprocated our love and support in a way that affirms the humanity and dignity of black womanhood in the face of white supremacy, patriarchy, heterosexism, homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, sexual violence, and physical and verbal abuse.

#Blackpowerisforblackmen became the call, and as black men dedicated to fighting alongside our sisters, we have taken up the responsibility of answering. As individuals, we recognize where we have fallen short, and as a community we make a promise to participate in deep self-reflection and correction.

This ain’t just an apology; it’s a commitment.

Dear Monifa Bandele (@monifabandele), You tweeted the following: “#blackpowerisforblackmen when trying to discuss gender privilege is black male bashing.”

I had one of those moments like the old folks do in church where all I could do was sway and say to myself “well ain’t that the truth.” It’s most disheartening because a quick glance at our past or present shows us just how dedicated black women have been to addressing the black men in this country. But when sisters speak up and ask us to consider the ways in which we have contributed to their oppression, we consider it an affront to our fragile sense of community and an attack on our manhood.

Undoubtedly, there were the brothers reacting with the predictable “not me!” responses. But those individual “not me’s!” aren’t enough to drown out the massive indifference to black women’s suffering at the hands of black men. We defend to the hilt the culture we’ve created around a toxic vision of masculinity, but can’t muster up a tenth of that energy to get into the streets and demand our sisters stop being raped, and then we pretend we don’t know what privilege is.

I heard one brother flat out say sexism isn’t the problem in our community. If ever there was a moment we could use a drop squad, that was it. We can pretend away the sexism and misogyny we inflict upon black women. We mirror the worst of the defense of racism when we do and enact untold damage to the bodies and psyches of the women who have loved us most. We can stand back and pretend, as black men, we’re the only ones under attack, as we’ve done, or we can acknowledge our culpability in oppressing black women and dedicate ourselves to striving for better. The choice should be clear.

Dear @YoloAkili, “#BlackPowerisForBlackMen Becuz I can’t think of ONE national march that black men organized becuz a black woman was raped or killed.”

I must have reread your tweet a hundred times today. I understood fully, maybe for the first time, that black men who profess a love for black women can’t have it both ways. The truth is too true and the stakes are too high. We can’t, as I did, call Kendrick’s verse one of the dopest lyrical performances of the year when the song is bubbling with spectacular disses of black women and black femininity, then wonder why we never organized around the killing or rape of a black woman.

We can’t watch and participate in the national obliteration and shaming of Rachel Jeantel and wonder why we never organized around the killing or rape of a black woman. We can’t lie, cheat on, or manipulate black women while convincing black women it’s so hard for us then wonder why we never organized around the killing or rape of a black woman. We can’t literally and figuratively kill and rape black woman for fun, for free, for checks, for claps from our niggas, and wonder why we never organize around the killing or rape of black woman.

No art, no person, no relationship, no sexual fantasy that kills and rapes black women is going to stop black women from being killed, hurt, and raped. If our consumption and creation doesn’t affirm, accept, and explore the complicated lives of black women, we can’t be bout that life. No exceptions. Never. Shameful that after all this life, and education, and art creation, your tweet made me know that we really ain’t been bout shit. We really been encouraging black women’s death while leaning on black women for survival. Sorry ain’t enough.

Kiese (@KieseLaymon)

_________________________

Dear @PrestonMitchum, “@PrestonMitchum: #blackpowerisforblackmen because as sad as it already was, what if Trayvon were a woman?”

What if Trayvon were a woman? After reading your tweet, I contemplated that question for hours. I thought about everything I read about Trayvon Martin. I thought about all the conversations I had about Trayvon Martin. I tried to remember similar conversations about female-identified individuals. They really didn’t exist. And when they did, they were framed in the context of blaming the victim for something “she” should have done to prevent the horrendous actions perpetrated against her. If Trayvon were a woman, the story would have been told though the lens of a male because our society always allows men to speak for women, believing this act gives women a voice. We have yet to truly move past ideas of coverture and do the work to train our sons, husbands, brothers, and male friends to view women not as property but as equal partners.

The silencing of women is so deafening that even in life and death we want to dictate the terms of how a women can give life or how we would tell her story in death. I don’t profess to understand the myriad ways my male-privilege continually operates to suppress and oppress women but I can celebrate all women and I can do the work to love women as Rainer Maria Rilke teaches. — “Love is the commitment to be the witness to someone else’s joy in life, not to be that joy.”

Wade (@Wade_Davis28)

Dear @Blade_Varzity, “#blackpowerisforblackmen Can someone explain exactly how BM are stopping BW from addressing ANY of these issues they’re tweeting about?”

Blade, I have come to realize that sometimes we as people,who exist on the scale of oppression (I am a Black man of immigrant parentage from a ghetto in Brooklyn who spent 1/3 of his life in prison), are so easily blinded by our own marginalized place on that scale that we are unable to see how we contribute to the oppression of others. I say this not as an indictment on you in any way, but as an expression of understanding and realization of the shrewd nature of the hierarchy of oppression and our subconscious infatuation with our own oppression.

Blade, I have come to realize that sometimes we as people,who exist on the scale of oppression (I am a Black man of immigrant parentage from a ghetto in Brooklyn who spent 1/3 of his life in prison), are so easily blinded by our own marginalized place on that scale that we are unable to see how we contribute to the oppression of others. I say this not as an indictment on you in any way, but as an expression of understanding and realization of the shrewd nature of the hierarchy of oppression and our subconscious infatuation with our own oppression.

As Black men in a patriarchal, white supremacist world it’s so easy not to realize our own male privilege because in comparison to white male (and female) privilege, we think our whatever-privilege is minuscule. But, however minuscule, it DOES exist, particularly in the eyes of Black women, and especially when we, black men, don’t acknowledge our role in their oppression as Black Women.

Like I said Blade, this is not an accusation just an observation. Peace, bruh.

Marlon (@marlon_79)

_________________________

Dear Yolo Akili Robinson (@YoloAkili), You tweeted the following: “#BlackPowerisForBlackMen becuz even in the Black LGBT community MALE voices (cis/trans) r still privileged over all women&genderqueer folks.”

Damn, bro! Your words hit me hard—in the best way possible.

I am a gay black man who has been skilled at calling out white racism and heterosexism as weapons that have stifled my own senses of freedom. I even try to do the type of self-work necessary to understand my complicity in sexism and the part I play in maintaining the patriarchy, but I know that I can do and be better.

I can do better at not only calling out sexism, misogyny, transphobia, rape culture, and so much else, but I can be a better brother to my cis and trans sisters (regardless of their sexual identities) by not taking up too much space (when I know that some spaces are often made available to me precisely because I am a black gay cis man). That is the work, my work, for sure.

I can do better at not only calling out sexism, misogyny, transphobia, rape culture, and so much else, but I can be a better brother to my cis and trans sisters (regardless of their sexual identities) by not taking up too much space (when I know that some spaces are often made available to me precisely because I am a black gay cis man). That is the work, my work, for sure.

We black gay men have models of the “better,” however. My brother Kai M. Green (@Kai_MG) reminded me that some of our black gay male elders (who, too, benefited from the unearned privilege of maleness) worked hard to think and practice feminism. Kai tweeted: “#blackpowerisforblackmen bcuz we 4get Joseph Beam and Marlon Riggs were Blk feminists 2. Feminism isn’t just for cis women–>we ALL need it!” Yes, feminism is for all of us. I am in community with women I can learn with/from, remain accountable to, and engage transformative personal and social justice work alongside. I want my sisters and critically conscious brothers, as my brother Kiese once wrote, “to knock my hustle” when need be. I will do the same for you and others. That is the only way I can grow. The only way that we can be better. The only way that I/we might truly show up as allies in the struggle to end patriarchy, the power-driven reign of “the man” (and not just the one imagined as white, but also the one who stares us black men back in the face when we look in the mirror).

Darnell (@moore_darnell)

________________________

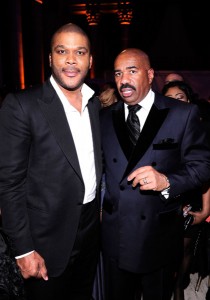

Dear Raequel Solomon (@systris2h), “cause tyler perry and steve harvey are deemed worthy of telling US how we should be living? #blackpowerisforblackmen”

Your tweet is complicated and my feelings towards both Tyler Perry and Steve Harvey are as complicated. I’m assuming the “US” that you are referring to is black women; but even if that isn’t the case, the black community at large is still deeply affected by these two men and the public platforms they occupy. I don’t know who is deeming Perry and Harvey as “worthy” and again, I’m assuming because of the hashtag that accompanied your tweet you may have meant black men are. But I’m completely convinced what is responsible for this “christening” of Harvey and Perry’s black sagaciousness is not a population, but an institution and a doctrine.

Black living is messy and difficult and is more trial and error than anything else. Anything or body that says otherwise is standing on the side of black powerlessness as opposed to black power. What is also crucial in my conceptualizing this tweet is the context that black media has carved into this moment of post-racial hopscotch and difference’s reduction. The sheer number of black faces and spaces in American media is slim to none and the ability to choose with a convicted agency is placed in jeopardy as a result. But a choice is nonetheless being made.

It would be misguided and misinformed to approach this tweet without sensitivity to gender’s role in producing it. Yes, Steve Harvey and Tyler Perry are black men and, yes, black men have participated in the patriarchal tradition of speaking for and over black women, but issues of hegemony and capitalist seduction aside, the consumers of products made by these two men make a choice to support their products and never should we, as black people, attack the people choosing or producing the product, but instead the product itself. Bottom line is this – the interrogation of the function and usefulness of the tangible products that make up a black social reality is a fundamental method to form and maintain black power in this profit-driven, privately influenced market we know as America.

Peace,

Hashim Khalil Pipkin (@ablkCharlieBrwn)

___________________________

Dear Charlene Carruthers (@charlenecac),

You tweeted, “#blackpowerisforBlackmen because Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington and Denmark Vesey would never end up in a sex tape spoof.” You also tweeted, “Uncle Rush and Co. didn’t just pick a nameless black woman. They picked our ‘Black Moses.’ The gun wielding guide to freedom.”

You made me revisit Audre Lorde’s call for women to make use of the erotic as a source of power, a source of power that because of patriarchy, misogyny, and white supremacy has been deemed solely pornographic. There is power in the erotic—it is a site of reproduction, a site of intimacy (intimate relationships with lovers, intimate relationships with kin, intimate relationships with violence, loss and death), and a site of struggle. The erotic terrain is a site of embodied knowledge. That Black men like Uncle Rush and Co. feel it is funny to make a sex tape starring Harriet Tubman is violent and sick. They went back and sexually violated a historical figure and then disappeared the evidence (the video), but the deed was done and those ghosts will continue to haunt us like so many other “nameless Black women,”–-we must speak up. The struggle that Black women have had and continue to endure in order to gain access to their erotic power is real.

Although Audre Lorde’s call was to women, it is clear that men, Black men especially, need to interrogate the erotic as well (Thank you Alexis Pauline Gumbs for this lesson). The erotic for Black men has been distorted by a violent type of pornography perpetuated by Black men as well as others—it is the notion that Black manhood is only fully realized when men through domination take control of their houses, their women, and their stuff. The erotic as a source of knowledge cannot be fully reached until we, Black men, let go of our ideas about reclamation of some ideal manhood that was taken from us. We must let go of manhood as ownership. We spend so much time trying to reclaim some sense of humanity through manhood that we don’t see how we become the oppressors in our quests to reclaim.

If we could only realize that everything we need, we have. But then that is scary, because what is it that Black men have that we don’t want to face? Lorde stated that the erotic “lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane.” Hortense Spillers says, “It is the heritage of the mother that the African-American male must regain as an aspect of his own personhood–the power of the ‘yes’ to the ‘female’ within.”

For Black men to really be able to interrogate the erotic, we must face the real truth of our vulnerability, too. Because though we will not see a sex tape spoof of Booker T. Washington, we know that historically and in the present day, Black men’s bodies also archive dis-(re)membering sexual traumas. We too were made to bend over and open up, taking in whatever the master decided to feed us that night. But if we cannot face that in ourselves and in our bodies because we only see it as emasculation, then we lose our erotic power. We lose the power to unite with Black women. We lose the power to ultimately unite with our full selves. We lose the power to analyze the ways in which we become oppressors because we are no longer able to see Black male privilege–we only see white racism and white men. We reach for that white power not realizing we have access to something much greater, much more generative, right here in our own bodies as Black men.

Black men need to do as Hortense Spillers says and interrogate that being that we are encouraged to despise, the being that we fear will destroy our manhood, that Black woman that lies deep in us—this strength is also this vulnerability.

We are not enemies, Black men and women. Black men need to recognize that critique is love. Love asks us to grow. We need to grow.

I want you to trust me.

I understand that the love of a Black woman is a privilege often times devalued, but I value you and your love. I value the love of Harriet Tubman. I value the love of my mother—Black love, tough love, deep love, mama love, granny and auntie love, lover love, sweet potato pie love, I’m tired from working all day love, get the holy ghost and pass out love, get school clothes for baby while you still wear that same ol’ raggedy dress and make it look good love, stay up all night and watch over me when I’m sick love, I’m tired of yo’ triflin’ ass I’m leavin’ love, I’m hurt love, I’m exhausted but I’m still gonna make you dinner love, You locked up so I’mma hold it down for you love, gansta love, Black professional don’t have time to cook but let’s share a glass of wine love, I will carry your stash love, I will go down on your behalf love, I will testify in court love, young love, hot love, you getting on my nerves love, love love, Black women’s love is God love.

I will do my part to reflect that love. I will hold you when I am strong and when I am weak. I stand with you. And I vow to you that no quest for freedom of mine will begin with the devaluation of your body, spirit or intellect. I vow to listen to you. I vow to stay open to being checked, but I will not wait on you to check me. I will work to check myself too, because I understand that feminism isn’t just about your liberation, it’s about OUR liberation. If my manhood becomes a placeholder for my humanity, we are doomed. But I want to live, love.

<3Kai (@Kai_MG)

______________________

Brothers Writing to Live is a group of black cis and trans-men who hail from spaces across the United States. We come from myriad neighborhoods, diverse familial backgrounds, and different life worlds. We are different, indeed. And, yet, in so many ways we are the same. We are black male identified writers whose notions of blackness, manhood, and writing are as assorted as our multifaceted lives. Whether we have come from the red clay roads of Mississippi or the cement paved streets of New York City, through our writings we have mapped out similarities regarding the ways that racism, gender restrictions, capitalism, heteropatriarchy, ableism, economic disenfranchisement, heteronormativity, criminal (in)justice systems, and so much else has shaped the men that we have become and yet to be. This campaign has united the following black male writers:

Kiese Laymon, Writer & Professor at Vassar College

Mychal Denzel Smith, Writer, Mental Health Advocate, & Cultural Critic

Kai M. Green, Writer, Filmmaker, & Ph.D Candidate at USC

Marlon Peterson., Writer & Youth & Community Advocate

Mark Anthony Neal, Writer, Cultural Critic, & Professor at Duke University

Hashim Pipkin, Writer, Cultural Critic, Ph.D. Candidate at Vanderbilt University

Wade Davis, II, Writer, LGBTQ Advocate, & Former NFL Player

Darnell L. Moore, Writer & Activist

Pingback: You aint funny or cutting edge: A letter to Jason Horton | Dr. David J Leonard

Pingback: Daily Feminist Cheat Sheet

Pingback: Black Power Is For Black Men, an Uppity Negro Editorial Response | Uppity Negro Network™

Pingback: Women’s Equality Day 2013: Celebrating the nostalgia of past successes while remaining rooted in the dangers of the future | Jasmine Burnett