Why My Kingdom Needs Janelle Monae’s Q.U.E.E.Ndom

By Hashim Pipkin

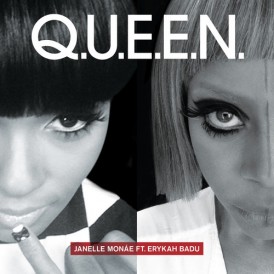

I am not a black woman. And unlike many who are not, I do not claim to be able to speak for the quotidian existence of black women in this world. I do not know their interior lives. I do not know the battles their desires must take up daily to keep intact their psychic and emotional survival. But as a brother to a black sister, a son to a black mother and a best friend to a black woman, I do know that we are responsible to and for each other. Janelle Monae reminded me of that in a very urgent way with her newest single, “Q.U.E.E.N.”

I am not a black woman. And unlike many who are not, I do not claim to be able to speak for the quotidian existence of black women in this world. I do not know their interior lives. I do not know the battles their desires must take up daily to keep intact their psychic and emotional survival. But as a brother to a black sister, a son to a black mother and a best friend to a black woman, I do know that we are responsible to and for each other. Janelle Monae reminded me of that in a very urgent way with her newest single, “Q.U.E.E.N.”

Janelle Monae might be reduced to the “girl who wears tuxedos” by those who are distracted by her nuanced branding, but she and her creative production are representative of so much more than “costuming.” We were told in her acceptance speech at this year’s “Black Girls Rock” ceremony, that actually, those tuxedos are performative reminders to Ms. Monae of a tradition and ethic of prideful work she witnessed through her parents. They wore uniforms to perform labor within a society that undermined the genius residing in them. Janelle Monae is conscious of this past and of its implications for her career–a career that, at one time, would seem alien to many black folk who labored just for a baseness of life. So – the bow ties, the tuxedos, the shoes are not only components of a uniform, but visual acknowledgements of her responsibility to continue that too often forgotten tradition of dignity native to the black working class experience.

Janelle Monae’s “Q.U.E.E.N” is in keeping with that same commitment to conversation with the black past and future. Rebellious percussion, tender jazz horns and an electric hip-hop pulse define the single’s sound. The power of this track gets some assistance from Erykah Badu’s hypnotizing alto voice and of course, the colossal sermon created by each lyrical verse.

Social media ignited seconds after Monae premiered the video for her single on BET’s 106 and Park with, admittedly, one of the most memorable lines from the song – “the booty don’t lie.”

This line matters to me not because of its catchiness or taboo nature, but because it is a deliberate reclamation of black women’s bodies as texts of triumph. This line is more litany than lyric. When trying to reconcile the multi-directional assault that comes against the bodies of black women and America’s commodification of them, I feel helpless. The narratives of Sarah Baartman and so many other brown and black women rush to my heart and what was once helplessness soon turns to indignation. And I’m glad to know Monae’s song had a similar instinct. Each time the line, “the booty don’t lie” is heard, it is connected to references of acts of resistance:

This line matters to me not because of its catchiness or taboo nature, but because it is a deliberate reclamation of black women’s bodies as texts of triumph. This line is more litany than lyric. When trying to reconcile the multi-directional assault that comes against the bodies of black women and America’s commodification of them, I feel helpless. The narratives of Sarah Baartman and so many other brown and black women rush to my heart and what was once helplessness soon turns to indignation. And I’m glad to know Monae’s song had a similar instinct. Each time the line, “the booty don’t lie” is heard, it is connected to references of acts of resistance:

This joint’s for fights unknown/Come home and sing your song/But you gotta testify/Because the booty don’t lie

Well I’m gonna keep leading like a young Harriet Tubman/You can take my wings but I’m still goin’ fly/And even when you edit me the booty don’t lie.

These excerpts are indicative of the very specific posture of resistance crucial in trying to make sense out of a marginalized existence. That posture must always be in-between. It must float in and out of history, struggle, and progress. Yes – sing, but be willing for your art to be testimony. Sure – lead, but be willing to lead with thought even when physically unable. “Q.U.E.E.N” challenges us in the midst of unknown fights and a censored truth to testify, lead and fly wingless because the weight of such truth assembled by living on the margins is enough. That type of truth cannot lie. It cannot be domesticated in the service of unifying fantasies of neat and rigid identity formations. And we must be willing to nurture this radical practice of truth-telling and truth-keeping in all moments of life – be that the moment when a daughter’s tears from her mother’s sharing of her story of rape begin to fall uncontrollably, but deliberately, or the moment that the drip of sweat from blissful dancing with girlfriends arrives on her upperlip, or even the moment when the moon’s starshine tenderly gleams at the goodnight kiss exchanged between women who love each other intimately.

I am convinced of one thing every time I hear “Q.U.E.E.N,” and that is the wholeness of black folk in this country is entangled in one another. That’s a horrifyingly comforting thought because that requires relentless labor– something to which, as evidenced in the logic of her aesthetic performance, Ms. Monae is completely committed to. Her Q.U.E.E.Ndom is built on beautiful resistance to capitalist driven sexual politics, misogyny, homophobia and sexism. And it just so happens that whatever kingdom becomes the product of my or any other black man’s imagination will only be worth naming as such if it stands against those same societal ills. This accountability to one another will ultimately protect each other. Protection is the first step to peace.

I can get down with that.

_________________________________

Hashim Pipkin is a writer, teacher and culture critic. He is interested in black sexual politics, black social ethics and the application of Marxist and queer theory on American popular and material culture. He is a former public school teacher, educational administrator and National Endowment for the Humanities Scholar. He is an honors graduate of Georgetown University and also the recipient of the Robert W. Woodruff Fellowship at Emory University. He is a Ph.D. Candidate in English at Vanderbilt University. He is at work on his first collection of essays, Surely Free: Black People and Love.

Hashim Pipkin is a writer, teacher and culture critic. He is interested in black sexual politics, black social ethics and the application of Marxist and queer theory on American popular and material culture. He is a former public school teacher, educational administrator and National Endowment for the Humanities Scholar. He is an honors graduate of Georgetown University and also the recipient of the Robert W. Woodruff Fellowship at Emory University. He is a Ph.D. Candidate in English at Vanderbilt University. He is at work on his first collection of essays, Surely Free: Black People and Love.

Pingback: Janelle Monae | Theresa Anderson Art

Pingback: Janelle Monae | Theresa Anderson Art

Pingback: Janelle Monae | Theresa Anderson Art

Pingback: Janelle Monae | Theresa Anderson Art