Woman's Work

Depending on the promise, girls pack differently. Girls from the north, known for their beautiful pale skin created out of long winters will pack their resignation. After all, with every bad harvest, their older sisters had left, one by one. That’s how it’s been for many generations. That’s how it worked up north, where the most valuable things that a family could own were girls; girls who would leave the land if they were to marry, but who could be sold for 500 yen if she were average looking, 1000 yen if she were beautiful. And these girls were known to be good girls, good workers, who would serve their masters as they did their own parents: faithfully, without complaining.

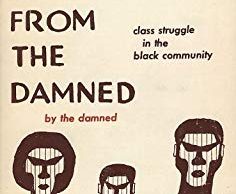

Singapore Japanese Cemetery: Nearly 200 Women are Buried. Average Age of Death: 21.6 years old (Photo by author)

Besides, the girls tell themselves; besides, their parents tell themselves and their daughters: This is how it has been after every bad harvest: girls in a dozen herded out of the villages heading south to Tokyo where they would work as long as their contracts lasted. And girls knew that this year, with the failed crop during the harvest time (too cold of a summer, too hot of a summer, that one day when it rained too much and drowned the newly planted rice, it did not matter, it seemed as if they just could not have good harvest here), with no more girls left to sell (the ones still there were too young, too old, too slow, too ugly), it would be their turn. Their parents had nothing to sell, and in this society, where everything had to be paid with money, that was the only thing that mattered: cash. So wordlessly, girls gathered to a place where they were told to go, with a smallest bundle pressed against their bodies, as if they were protecting something from being stolen. They stand early in the morning for the procurer to arrive to take them to the cities. It is only a short time, they tell themselves quietly: it is only a short time, and I can come home.

In another part of the country, close to Tokyo, girls would pack their hopes and dreams, and perhaps the future could come true in America. These were girls from Kanagawa who heard about their neighbors who had crossed the Pacific Ocean and now lived in a house being served by white servants surrounded by trees that bore money as their fruits. After all, that’s what they said about America, and the neighbors with their sons and daughters in that land all lived in the biggest houses, not the kind of houses that could be built by hands of sharecroppers as their parents’ were, but houses that only landlords could build. The men and women dressed in American cloth, adorned in gold chains and earrings, all wearing the cleanest hats and wearing fur coats even at the hottest season. How they walked around the village as if they owned the place now that they were rich. And they were, compared to poor farmers. And how these women and men looked at you, with yearning, with intimacy so unfamiliar (but then they lived in America, which made them more friendly, less formal than people should be in Japan, that’s what they said about Americans). And when they told the girls about America, America, the place where anyone can be rich, where mountains are gold, where even small children carried silver coins in their pockets, and that people could go to schools and learn (and even girls can go to universities if they work for a short time – why, some of the Americans even let their maids and gardeners go to school even while working), and make something out of their lives. Maids. Working as a waitress in a Japanese restaurant. Laundry shop. So many options. And girls listened with their mouths open, just like chicks being fed worms by the mother bird. Girls listened with all their hopes and possibilities held out in front of them, and all they had to do is to pack and follow these rich people to Yokohama, where the ships awaited to sail them across the ocean to San Francisco, to Vancouver, to Seattle, to Honolulu. That’s where dreams could come true. That’s where dreams did come true.

The girls from Amakusa Island and Shimabara Peninsula packed acceptance and even understanding about their lives, because promises were made that they would work for a few years, just like others on this land had done, and could come back to build the biggest houses with the money they earned and saved; that on the land they call home, where houses are built on the narrow flat strip of land between the sea in front of them and the mountains behind them, where nothing grew but taxes were still the same, where the fisherman could only go so far into the sea before they would get lost in the vast expanse between the water and the sky, that people got on the boat to Nagasaki, only some miles away, to find work for many generations. Around here, their families were never whole but always fragmented, their fathers or mothers working somewhere outside of the islands, maybe the older brother or a sister missing: men have gone to Nagasaki to work as porters, day laborers, works that demanded no education and every piece of their muscle in exchange for money to send home. And women as nannies. Maids. Prostitutes. Selling sex – around here, they called it “woman’s work,” and they knew that bodies were commodities, portable, followed them wherever they went, and did not need training or education. If men had to sell their bodies for labor, so did women for sex. For many generations here, boys and girls could explore each other sexually as soon as their bodies matured, and no one thought anything wrong with it. It was just the way things were, as much as men and women left to work outside as soon as they were old enough to earn money. Lifting coals into ships. Carrying boxes and luggage. Pulling rickshaws. Selling sex. Either way, it was work. Work that gave them money, money they could send home every year, work that would allow them to go home with their heads held high and their families saved from starvation. Men’s work, women’s work. What others did not want to do, they did because it was work and nothing else. So they took the small luggage and followed the procurers to Nagasaki, where the ships took them north to Vladivostok, to Pusan, or boats west that took them to Shanghai where Nagasaki people went “as if to go to a barber,” where they did not need passports, and from that port to Hong Kong, Hanoi, Singapore, Thursday Island, Bombay, Rangoon, Manila, and as far away as Madagascar, Mozambique, and Cape Hope in South Africa. Anywhere there were more male laborers and no place for wives, where men needed sexual releases because they could not bring their wives, where there were moneys to be made for migrant laborers who would barely be earning enough to sustain the basics: food, shelter, and sex.

* * *

When the proper women started to come, that’s when we are driven out. It is always the same everywhere: in Butte, in San Francisco, in Singapore, in Hong Kong, in Seattle, in Australia, in Shanghai. When white women come riding in their horse-drawn carriages, the collars of their dresses drawn high up to hide their necks, and alight in their boots, men, who could not get enough of us, suddenly pretend that we are no longer here, and soon enough, they tell us to move our businesses somewhere else, somewhere far away, but I can hear their wives whispering in the ears, “Those women, those women have to go.” And men nod. They nod and nod, while they come to see us at night when no one can see them, and do things to us that they would never do to their wives. From behind. Us on top. Talking dirty. Pinching our nipples. Sometimes crying. Sometimes just talking, talking about everything and nothing, and we just nod next to them because we don’t understand what they are saying, because we don’t care. Chinese women in beautiful cheongsam, silk dresses embroidered with flowers and patterns, their hair perfectly shaped despite the humid heat in Singapore, alight off the rickshaws, walking around the Raffles House chattering like freed birds while we sit behind a barred doorway in the dim light, and they do not see us. Men thirst for women – especially our kind when there are not enough women around – but the moment the properly dressed women alight off the train, the trains these men built with their bare hands, alight off the rickshaw that they themselves pull, or the boats they had worked on, we are called many names, but name-calling we are used to. Men thirst for women, even if they have to pay two dollars. But now that they can get it for free, now that they can get it and more, the big men tell us that we must leave by a certain day, that we must leave, and pretend that all these men were chaste and that nothing ever happened, that we are just a social evil…so we pack our small bundle, the bundle no bigger than the one we left home with. Money went to pay off debts, to drinks, to lovers, to clothes. To home. To all the things we thought important when we were paying for them: love. We carry our bundles and we disappear.

* * *

Black birds. White birds. Yellow birds. All the names for these women who dot the cities in California, in Oregon, in Seattle and Vancouver, Utah, Montana, Idaho. They were named for the men who bought their bodies. Black birds for women who serviced black men. White birds for white men. Yellow birds for those others, the Asian men, Japanese and Chinese. And these women are ranked accordingly, just as men see themselves: white men on top, black men second, and the Orientals at the bottom. Prices of women are also according to the color of the skin: hers. French women on top, other white women second, black women third, Chinese and Japanese women, and South American women on bottom. A white man may buy Japanese women in Butte, Montana, because that’s all he can afford, or because secretly, he fancies an Oriental girl – he can’t tell the difference between Japanese and the Celestials who came all the way from Shanghai or Hong Kong – but he dreams of the day when he can afford to call for a nice American girl from the East through the bride advertisement. But for now, as he toils his days in the mines or on the cattle ranch, he satisfies himself with a Nipponese girl for a cheap release.

0 comments