Learning from Twitter Trolls: A Feminist Survival Guide

By Meggie Mapes

Picture it: I was a budding social media feminist, learning the ropes tweet by tweet. By the end of the first day my hands were raw from the climb. From one perspective, it’s completely my fault. I had heard the rumors that they emerge from the depths of Internet misery to make your life hell every few seconds. I had heard of them, and yet, I arrogantly thought that I was immune to troll debauchery. It took but one feminist tweet to incite the trolling troops. Within moments, I was bombarded by Twitter trolls and buried in memes.

So, sure, maybe it was my fault. But on the other hand, no, it wasn’t. Let me backup.

I have been a feminist for, well, forever. Growing up with two brothers in an Iowa trailer, I commonly watched my single mom hustle while working two jobs and commuting four hours to graduate school. I grew up with a feminist mantra from my mother: Be independent, rely on yourself and always remember that marriage was born of men owning women. Divorced in her early 20’s, I witnessed my mother work viciously as a social worker in the school systems, barely making ends meat. Feminism was part of my bones; it was the sweet Iowa corn that strengthened my muscles. It’s more than an ideology that I walk in to and out of; feminism is a part of me—it always has been, and it always will be.

I have been a feminist for, well, forever. Growing up with two brothers in an Iowa trailer, I commonly watched my single mom hustle while working two jobs and commuting four hours to graduate school. I grew up with a feminist mantra from my mother: Be independent, rely on yourself and always remember that marriage was born of men owning women. Divorced in her early 20’s, I witnessed my mother work viciously as a social worker in the school systems, barely making ends meat. Feminism was part of my bones; it was the sweet Iowa corn that strengthened my muscles. It’s more than an ideology that I walk in to and out of; feminism is a part of me—it always has been, and it always will be.

Fast forward to the 2016 presidential primaries. I was, more than ever, with Hillary Clinton.

The role sexism played in coverage of her campaign was palpable. From the pantsuit jokes to the memes of her appearance, the only thing more obvious than the explicit sexism directed toward Hillary Clinton was the obliviousness that it was met with from both the Left and the Right. I couldn’t fathom the inability to admit that Hillary Clinton was clearly experiencing higher levels of scrutiny, supplemented by intense sexism and criticism over her appearance. I wasn’t asking people to believe everything she said or halt criticisms of a few questionable policy decisions. In fact, I regularly agreed with Joan Walsh who notes, “I continue to wonder whether [Hillary will] be more hawkish on foreign policy than is advised in these dangerous times. I’m concerned that she’s too close to Wall Street; I really wish she hadn’t given those six-figure talks to Goldman Sachs.” These criticisms are important because Hillary is not perfect, and I believe that criticisms—feminist and non-feminist—encourage Clinton to make better choices. However, I was also asking for acknowledgement that sexism was motivating so much of the cultural commentary surrounding Hillary Clinton.

A key component of my feminist writing is a commitment to online and public pedagogy, investigating common cultural norms and how they’re communicated on new media. So, with an ethic of dialogue in mind, I did what I do best: I began engaging online.

A key component of my feminist writing is a commitment to online and public pedagogy, investigating common cultural norms and how they’re communicated on new media. So, with an ethic of dialogue in mind, I did what I do best: I began engaging online.

Enter #BetterFirstWomanPresident, a trending hashtag that emerged days after Hillary was officially selected as the next Democratic nominee to be president of the United States.

Drinking my morning coffee, I began perusing the tweets, quickly glancing around my kitchen for something a little stronger. Yet again, Twitter had enabled hundreds of sexist and transphobic tweets about Hillary Clinton.

I was gutted. In a moment of monumental importance, a moment in which a woman—arguably the most qualified candidate in presidential history—may enter the oval office, tweeters created a hashtag that undergirds so much of patriarchal control: judging and pitting women against one another. The hashtag itself, #BetterFirstWomanPresident, explicitly asked Twitter personalities to judge Clinton against other women: who would be a better woman? Before any characters were entered, Clinton was measured and weighed, placed on scale of womanhood and found unfit.

And that was just the springboard needed for sexist Twitter trolls to expand. The more I read, the angrier I became. “How dare they create some disillusioned reality around what qualities the first woman president must possess,” my mind rattled. “We have no standards to judge a woman in the White House. We have no framework for a woman winning a presidential election. Why? Because it’s never happened before. WHY? SEXISM!”

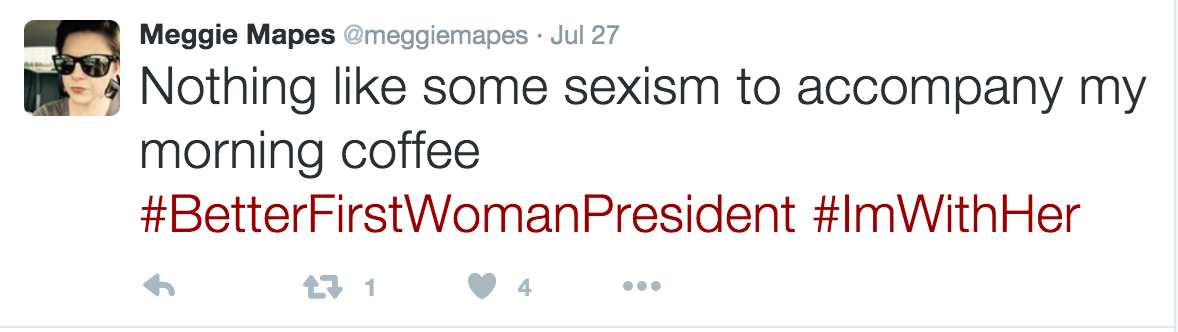

I couldn’t take it. In response to the feminist pit in my stomach, I typed a few short yet poignant letters. “Nothing like some sexism to accompany my morning coffee. #BetterFirstWomanPresident #ImWithHer.”

Unfortunately, those few letters are all it took. Within moments, I was engulfed in Twitter-troll-hell. I was told to “make me a sandwich,” over and over again. “Make me a sandwich” was accompanied by sexist memes of Hillary Clinton, old advertisements where women served men, and increased notifications that these engagements were re-tweeted. My attempts at engagement were frivolous; I was outnumbered. As hesitant as I was to admit it, being told to make men sandwiches in such an overtly sexist manner affected me. It did something to me. My graduate studies had shielded me into partially believing a long-held myth: women have come so far. I soon realized that Twitter trolls place feminists in an inherent double bind.

- A) You respond and, regardless of tone or reason, you’re labeled as “crazy,” “angry,” or “passive aggressive.” And, worse, they won’t stop. The more you engage, the more fuel trolls find to stereotype feminists, deny the existence of sexism, or resort to pure insult. Feminism as misandry is still a common trope of Twitter trolls who describe feminism as purely man-hating instead of a movement interested in intersectional social justice. My meager attempts to clarify and engage—including general inquiries into my comment—were met with increased hostility and sexist mockery. Every action justified a trolling response.

- B) You block them, a decision wherein trolls screenshot the block and post it as a “win” for them. And I did. I blocked them. Twitter tolls, unfortunately, must have some hereditary connection to white walkers, as every block led to more trolls emerging from the depths of Internet hell.

So, what are feminists who engage through social media supposed to do?

Sadly, I found little solace elsewhere. After sharing the experience with friends, they responded unsympathetically. “What did you expect? They’re trolls,” one said. “They don’t know you, and you don’t know them. I’m not surprised,” another noted. I felt horrible. I felt to blame. I felt like Twitter trolls had won. I felt like giving up. I felt like my intellectual expression as a woman had, yet again, been used as punishment. Worse yet? I am far from alone in experiencing the wrath of Twitter trolls. Searching for help, I found article after article of women articulating the cyberbullying they experienced online for their feminist commitments.

Sadly, I found little solace elsewhere. After sharing the experience with friends, they responded unsympathetically. “What did you expect? They’re trolls,” one said. “They don’t know you, and you don’t know them. I’m not surprised,” another noted. I felt horrible. I felt to blame. I felt like Twitter trolls had won. I felt like giving up. I felt like my intellectual expression as a woman had, yet again, been used as punishment. Worse yet? I am far from alone in experiencing the wrath of Twitter trolls. Searching for help, I found article after article of women articulating the cyberbullying they experienced online for their feminist commitments.

So, I ask again, what are feminists who engage online supposed to do?

- Get mad. Get bored. I was surprised at how emotionally exhausting my encounter with trolls became. Somehow I had convinced myself that I was insulated from anonymous sexism. In reality, I was desperately mad, frustrated by my inability to point to a “who”—a novelty eliminated by the anonymity of Twitter. I was also angry at myself for being so angry. Please, please let my emotional labor assist you to know the following: you have permission to be angry. You have permission to be hurt. When the anger subsides, and when you decide that you’ve had enough, get bored. Because it’s true, isn’t it? The sexism is boring. It’s predictable.

- Screen shot. Scrutinize. Script. The reason that trolls are partially successful is their lack of moral fiber. They will say anything; nothing is off limits. In response, most tweeters will minimize their interaction with trolls, deleting or ignoring the evidence. My feelings were hurt. Trolls hurt my feelings. Sue me. But it’s more than just pure emotional discomfort. My survival is partially dependent upon my ability to write. I screenshot interactions, place them in a desktop folder, and return days later to process what the heck went down. I suggest this tip, a bit selfishly, to encourage more men and women to publicize their experience with trolls, helping others know:

- Who to avoid.

- Who to lean toward.

- Support other feminists. I’ve expanded my Twitter process to include a general survey of common hashtags like #feminism and #BlackLivesMatter daily—locations where I find trolls breed and grow dramatically. By taking inventory, I am better equipped to support others who may fall prey to the troll trope, a pure denigration for an individual’s own enjoyment. Supporting one another is a long-time feminist commitment, and one commitment that, perhaps, needs more adaptation to online spaces.

- Block the bastards. Sometimes the “block” is the best bet. Protect yourself. Protect your time.

- Become a [clever] troll. This is a controversial suggestion, and one that I’ll premise with the following: my suggestion to “become” a troll is not a statement to support disparaging and “below the belt” comments. Rather, I advocate for more feminists to become savvy trolls, responding with common GIF’s, utilizing humor to correct blatantly sexist, racist tweets. By savvy, I mean responses grounded in a feminist ethic without using degrading language, resorting to straw person arguments and personal insults. I certainly don’t get it right every time, but being a feminist requires a constant interrogation of my interactions, reflecting and deciding just how “savvy” the engagements were, and always working to be better.

I would never describe this list as exhaustive. In many ways, trolls adapt too quickly, however, contemplating strategies are part of my own self-care. I wanted to quit being an online feminist activist. I wanted to walk away. But feminism isn’t about me, not completely; feminism is about my small efforts in a collective movement to end injustice. That small reminder is my realization that, despite trolls, I will continue the climb.

Meggie Mapes is a feminist writer and performer with a Ph.D. in communication studies. Committed to intersectional feminism, she studies the emergence of anti-feminist backlash in social media movements. She lives in Kansas City with her partner and two amazing dogs. Follow her on Twitter @MeggieMapes.

Meggie Mapes is a feminist writer and performer with a Ph.D. in communication studies. Committed to intersectional feminism, she studies the emergence of anti-feminist backlash in social media movements. She lives in Kansas City with her partner and two amazing dogs. Follow her on Twitter @MeggieMapes.

Pingback: Twitter Trolls as Social Advocates – DIGITAL COMMUSINGS