Waking Up to Rape Culture in Asheville

The first time I learned about rape culture was on the school bus. Soon after leaving the school parking lot, the boys in the row behind started in. “Have you gotten your period?” “Do you use tampons?” I could feel my face redden, my heart race, and my body stiffen. Instinctively I knew to stare ahead, to say nothing.

Where had I learned that responding to them would only make it worse?

The bus driver stopped where my neighborhood intersected the main road. I got off the bus, and one of the boys exited behind me. As the bus drove away, he pulled out a can of Easy Cheese. “Do you like this? Do you want some?” I didn’t and said so.

He came from the side and pushed me into a patch of grass into the nowhere land between the end of the road and the first house on the street. “Try it,” he demanded repeatedly, as he forced the aerosol can into my mouth. He tired out fast, but before getting off of me he looked me in the eye. “I’m gonna rape you with a tampon.”

I stood up, picked up my backpack, and began the quarter mile walk home. I was eleven.

I don’t remember if it took two hours or two days to say something, but I do remember the feelings in my body, even as I didn’t have the words to describe them then. I felt sick. I felt scared. I wished I could disappear. Eventually when the story came out, I told it quietly, hesitantly, as if in speaking the threat would come to pass.

I remember that my mom called the school. I remember that she talked to the school disciplinarian. I remember that I stopped riding the school bus. I remember that nothing happened. Not to him.

Two decades later, a colleague stopped me in the hallway on my way to the bathroom. “Can I read you something?” he asked. As college professors, we wrote, and we talked for a living. Listening to one another was part of the job. And yet, I dreaded what was coming next. His very presence had become a red flag. Over time, he expressed anger about his diminishing career with barely concealed threats.

His poem was called “Counter Rape” and if I had any doubt about whether the images of violently penetrating and ejaculating on the woman depicted were metaphorical, he clarified that he had a woman in mind, our boss. I remember the feelings in my body. The words are rage and fear. I remember that I told someone, several some ones. I remember talking to other women who’d also been on the receiving end of the poem. I remember that when we talked about it, we did so quietly, hesitantly, as if by talking we made ourselves increasingly vulnerable. And maybe we did. I also remember that nothing happened for a very long time, and so we kept walking the hallways, bracing ourselves for an attack.

These stories are, in and of, themselves unremarkable. Women and girls daily encounter subtle and obvious threats of sexual violence, bullying, and intimidation. Ask a woman if she’s experienced rape culture first hand, and she might say no. But ask her about the first time a boy said something to her that scared her, that made her want to disappear, and she’ll tell you a story.

Just this morning, a friend described a recent encounter with a drunk guy at a reservation counter in an airport. While she tried to rebook her flight, he leered. He murmured. He did all of the things that say, “I can do whatever the fuck I want, and no one is going to stop me.” And you know what, no one did. Not even as her children looked on.

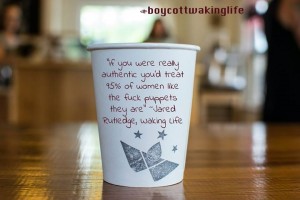

Image credit: http://ashvegas.com/opinion-the-asheville-communitys-response-to-waking-life-scandal-is-justified

Rape culture depends on not responding, and that is what makes recent events in Asheville, NC seem so remarkable.

On September 19, a local blog published a story about Jared Rutledge and Jacob Owens, owners of a local coffee shop, who when not serving coffee were alternately having sex with women and then blogging about it without their consent, tweeting about their theories of gender difference in vulgar terms, and podcasting about whether or not some of the sex they had was consensual. The story has exploded both locally and nationally and cracked open the online culture of so-called pick up artists, who share exploits and crowd source strategies to, in effect, dehumanize women.

Perhaps the saddest fact about this thing we call “rape culture” is that misogyny and violence are not uncommon. Rutledge and Owens were, after all, immersed in a vibrant online network. What makes the Waking Life scandal remarkable is the response.

Three things happened in Asheville:

First, the behavior was recognized as a kind of violence worth taking seriously. Asheville’s most outspoken social media voices immediately denounced the behavior as sexist and abhorrent. Second, the story was situated in a broader cultural context, as part of a systemic pattern of sexism and sexual violence. Initially, businesses that stocked Waking Life products began pulling their coffee from shelves. But one local business conceived the genius idea to sell the remaining products and to donate 1000% of sales to Our Voice, a local organization invested in dismantling rape culture. Third, folks mobilized immediately to extend resources to individuals impacted. A local food critic rallied his network to find jobs elsewhere for employees of the coffee shop.

Image credit: http://ashvegas.com/opinion-the-asheville-communitys-response-to-waking-life-scandal-is-justified

When the story broke, I, like so many, felt the rush of an accumulated rage. It was a reaction not simply to Rutledge and Owens’ actions but was also viscerally motivated by the cellular memory of that school bus ride, the rape poem, and actualized violence across my lifetime. At the same time, I felt astonished. What felt different is that there was a response to my rage and to the collective rage. Folks did what they could. Many spoke out. Others networked. Some raised funds. And in the time that’s passed, a conversation about rape culture has emerged, among survivors and the larger community.

Some things did not happen. By and large, women did not experience the burden of explaining why Rutledge and Owens’ behavior was wrong. Their tweets and podcasts weren’t dismissed as boys being boys. And survivors—both of the perpetrators’ direct violence and of their toxic work environment—were not left to fend for themselves.

What felt so odd over the last several weeks to me and to so many folks in this mountain town is that somebody did something. Lots of somebodies.

In rape culture, this level of response almost never happens. Often, there is no response at all.

Over the last several weeks, I have watched a community’s response with sheer amazement and some questions, too. Who has to be victimized and exploited before we respond? Why do we ignore women’s stories when there are no tweets and podcasts to point to? What does justice look like in this situation, and how does accumulated rage coalesce into a desire for revenge? How do our efforts to seek justice perpetuate violence? But most importantly, I wonder will there be a response next time and the time after that? And the time after that?

There is undoubtedly a pattern of silence in rape culture, and I’m not talking about women’s silence. There is a pattern of silence on the part of those who witness gendered violence–from schoolyard bullying to workplace harassment, from online threats to physical assault. A pattern of hearing but not listening, a pattern of seeing but not responding.

This very week, I received a desperate email from a friend seeking advice on behalf of another woman. This woman had recently reported a colleague’s startling behavior to her boss, patterns that could be described as stalking. Human Resources responded to her concerns, assuring her with words that are familiar to too many women. “He’s harmless.” What her higher ups failed to see is the harm that has already been perpetrated. In fact, her fear at finding him waiting by her car in the parking deck reveals a kind of harm. Her trepidation at opening her email is evidence, too.

The term “rape culture” has become a joke among anti-feminists and cultural conservatives, an attempt to mock women into remaining silent. Alluding to “rape culture” with an eye roll and a sneer is such an effective strategy of silencing women because it takes so much courage for women to speak up and name sexual violence at all. But rape culture isn’t upheld by the silence of victims. It’s fortified by a multitude of everyday silences—not intervening with a boy who uses rape to intimidate a girl, not challenging the bullying a woman experiences at work, not speaking up to the drunk guy at the airport. This month in Asheville, North Carolina, the silence broke.

Pingback: LINK: Waking Up to Rape Culture in Asheville by Heather Laine Talley | stuhelmfoodfan