A Review of Mecca Jamilah Sullivan’s Blue Talk and Love by Sarah Mantilla Griffin

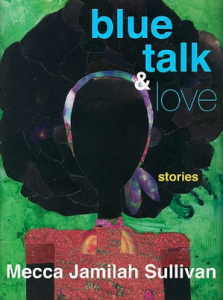

Review: Blue Talk and Love by Mecca Jamilah Sullivan

“A Block Party in Blue Mood”

by Sarah Mantilla Griffin

We have been waiting for a collection like this. In fourteen short stories, Mecca Jamilah Sullivan’s Blue Talk and Love transports readers from Harlem to Ethiopia and from the 19th century to the contemporary period; it includes the voices of an eight-year-old girl, of conjoined twin circus performers, and of a Chilean man, among others. Through these voices, Sullivan explores questions of difference and identity in their many forms, particularly through language and the body. Of foremost importance are the ways in which Sullivan’s protagonists take up space. Embodying sizes, shapes, and colors outside of society’s boundaries of the “normal,” Sullivan’s characters must make spaces for themselves in the world. Sullivan writes primarily of black girls and women who love words and use them in the creation and protection of their physical and psychical spaces. As in “A Magic of Bags,” Sullivan raises “bodily troublemaking [to] a practice, an art” such that the spaces her characters inhabit are not limited to their worlds, the page, or even the collection; Sullivan’s women take up space in the reader’s mind, long after the reading is through. We who, in the words of Audre Lorde, “have been forged in the crucibles of difference”—or, for that matter, have felt the strangeness of sameness—have been waiting for a collection that speaks so eloquently to that forging process. Together, the stories of Blue Talk and Love read as “a block party in blue mood,” an image borrowed from Sullivan’s Saleema. On this block, each house is a Lordian “house of difference,” such that Sullivan’s neighborhood offers the literary equivalent of the Harlem in her stories: a vibrant, messy, productive mix of differences and similarities held together by place and by the spaces they create.

Sullivan’s block party has distinctive rhythms, which are in step with current social movements, attitudes, and anxieties; the collection illuminates black lives and proclaims explicitly that they matter. These lives offer a grand meditation on intersectional identity—what it means and what it takes to accept and even love oneself as: a woman, a black woman, a queer black woman, a big queer black woman, or at the intersection of any other possible identifying category. The collection begins with “Wolfpack,” in which Sullivan makes clear that despite the beauty of her writing and her manifest love of language, Blue Talk and Love does not simply worship language. Instead, it interrogates both the power and limits of words, stretching the boundaries of what we have seen before. In large part through her exquisite mastery of simile, Sullivan offers sounds, sights, and, intriguingly, smells and tastes that literature has been missing. Providing these new and necessary impressions, Sullivan places herself as a unique voice within the contemporary scene while referencing her literary forebears. She offers us the unsettling realism of Gorilla, My Love, the Harlem coming-of-age of Zami, the reverie of Corregidora, the fantastic of Bailey’s Café, and the formal experimentation of Beloved. Using Georgia Douglas Johnson’s “Ivy” to structure her eponymous story, Sullivan gives the poem new life and meaning; it is hard not to feel this reverberation in one’s bones. The power of Sullivan’s words: “I am fragile…there are valleys here,” is in their simplicity, their truth, their importance, and their scarcity in the literary landscape.

Blue Talk and Love thinks and rethinks how girls and women are placed; how they are and are not deemed worthy of love, of vulnerability, of space, of care; how they are named and unnamed; and how these girls and women find—and lose—the words to label these experiences, to integrate them, and to imagine and instantiate selves and spaces for self. The stories are as diverse as are the characters within them; this range of identities is what gives the collection such vast intellectual reach. Sullivan’s Ph.D. in English Literature appears to have served as a complementary backdrop to her stories, helping to lay fertile philosophical ground without causing the collection to feel overly or self-consciously academic. Occasionally, Sullivan’s characters take on the beauty of her language within their voices. Although they are often engaged in processes of finding words for themselves, it can at times be difficult to believe that they are as gifted with words as Sullivan is; I have read few authors who are so remarkable. But complaining about a book’s language being too beautiful feels a lot like grousing about a dessert being too rich: one does not really mean it. Hence it is unsurprising that the dexterity, charisma, and knowledge with which Sullivan writes have earned her the Charles Johnson Fiction Award; honors from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Mellon Foundation, and the Center for Fiction in New York City; and inclusion in Callaloo, Best New Writing, and American Fiction, among many others.

Interrogating personhood, patriarchy, femininity, womanhood, sizeism, interpellation, representation, and more, Blue Talk and Love carves out space for itself and for Sullivan among the great works and writers of our time. Its last line punctuates the actualization of self performed not only by Sullivan’s characters, but by the book as a whole: “then I say my name.” Speaking itself into existence, Blue Talk and Love is a brilliantly ambitious, innovative entree into black women’s worlds and minds. It offers an intersectional blues for the contemporary moment, which sounds like “all that differentness” that makes us who we are. The collection lays bare Sullivan’s acceptance of Audre Lorde’s challenge “to reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives there. See whose face it wears.” It is a reckoning with that terror and loathing, a process through which self-love is possible. This is the triumph of women, which Blue Talk and Love celebrates such that, though the block party may be in blue mood, it is also filled with light and love and laughter and hope. We have been waiting for this party for quite some time now, and I am endlessly grateful that it has arrived.

~

Sarah Mantilla Griffin is a mother and a cultural critic. She holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Pennsylvania and a B.A. with honors in American Studies from Stanford University. Her research primarily focuses on African-American literature, with special interests in women’s writing, black feminist theory, and sound theory.

Sarah Mantilla Griffin is a mother and a cultural critic. She holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Pennsylvania and a B.A. with honors in American Studies from Stanford University. Her research primarily focuses on African-American literature, with special interests in women’s writing, black feminist theory, and sound theory.

0 comments