Toni Cade Bambara: A Woman of and for the People

By Guest Contributor on November 26, 2014By Michael Simmons

Toni Cade Bambara was an organizer who could write, and the sista could really write. But it is not as a writer that I knew Toni: although I first met her in the 1970s while she and Leah Wise were editing an issue of the Southern Exposure magazine. My essay “Up South” was featured in Leah and Toni’s co-edited issue. What struck me about Toni during this time was that she was continually engaged in forming organizations that allowed African American artists to develop and share their talent with the community. In doing this, Toni explicitly and implicitly redefined what it meant to be an artist. She eschewed attempts to make art a precious purview of self-conscious and self-centered folks.

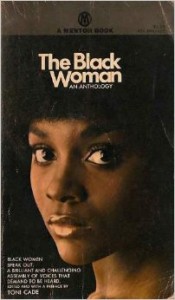

Even Toni’s seminal 1970 edited anthology, The Black Woman was as much an organizing document as it was a literary work. With contributions from novelist Alice Walker, poets Audre Lorde and Nikki Giovanni, writer Paule Marshall, activist Grace Lee Boggs, and musician Abbey Lincoln, among other bad sistas, “The Black Woman” introduced the world to sistas who would shape and redefine the image of the African American community and the world into the 21st century.

Even Toni’s seminal 1970 edited anthology, The Black Woman was as much an organizing document as it was a literary work. With contributions from novelist Alice Walker, poets Audre Lorde and Nikki Giovanni, writer Paule Marshall, activist Grace Lee Boggs, and musician Abbey Lincoln, among other bad sistas, “The Black Woman” introduced the world to sistas who would shape and redefine the image of the African American community and the world into the 21st century.

Toni also touched me in a very personal way because she became a mentor/an adopted spirit godmother to my daughter Aishah Shahidah Simmons. Despite the fact that Aishah and Toni’s daughter Karma shared a birthday party in 1975 and they both graduated from the Philadelphia High School for Girls in the same year, Aishah didn’t really “meet” Toni until the fall of 1989. Recognizing that Aishah was at a serious crossroads post surviving a rape during her sophomore year in college and subsequently leaving school, Toni invited Aishah to take her scriptwriting workshop for free at Scribe Video Center in Philadelphia. That invitation changed Aishah’s life. During Aishah’s early twenties, Toni provided her with a space to explore herself and her reality including coming out as a lesbian. She encouraged Aishah to dream her dreams without any concern for what obstacles she might encounter.

Moreover, Toni taught Aishah how to be an artist for the people. She shared with Aishah that art can and should be a gift to the dispossessed. Simultaneously, Toni also taught Aishah that art had value and that she should not allow institutions to devalue her art by not paying her. Aishah took this lesson to heart by ensuring all of the women who worked on her groundbreaking film, NO! The Rape Documentary were paid throughout the filmmaking process.

It was through Aishah that I really began to get to know Toni. I always used to tell Aishah that Toni was at another level of human evolution that few, if any, ever strive for, let alone reach. Although Toni had been part of the academy and was both an award-winning writer and filmmaker, she saw her “constituency” to be young Black girls, grown Black women, maids, nannies, hospital workers, homeless folks. Toni would bypass paid speaking engagements to engage folks in a homeless shelter. Toni understood that a woman who chose to sleep on the street rather than to be subjected to the indignities of a shelter was expressing an act of resistance and was not “crazy.”

In October 1994, Aishah, my son Tyree, and I were part of a small gathering of folks that heard Louis Massiah interview Toni at the James Hatch- Camille Billops Collection in New York City. As I listened to Toni talk about her childhood in Harlem in a way that made the “ordinary” sound magical, it moved me to revisit my own North Philly childhood. It was at that point that I realized my childhood had been more profound than I had ever considered. In particular, Toni’s discourse about her mother Mrs. Helen Cade Brehon (who was also in attendance that October afternoon) made me see my mother, Mrs. Rebecca White Simmons Chapman, in a completely new light, and to appreciate the multiplicity of her talents and the depth of her intellect. Until that point, probably like most people, I took her abilities for granted – she was just my mother. Inspired by Toni, I began to reflect on my mother’s life, in all of its facets.

Born in 1921, my mother left Rock Hill, South Carolina at age12 to make money to send back to her mother and nieces and nephews. She grew into an adult who always seemed to become a leader in any environment she was in. She was always willing to challenge authority – especially when it came to my brother Reginald and me, and our opportunities – and to take on authority, becoming a shop steward in her workplace. She nurtured my dreams by simply never assuming there was anything I couldn’t do. I didn’t even realize you had to pay for college because money never came up on that point. I just knew I would go. So when I finally learned you had to pay, money was never an obstacle in my mind. When I looked back on all of this, I finally recognized what an exceptional person my mother was. Toni’s living example helped me realize how easily we undervalue the ingenuity and creative capacity of “everyday” Black people. In that same vein, Toni rejected the notion of “mother wit” and “street smarts” to describe our mental proficiency and cheapen our intellectual contributions.

I learned about Toni’s death through the International Herald Tribune while in Budapest, Hungary, where I was leading an African American/Roma exchange. Among the African American participants were the late Faye Bellamy and Donald P. Stone and we all were shocked at the news. I immediately called Aishah knowing that she would be in a state of mourning. Toni was more than a professional mentor, more than a big sister-friend. She was a guiding force in Aishah’s life, and since Toni’s passing, Aishah has worked to keep Toni’s legacy and spirit present and alive.

As I reflect on Toni, perhaps what I respected most about her is that, though she had every right to do so, she never “cashed in”. With her literary and academic accomplishments Toni could have had an endowed chair and many emeritus titles but these things were never important to Toni. Her life ‘s mission was to use her art to uplift African American women, and by extension humanity. And that she did.

-Budapest,Hungary

Fall 2014

Michael Simmons has been an international human rights and peace activist over 45 years. Beginning as an organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee during the 1960s in the United States, over his career Michael has taken his work to Africa, Asia, Europe and the Middle East. He has organized conferences and seminars in Europe and Africa on the impact of East-West Tension on the Third World; seminars on peace and reconciliation in Bosnia, Macedonia and Kosovo during and after the Balkan War; a regional conference on sex trafficking in the Balkans; and has done extensive work with Roma in Central Europe on Roma human rights issues. He has lectured on and written about US foreign and military policy, nuclear weapons, conflict resolution, human rights, and all forms of violence against women, with an emphasis on trafficking of women and girls in the US, Africa and Europe. He regularly presents at international conferences and seminars, and frequently addresses workshops, symposia, classes, and student groups at universities in Europe and the United States. Michael is the Co-Director, with Linda Carranza, of the Raday Salon, a human rights program in Budapest, Hungary, focused on education and outreach. He also provides consulting services to non-governmental organizations, particularly those focused on human rights, anti-discrimination, and peace-building, and conducts trainings on human rights issues and advocacy for NGOs and youth activists. For more information, please visit: http://www.msimmons.org/

You may also like...

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

0 comments