By Laura Whitehorn

This might be a more sensational story if I wrote that I saw you for the first time standing tall and imperious, wrapped head-to-toe in African cloth as we met at JFK to board the flight for our trip to Vietnam. But you were all about the truth, and that wasn’t the first time I saw you.

We had been meeting for a few weeks, our little group of four women who the Vietnam Women’s Union had invited on a delegation to Hanoi during the final phase of what our hosts called the American War. When the invitation had come, the U.S. had yet to be seen scrambling onto helicopters fleeing Saigon, exiting in defeat. But by the time we actually left for the trip in July 1975, Vietnam was free of foreign invaders, though desperately tattered by the brutal years of warfare.

Our meetings—three white “anti-imperialist activist” women and you—had been dedicated less to getting acquainted than to learning about the country we were about to visit, reviewing etiquette and protocol so that we would act right. For me, it was also a dream: I was not only going to Vietnam, I would be there in the company of the imagination behind The Black Woman and Gorilla, My Love. I loved those two books that granted this middle-class white girl the privilege of hearing the unforgettable, enthralling voices in those essays and stories.

In those meetings, we discussed our first task: somehow, we were to smuggle around the world a large suitcase containing medicines our hosts had asked us to bring. We were breaking the U.S. embargo on material aid to Vietnam, defined by the U.S. as our “enemy.” You said you would handle it.

And you did. At JFK that day, you acted the part of African royalty, checking bags that were not to be inspected (still possible back then; imagine if we were doing this now).

The medicines survived every leg of the two-day trip unmolested. Arriving in Hanoi, we handed the luggage off to the delegation that met us at the airport. Near the end of our trip, we visited the Hospital for Women and Children in Hanoi, where we met women who had recently given birth. They and their babies were alive, we were told, thanks to the drugs we had brought: vials of injectable Valium to prevent convulsions during delivery—lethal convulsions caused, we learned, by exposure during pregnancy to the many defoliants with which the U.S. had blanketed Vietnam (still producing birth deformities and cancers these many years later, as I type this).

Traveling with you meant laughing a lot. I remember in particular one night in our hotel, after an intense day of meetings and discussions, when you had us all in hysterics with a long, colorful tale of attempted seduction involving frozen chrysanthemums floating in a bathtub and a dense, unresponsive professor date.

I also remember another story, less funny to me. It was about a community garden you had worked on in Georgia, and how some white, northern visitors had gushed over the “most delicious!!!” vegetables, when you knew they were just carrots, and the garden stood on its own without having to be a prize-winning culinary triumph. It didn’t need that bullshit.

The story was pointed. At dinner with a local Women’s Union branch earlier that evening, in my anxiety somehow to manage my senseless feelings of guilt as our hosts served us a feast—food cultivated from land and water bombarded by U.S. weapons while we, safe at home, had performed our paltry solidarity work against the war—I had asserted, “In the U.S., we can’t even eat fish like this, because our waters are so polluted by capitalism that the seafood is toxic.”

Rubbish, really, and you showed me so later, narrating the tale of similar idiocies from liberals visiting a Black southern community, romanticizing what they saw and in so doing, insulting the intelligence and discounting the creativity of the community they were visiting. Be honest, you said, without exactly saying it, solidarity can’t flower from bullshit.

Later, back home, meeting to sum up our trip, you had to convey that message in a stronger form. We were discussing how to convey the message: the people of Vietnam were grateful to anti-war Americans for our support during the war. Now they needed material aid for hospitals to treat those damaged by the war.

We had each taken photos for slide shows to use on fund-raising tours. We went through some of what we had seen—the Women’s Union chapters, community organizations, labor unions, clinics, schools. We faltered at schools. Our guides had told us there was a shortage of teachers for young students, because so many people had lost body parts to American bombs, land mines and the like. People with physical deformities were not allowed to teach young children, because the children would be frightened.

We should talk about that, about why policies are created and whether they are correct, and what kind of society they contribute to building, you said. The other three of us were aghast: nothing negative about the Vietnamese people should be conveyed, we said. It might reduce an audience’s willingness to contribute funds.

I don’t remember how the conversation ended; I’m sure we didn’t reach agreement. I’m certain I avoided the topic in the talks I gave, lacking the moral intelligence to talk about Vietnam without heroizing the people in an ultimately patronizing way.

You must have felt alone in our crowd, trying to get that message through to us. It took me awhile to get it.

When your book The Sea Birds Are Still Alive came out two years later, you sent me a copy. I loved that book of stories, and told you so, praising the excellence of many of the tales. You had to ask, Yes, but what did you think of the title story, the one about our trip? I mumbled something vague, but for real, I didn’t understand that story. Again, it conferred some unflattering attributes on some of the Vietnamese characters; it was not the single-mindedly heroic portrait my narrow ideology needed, of women planting rice then rushing fearlessly to shoot down American planes using outdated weapons. My vision did not countenance human frailty nor did it see, as you did, that the essence of heroism is being imperfect but acting anyway. And surviving as a people, not an image.

When your book The Sea Birds Are Still Alive came out two years later, you sent me a copy. I loved that book of stories, and told you so, praising the excellence of many of the tales. You had to ask, Yes, but what did you think of the title story, the one about our trip? I mumbled something vague, but for real, I didn’t understand that story. Again, it conferred some unflattering attributes on some of the Vietnamese characters; it was not the single-mindedly heroic portrait my narrow ideology needed, of women planting rice then rushing fearlessly to shoot down American planes using outdated weapons. My vision did not countenance human frailty nor did it see, as you did, that the essence of heroism is being imperfect but acting anyway. And surviving as a people, not an image.

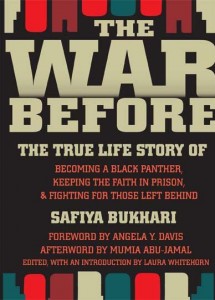

Thirty-two years later, I reread Sea Birds while editing a collection of writings by a Black Panther woman who, like you, had died much too young. It amazed me how clearly you had captured the extraordinary endurance of ordinary people and how much the story conveys about the nature of heroism, how collective it is. I named the book of Safiya Bukhari’s essays (which are about political prisoners from the Black liberation struggle) after a line from your story, where a woman sees some rusted weapons on a riverbank from the war with the French, the war before the one with the Americans. I called it The War Before and added the epigraph,

Thirty-two years later, I reread Sea Birds while editing a collection of writings by a Black Panther woman who, like you, had died much too young. It amazed me how clearly you had captured the extraordinary endurance of ordinary people and how much the story conveys about the nature of heroism, how collective it is. I named the book of Safiya Bukhari’s essays (which are about political prisoners from the Black liberation struggle) after a line from your story, where a woman sees some rusted weapons on a riverbank from the war with the French, the war before the one with the Americans. I called it The War Before and added the epigraph,

And that is why…the youth were so important, for they would prove to the ancestors that it had not been foolish to fight for the right to be free, to be human.

—Toni Cade Bambara, The Sea Birds Are Still Alive

I hope you would approve. I love you, but then you must know that, for this is a love note. No bullshit.

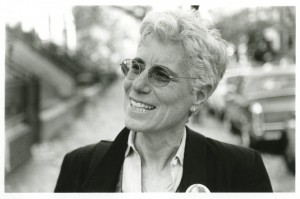

Laura Whitehorn spent 14 years in federal prison for the “Resistance Conspiracy Case.” Released in 1999, she lives in New York City with her partner, writer Susie Day. Since her release, Laura has been engaged in work to end prison injustice and free all political prisoners; she works on the project Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP). Laura edited The War Before: The True Life Story of Becoming a Black Panther, Keeping the Faith in Prison, & Fighting for Those Left Behind by the late Black Panther political prisoner and organizer Safiya Bukhari, and her writings have been included in books edited by Joy James, Johanna Fernandez, Mumia Abu-Jamal, and others. With a collective based out of Interference Archive in Brooklyn, she recently helped organize the exhibit “Self-Determination Inside/Out,” showing how the struggles of incarcerated people from the Attica rebellion to the present have affected social movements on the outside.

Laura Whitehorn spent 14 years in federal prison for the “Resistance Conspiracy Case.” Released in 1999, she lives in New York City with her partner, writer Susie Day. Since her release, Laura has been engaged in work to end prison injustice and free all political prisoners; she works on the project Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP). Laura edited The War Before: The True Life Story of Becoming a Black Panther, Keeping the Faith in Prison, & Fighting for Those Left Behind by the late Black Panther political prisoner and organizer Safiya Bukhari, and her writings have been included in books edited by Joy James, Johanna Fernandez, Mumia Abu-Jamal, and others. With a collective based out of Interference Archive in Brooklyn, she recently helped organize the exhibit “Self-Determination Inside/Out,” showing how the struggles of incarcerated people from the Attica rebellion to the present have affected social movements on the outside.

You may also like...

5 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire