I’ve Got Something To Say About This: A Survival Incantation

By Guest Contributor on November 21, 2014By Kate Rushin

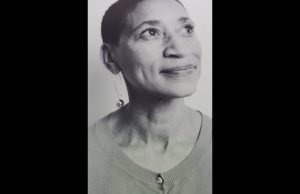

Remembering Toni Cade Bambara

I often think of an exchange I had with Toni Cade Bambara. I don’t remember the circumstance but I’ll never forget her response to my comment:

Something told me . . .

She looked at me and didn’t miss a beat:

Well, if something told you, why didn’t you listen?

Anyone who’s been in Toni Cade Bambara’s company can speak of her humor, her wit and her dazzling mind. “Huhm . . . Why didn’t I listen?”

I first read Toni Cade Bambara’s short stories in “Gorilla, My Love,” from a hardcover copy belonging to my English-teacher aunt, Mrs. Helen B. Morales who would take the bus from South Jersey to bookstores in Philly, because she could not abide paperbacks. I had learned about Toni Cade Bambara in the pages of Hoyt Fuller‘s “Negro Digest” (renamed Black World in 1969). My grandparents ran “Williams General Store” from the front of their house in the African American town of Lawnside, N.J. The “colored paper man” delivered the “colored papers:” The Pittsburgh Courior, The Philadelphia Tribune, The Baltimore Afro-American, and the Johnson Publications: Ebony, Jet and The Negro Digest. I would take one of the two copies of “The Negro Digest” that the delivery man left every month. I read about W.E.B. DuBois, Kwame Nkruma, and Langston Hughes. I learned about Black cartoonists, novelists and poets. I looked forward to their special issues on poetry, theater and fiction. One year I even cut photos of African American writers out of magazine for a school report.

I first read Toni Cade Bambara’s short stories in “Gorilla, My Love,” from a hardcover copy belonging to my English-teacher aunt, Mrs. Helen B. Morales who would take the bus from South Jersey to bookstores in Philly, because she could not abide paperbacks. I had learned about Toni Cade Bambara in the pages of Hoyt Fuller‘s “Negro Digest” (renamed Black World in 1969). My grandparents ran “Williams General Store” from the front of their house in the African American town of Lawnside, N.J. The “colored paper man” delivered the “colored papers:” The Pittsburgh Courior, The Philadelphia Tribune, The Baltimore Afro-American, and the Johnson Publications: Ebony, Jet and The Negro Digest. I would take one of the two copies of “The Negro Digest” that the delivery man left every month. I read about W.E.B. DuBois, Kwame Nkruma, and Langston Hughes. I learned about Black cartoonists, novelists and poets. I looked forward to their special issues on poetry, theater and fiction. One year I even cut photos of African American writers out of magazine for a school report.

When I got to college, I bought my paperback copy of Toni Cade Bambara’s ground breaking anthology, The Black Woman. It was first introduced to me by my African American Literature professor at Oberlin, Calvin C. Hernton.

I didn’t get to hear Toni in person until October of 1981. I was living in Boston and teaching as an Artist-In-Residence, at South Boston High School. I got into my used, tin-can Toyota and drove to her reading at Smith College. (That trip was also memorable because I met members of the Rushing branch of my family: the cousin and aunt I’d never met, Osula and her mother, Andrea Benton-Rushing, professor of Black Studies and English at Amherst College. I learned later that my aunt was the author of one of the articles in Black World that had been especially important to me, “Images of Black Women In Afro-American Poetry.”)

Thoughout the 1980’s, I heard Toni Cade Bambara give incisive talks and engaging readings. She was featured at The Celebration of Black Cinema V, with Clyde Taylor. He spoke at The Dark Room Collective on Inman Street in Cambridge. It was at the Dark Room where I first met Ayida Mthembu, a writer and counseling dean at MIT and a friend of Sister Toni. I heard Toni again at the Black Women Writers Reading Series pioneered by Marilyn Richardson at MIT. (I later taught the Black Women Writers class there, for several years.)

In 1994, the same week that the death of novelist and playwright Alice Childress had been announced on the radio, I once shared the bill with Toni Cade Bambara and Nikki Giovanni. Sister Toni sat backstage, before the reading, revising, by hand, a typed copy of a section from Those Bones Are Not My Child, a novel, she’d indicated, had taken her through changes to research and write. When I spoke in memory of Alice Childress, it was clear that Sister Toni had not known and was shocked by her passing.

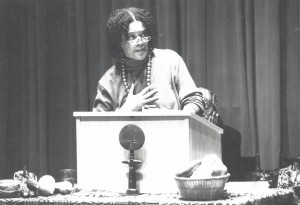

In the spring of 1995, when I served as Director of the Center for African American Studies at Wesleyan University, and we invited Toni Cade Bambara to deliver the CAAS Distinguished Lecture. I remember that someone in the audience asked her opinion about the public debate on between Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Molefi Kete Asante, that had been featured The Village Voice earlier that year. She informed the audience that the Academy was not her area of operation. Toni Cade Bambara was not going to get pulled into a debate she didn’t want to have in order to appear to be in-the-know; she wasn’t having it. It didn’t ‘t matter that the questioner insisted. She would not offer analysis or opinion. She was clear about her purpose, her mission.

After the reading, she asked what was going to happen next. I had assumed, because of her illness, that she’d want to be driven to back to her hotel to rest. Assume nothing. Sister Toni was direct: “That sounds boring!” It flashed across my mind that I didn’t know where to go for late-night jazz, or even an all-night diner in Hartford. I was new to the small-town that still closed down early on a weeknight and had allowed myself to get totally wrapped up on campus. And no one had thought to plan an after-event soiree. A small, impromptu group of us ended the evening in a manner that was nothing like the legendary 70’s and 80’s parties in the Amherst, Massachusetts, 5-College community, just an hour or so away, that I’d heard about; sets where James Baldwin or Nina Simone or a film-maker from a country in West Africa might walk in the door.

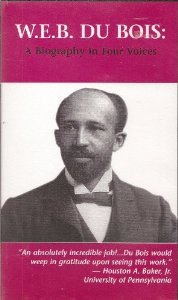

One of the most satisfying aspects of my time at Wesleyan was teaching Toni Cade Bambara’s work and introducing her to students. I screened the film W.E.B. DuBois: A Biography In Four Voices, (with Toni, Thulani Davis, Wesley Brown and Amiri Baraka) at the beginning of the semester in most of my classes, including poetry workshops. Directed and produced by Louis Massiah, Toni was the coordinating writer of the award-winning documentary film. I find the film to be especially helpful in providing a visual, political and historical context within which to place African American literature of the 20’s-80’s especially for non-majors. I can appreciate having the freedom to teach a course in the 1990’s called, Black Women Writers: Hansberry, Bambara and Lorde.” Each of these women had their own vision for social change; each left us too soon.

One of the most satisfying aspects of my time at Wesleyan was teaching Toni Cade Bambara’s work and introducing her to students. I screened the film W.E.B. DuBois: A Biography In Four Voices, (with Toni, Thulani Davis, Wesley Brown and Amiri Baraka) at the beginning of the semester in most of my classes, including poetry workshops. Directed and produced by Louis Massiah, Toni was the coordinating writer of the award-winning documentary film. I find the film to be especially helpful in providing a visual, political and historical context within which to place African American literature of the 20’s-80’s especially for non-majors. I can appreciate having the freedom to teach a course in the 1990’s called, Black Women Writers: Hansberry, Bambara and Lorde.” Each of these women had their own vision for social change; each left us too soon.

The Last Time I Saw Sister Toni

Ayida invited me to go down to Philly to visit Sister Toni in the summer of 1995. I consider it a gift that Toni Cade Bambara welcomed me into her home at a time when she was battling a serious illness, and I don’t know what else. She welcomed me in at a time when the circumstances in her life were less than “perfect,” “righteous,” or “fierce.” I don’t think I could do that; maybe that’s something (courage? priorities?) I need to work on. I remember reading the numerous plaques and awards from countless organizations that were stacked and propped around the apartment and thinking, “all good, but illness, cancer, is something else, again.”

It was a beautiful Saturday in Mt. Airy. There happened to be a community festival on Germantown Avenue. It was the sort of happening that might have been the model for a scene from The Salt Eaters, complete with young and grown African American men drumming, women promenading across cobblestoned streets, kids running and laughing and riding bikes, vendors selling incense, jewelry and brightly-colored dresses and scarves, sketch artists; elders sitting in lawn chairs, in the shade. The three of us, Ayida, Sister Toni and I got “fishammiches” (fried fish sandwiches) and strolled up and down, underneath the lovely buttonwood trees. . .Later that evening, we went down to Penn’s Landing with it’s throngs of people, on the waterfront, with a view of the Ben Franklin Bridge. We sat on the stone steps of the amphitheater to talk and people-watch. Sister Toni pulled a deck of cards out of her bag and regaled us with Black Jack strategy and broke down the concept of “double-down.”

There was a terrible snow storm in the Northeast the December weekend that Toni Cade Bambara passed, later that year. Ayida was taking the train from Boston to Philly to visit Sister Toni, who, by that time was in hospice. I was dealing with the end-of-the-semester responsibilities and was (for reasons that seem incomprehensible to me now) preparing myself to squeeze major surgery and recovery into winter break. I knew if I didn’t drive to New Haven and meet Ayida on the Amtrak Northeast Corridor train, I would likely not see Sister Toni again. I also knew that I had to take care of myself, buffer my energy and my psyche. I knew that she would understand. Ayida reported that the hospice staff was very kind and loving; that Toni was well-cared for and that when she was told that I sent greetings, she spoke my name and smiled.

Coda: “I’ve Got Something to Say About This: A Survival Incantation”

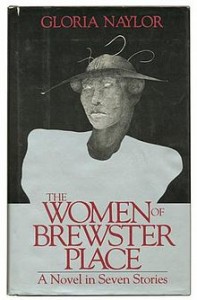

In Richard Wright‘s classic novel, Native Son, Bigger Thomas murders the daughter of his employer and, in his fear and desperation to avoid capture, smashes the skull of his girlfriend, Bessie, with a brick, as she sleeps, then throws her body down an air shaft. Wright does not give Bessie any words during the last moments of her life: “There was a dull gasp of surprise, then a moan.” In Gloria Naylor‘s award-winning novel, The Women of Brewster Place, Lorraine, the girlfriend of Theresa, is gang-raped by 6 young men from the neighborhood, and, in fear and trauma, kills her only friend in the neighborhood, an elderly man. Her only words after the attack are: “Please. Please.”

In Richard Wright‘s classic novel, Native Son, Bigger Thomas murders the daughter of his employer and, in his fear and desperation to avoid capture, smashes the skull of his girlfriend, Bessie, with a brick, as she sleeps, then throws her body down an air shaft. Wright does not give Bessie any words during the last moments of her life: “There was a dull gasp of surprise, then a moan.” In Gloria Naylor‘s award-winning novel, The Women of Brewster Place, Lorraine, the girlfriend of Theresa, is gang-raped by 6 young men from the neighborhood, and, in fear and trauma, kills her only friend in the neighborhood, an elderly man. Her only words after the attack are: “Please. Please.”

From the first time I read these novels, I was troubled by these particular characterizations. I was especially troubled that these characters are Black women who do not, cannot, articulate their own experiences. The nature of my dis-ease was crystallized in my mind, when I read the words of Toni Cade Bambara, writing about her perspective on “The Organizer’s Wife,” in the essay, “What I Think It Is I’m Doing Anyway.”

. . .I am well aware that we are under siege, that the system kills, . . .But death is not a truth that inspires, that pumps up the heart, that mobilizes . . .

‘The Organizer’s Wife,’ . . . is a love story, layer after layer. Lovers and combatants are not defeated. That is the message of this story, the theme of the entire collection, the wisdom that gets me up in the morning, honored to be here. That is a usable truth.[1]

I wrote this persona poem in the voice of a woman who thinks, speaks, and acts on her own behalf.

I wrote this poem as encouragement, to give heart to myself and to others.

I’ve Got Something To Say About This: A Survival Incantation

+++++++++I am well aware we are under siege . . . But death is not a truth that inspires.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++Toni Cade Bambara

I see it in your eyes.

+++++++++++++++++++++I see the whole thing played out.

+++++++++++++++++++++I’m bludgeoned, bloody, raped.

+++++++++++++++++++++My story is reduced to filler

+++++++++++++++++++++buried in the back of the paper,

+++++++++++++++++++++on page 49, and I say, “No. No way.”

This is it . . .Think.

Remember.

Now.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++Later for confusion and “This can’t be real.”

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++Later for regrets and “Why me?”

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++Later for guilt and “What if?”

+++++++++++++++++++++Now I can see headlines;

+++++++++++++++++++++now I’m the one on trial.

+++++++++++++++++++++But that’s alright, that’s really alright.

If only one of us can live

through this, I’m the one.

+++++++++++++++++++++I remember everything.

+++++++++++++++++++++In 7th-grade glee club, Miz Jay said:

+++++++++++++++++++++“Open your mouth wide, Girl.

+++++++++++++++++++++You can’t look cute and sing.”

I open my mouth wide.

I can’t look cute and live.

+++Crazy? Hell yesh, I’m crazy.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++You haven’t seen crazy

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++’til you’ve see me

+++saving my own life.

+++++++++++++++++++++I remember everything.

+++++++++++++++++++++In self-defense class, Big Ed told us:

+++++++++++++++++++++“They think you stupid. An eyeball is

+++++++++++++++++++++just an eyeball, knees give out,

+++++++++++++++++++++eardrums are not made of steel.”

You think I’m stupid

but I’m standing here thinking.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++Later for the pain.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++Later for the healing.

Later for you, Jack.

+++++++++++++++++++++My mind is made up for me.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++I am living, now.

I am sinking my teeth into

anything I can and I’m

spittin’ it back on you.

+++++++++++++++++++++Backonya . . .

+++++++++++++++++++++Backonya . . .

+++++++++++++++++++++Backonya . . .

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++I am doing what I need to do, now.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++I’ve got something to say about this.

I am

living.

Now.

© 2014

Editors’ Note: A different version of this poem appeared in The Black Back-Ups.

[1] Bambara, Toni Cade “What It Is I Think I’m Doing, Anyway,” in The Writer and Her Work, Janet Sternburg, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2000, 1980.

Kate Rushin is the author of The Black Back-Ups, “The Bridge Poem,” which was first published in the ground breaking anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Radical Writings by Women of Color and she was a member of the New Words Collective for ten years. She received an MFA in Creative Writing from Brown University and has taught poetry writing workshops and African American Literature courses at MIT, UMASS-Boston, Wesleyan University. Kate has received fellowships from The Massachusetts Artist foundation, The Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown and the Cave Canem Foundation. Her work appears in Callaloo, Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes and Black Women in America by Melissa-Harris Perry and Sunken Garden Poetry (Wesleyan University Press). She has been featured at the Sunken Garden Poetry Festival and on National Public Radio. Kate serves on The Connecticut Poetry Circuit and The James Merrill House Committee. She has held residencies at AS220 in Providence, RI and at Westfield State University in Massachusetts and has run Poetry Out Loud workshops for the CT Humanities Foundation.

You may also like...

1 Comment

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire