Feminists We Love: Toni Cade Bambara

By Heidi R. Lewis on November 21, 2014Editors’ Note: Since this is a special forum celebrating the life, work, and legacy of Toni Cade Bambara, one of our ancestor heroines, TFW made the editorial decision to republish Heidi R. Lewis’ “Feminists We Love: Toni Cade Bambara,” originally published during a one-day mini-forum on March 25, 2014, which would have been Toni Cade Bambara’s 75th birthday.

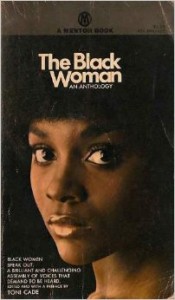

The Black Woman: An Anthology. One of the most important gifts I’ve ever been given. And I’m sure she knew she was giving it to me, along with so many other Black women, eleven years before I was even born. Toni Cade Bambara gave me Kay Lindsey, Abbey Lincoln, Gail Stokes, Frances Beale, herself, and so many other women that I may never have known had I never picked up that little black book.

The Black Woman: An Anthology. One of the most important gifts I’ve ever been given. And I’m sure she knew she was giving it to me, along with so many other Black women, eleven years before I was even born. Toni Cade Bambara gave me Kay Lindsey, Abbey Lincoln, Gail Stokes, Frances Beale, herself, and so many other women that I may never have known had I never picked up that little black book.

For every time I was pushed into deafening and paralyzing heteropatriarchal politics—before I even knew those words existed—Lindsey wrote, “But now that the revolution needs numbers/ Motherhood got a new position/ Five steps behind manhood/ And I thought sittin’ in the back of the bus/ Went out with Martin Luther King.” For every time I was abandoned and left alone to hold my community on my back—before I was even old enough to ride a bike without training wheels—Lincoln wrote, “Play hide and seek as long as you can and will, but your every rejection and abandonment of us is only a sorry testament of how thoroughly and carefully you have been blinded and brainwashed.” For every time I felt obligated to dim my light so that a Black man may shine in the darkness of white supremacy, Stokes wrote, “I eagerly and happily feed you from the plate of motivation knowing that it is difficult for you to help yourself. But, then at times you cause my arms to grow weary as I work harder straining myself in order to build you up. Straining myself as I watch you now and again hesitate and then refuse the nourishment.” For every time that I wondered why there was a gaping theoretical holes where I knew Black women should be, Beale wrote, “We as Black women have got to deal with the problems that the Black masses deal with, for our problems in reality are one and the same.”

And for every time I couldn’t sit still or remain silent and for every time I felt compelled to move outside of “my place,” to say and do “too much,” Toni Cade Bambara wrote,

The daughter, heretofore relegated to a mute existence as a minor in her father’s household or a minor in her husband’s household, found through involvement with the struggle a new discipline, a world of responsibility. She was no longer simply an item in a marriage contract or business deal but a revolutionary committed to action.

Toni Cade Bambara gave me a feminism that was Black—a feminism that was loud, strong, collective, vulnerable, powerful, communal, honest, and intimate, a feminism that was me, and that would be waiting for me, whenever I was ready.

She gave me the kind of Black feminism that wasn’t afraid to look around and that refused to suffer fools, declaring, “I try to live [the Golden Rule] and I certainly expect it of some particular others. But I’ll be damned if I want most folks out there to do unto me what they do unto themselves.” At the same time, she was equally invested in the kind of self-reflexive work that soothes as much as it stings. Her work continually asks us, like healer Minnie Ransom asks Velma in The Salt Eaters,

Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well? Just so’s you’re sure, sweetheart, and ready to be healed, cause wholeness is no trifling matter. A lot of weight when you’re well.” The feminism she gave me is heavy—obliging me both epistemologically and ontologically. For these reasons, I often still wonder if I’m really ready, for, as she once said, “revolution begins with the self, in the self.

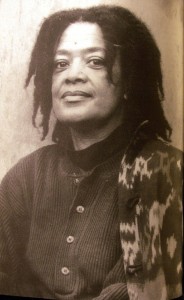

Toni Cade Bambara was born Miltona Mirkin Cade on March 25, 1939 to Walter and Helen Cade in New York City. 30 years later, she added Bambara to her name to honor the West African Mandé community. After graduating from Queens College with a Bachelor’s degree in Theater and English Literature, she studied at the Ecole de Mime Etienne Decroux in Paris. Later, she earned a Master’s in American Studies at City College in New York, while serving as Program Director of the Colony Settlement House in Brooklyn, NY. She also worked in social services, and was a Recreation Director at Metropolitan Hospital. In the mid-1960s, she worked for City College’s Search for Education, Elevation, Knowledge program and with SEEK’s theater. She returned to the academy to become an Assistant Professor of English at Livingston College and also a Visiting Professor of Afro-American Studies at Emory and African American Studies and Social Work at Atlanta University. She was also a Writer-in-Residence at the Neighborhood Arts Center, Stephens College, and Spelman, and she taught Film and Script Writing at Louis Massiah’s Scribe Video Center.

Toni Cade Bambara was born Miltona Mirkin Cade on March 25, 1939 to Walter and Helen Cade in New York City. 30 years later, she added Bambara to her name to honor the West African Mandé community. After graduating from Queens College with a Bachelor’s degree in Theater and English Literature, she studied at the Ecole de Mime Etienne Decroux in Paris. Later, she earned a Master’s in American Studies at City College in New York, while serving as Program Director of the Colony Settlement House in Brooklyn, NY. She also worked in social services, and was a Recreation Director at Metropolitan Hospital. In the mid-1960s, she worked for City College’s Search for Education, Elevation, Knowledge program and with SEEK’s theater. She returned to the academy to become an Assistant Professor of English at Livingston College and also a Visiting Professor of Afro-American Studies at Emory and African American Studies and Social Work at Atlanta University. She was also a Writer-in-Residence at the Neighborhood Arts Center, Stephens College, and Spelman, and she taught Film and Script Writing at Louis Massiah’s Scribe Video Center.

Toni Cade Bambara was also an accomplished writer, publishing The Black Woman: An Anthology (1970), Tales and Stories for Black Folks (1971), Gorilla, My Love (1972), The War of the Wall (1976), The Sea Birds Are Still Alive: Collected Short Stories (1977), The Salt Eaters (1980), Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions: Fiction, Essays and Conversations with Toni Morrison (1996), and Those Bones Are not My Child (1999), among other texts. A founding member of the Southern Collective of African-American writers, she was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame 20 years after her death in 1995. She also produced numerous screenplays, including Zora (1971), The Johnson Girls (1972), The Long Night (1981), Tar Baby (1984), The Bombing of Osage Avenue (1986), and others. In addition to teaching, writing, and producing, her transnational activism during the Civil Rights and Black Power movements led her to both Cuba and Vietnam.

This year, she would have been 75 years old. And while her physical body is no longer with us, we honor her spirit, her life, her words, and her work, because Toni Cade Bambara—activist, author, documentary filmmaker, professor, daughter, sister, and mother—is undoubtedly a feminist we love.

Heidi R. Lewis is an Assistant Professor of Feminist & Gender Studies at Colorado College. Her teaching and research focus on feminist theory, gender and sexuality, Black Studies, Critical Media Studies, Critical Race Theory, Critical Whiteness Studies, social justice, and activism. Her essay “An Examination of the Kanye West’s Higher Education Trilogy” is featured in The Cultural Impact of Kanye West, and her article “Let Me Just Taste You: Li’l Wayne and Rap’s Politics of Cunnlingus” is forthcoming in the Journal of Popular Culture. She is currently in the process of completing articles that examine Rihanna’s “Pour It Up,” as well as FX’s The Shield. She is also the Co-Curator and Co-Editor, with Aishah Shahidah Simmons, of The Feminist Wire’s “Toni Cade Bambara 75th Birthday Anniversary Forum.” She has given talks at Kim Bevill’s Gender and the Brain Conference, the Frauenkreise Projekt in Berlin, the Educating Children of Color Summit, the Sankofa Lecture Series, the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement, the Gender and Media Spring Convocation at Ohio University, and the Conference for Pre-Tenure Women at Purdue University, where she earned a Ph.D. in American Studies (2011) and a Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies (2008). Heidi has also been a contributor to Mark Anthony Neal’s NewBlackMan, NPR’s “Here and Now,” KOAA news in Colorado Springs, and KRCC radio (the Southeastern Colorado NPR affiliate), and she was featured as a Racialicious “Crush of the Week.” She and her husband, Antonio, live in Colorado Springs with their two children, AJ and Chase, and their cat Max. Learn more by following Heidi on Twitter at @therealphdmommy and by visiting her FemGeniuses website.

Heidi R. Lewis is an Assistant Professor of Feminist & Gender Studies at Colorado College. Her teaching and research focus on feminist theory, gender and sexuality, Black Studies, Critical Media Studies, Critical Race Theory, Critical Whiteness Studies, social justice, and activism. Her essay “An Examination of the Kanye West’s Higher Education Trilogy” is featured in The Cultural Impact of Kanye West, and her article “Let Me Just Taste You: Li’l Wayne and Rap’s Politics of Cunnlingus” is forthcoming in the Journal of Popular Culture. She is currently in the process of completing articles that examine Rihanna’s “Pour It Up,” as well as FX’s The Shield. She is also the Co-Curator and Co-Editor, with Aishah Shahidah Simmons, of The Feminist Wire’s “Toni Cade Bambara 75th Birthday Anniversary Forum.” She has given talks at Kim Bevill’s Gender and the Brain Conference, the Frauenkreise Projekt in Berlin, the Educating Children of Color Summit, the Sankofa Lecture Series, the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement, the Gender and Media Spring Convocation at Ohio University, and the Conference for Pre-Tenure Women at Purdue University, where she earned a Ph.D. in American Studies (2011) and a Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies (2008). Heidi has also been a contributor to Mark Anthony Neal’s NewBlackMan, NPR’s “Here and Now,” KOAA news in Colorado Springs, and KRCC radio (the Southeastern Colorado NPR affiliate), and she was featured as a Racialicious “Crush of the Week.” She and her husband, Antonio, live in Colorado Springs with their two children, AJ and Chase, and their cat Max. Learn more by following Heidi on Twitter at @therealphdmommy and by visiting her FemGeniuses website.

You may also like...

3 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Statement on Ferguson | FemGeniuses

Pingback: Feminists We Love: Linda Janet Holmes [VIDEO] - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire