Hands Up, Don’t Shoot: Black Self-Defense in the Wake of Ferguson

By Luam Kidane and Hakima Abbas

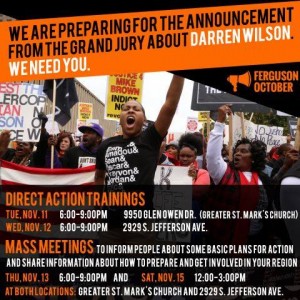

After nearly three months of deliberation the grand jury decision on whether to indict the police officer who murdered Mike Brown is expected to be announced next week. With press coverage intensifying and the government announcing that over 1000 police officers have received 5000 hours of training to “…deal with potential unrest…” we must seriously reflect on the state of Black self-defense and our holistic readiness to defend our communities in the face of increasingly militarized offensives from the state, its agents and vigilantes.

Hands Up, Don’t Shoot

The sight of Black people facing police guns and tear gas with their hands raised is as apt as it is painful. The intention is to highlight our ‘innocence’ in the face of systematic state violence and to be in solidarity with Mike Brown who was shot six times by a police officer while his hands were raised in surrender. This gesture reinforces the powerlessness of our community to respond to the sustained onslaught of police violence on, primarily, our young people, but systematically, us all. This stance of surrender may indeed be reflective of the state of our self-defense.

The sight of Black people facing police guns and tear gas with their hands raised is as apt as it is painful. The intention is to highlight our ‘innocence’ in the face of systematic state violence and to be in solidarity with Mike Brown who was shot six times by a police officer while his hands were raised in surrender. This gesture reinforces the powerlessness of our community to respond to the sustained onslaught of police violence on, primarily, our young people, but systematically, us all. This stance of surrender may indeed be reflective of the state of our self-defense.

And yet, when Mike Brown was murdered on August 9th in Ferguson, Missouri, his family and community reacted instantly, taking to the streets, to social media, to the media and to each other, to act against the system that murdered Mike Brown and that murders countless other Black people globally. Spurred by both the egregious circumstances of Mike Brown’s murder as well as the growing resistance in Black communities across the U.S. due to the murder of a Black person every 28 hours, the Ferguson community insisted that the world pay attention. Despite their protests and cries for justice being met with the full force of militarized police, the community of Ferguson continued to take to the streets, inspiring other Black communities to organize local actions or to join the demonstrations in Ferguson demanding justice for Mike Brown.

Soon, community organizers, both from Ferguson and outside of Ferguson, began to hold town halls to discuss community safety and how to protect each other as the militarized repression against the protests intensified. It was during this phase of the ongoing uprising that the hands up, don’t shoot symbol began to be used during confrontations with the police. This gesture quickly became the most dominant symbol of the Ferguson protests with Black and non-Black people around the world replicating this stance in solidarity.

Symbols of Solidarity and Resistance

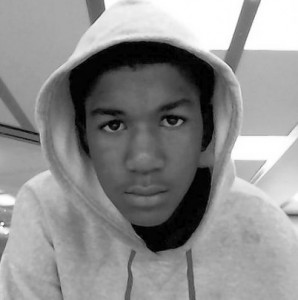

The impact of solidarity is heavily influenced by the symbols we utilize for mobilization. This is particularly true in the age of digital media where hashtags, protest slogans, and memes can be shared within seconds. When seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin was murdered by an armed white adult claiming self-defense because Trayvon was wearing a hoodie and carrying skittles, social media went viral with ‘hoodies for Trayvon’ as a call to action. The imagery challenged the notion of Black people and a perceived Black aesthetic, the hoodie, as threatening. As the campaign demanding justice for Trayvon grew, non-Black people also began to use the hoodie as a symbol of solidarity, rendering the imagery obsolete: because we are not all Trayvon Martin. The aesthetic and symbolism of solidarity is complicated by the messenger. In the case of Trayvon Martin the hoodie symbolized the systemic and direct physical violence perpetrated on Black bodies as a result of the centuries-old white propaganda of Black, and young, and poor, as threatening. However, once it was transposed into the mainstream and carried by non-Black people, this symbol no longer told a story of systemic violence on Black bodies but isolated this to the tragic case of a murder of a Black child. Important as the latter is, the isolation of the case puts blame and accountability solely on the ‘guilty’ individual and not on the system, in turn allowing those who show solidarity through the gesture of wearing a hoodie to remove themselves from culpability.

Hands Up, Don’t Shoot as a symbol of solidarity and as a point of action is an intriguing permutation. It melds the digital age of social media activism, characterized in part with short, catchy phrases that are easily ‘hash-tagged’, with the familiar moral pleas persistent in one stream of Black struggle movements. Hands Up, Don’t shoot reinforces that being in any position other than surrender opens up the debate of whether the killing of a Black person by the state was ‘justified’, leaving the question of whether Mike Brown had the right to resist outside of the parameters of the protests demanding justice. Would his death have been less of a rallying call if he were fighting back against a system, premised on the genocide of Indigenous peoples and the enslavement of Africans, that was already trying to kill him before it shot him down? #IfTheyGunnedMeDown followed a similar trajectory in that its central grievance was that Mike Brown was going to college but was being portrayed in the media as a thug. The plea is based on the formulation of innocence and respectability. However, the problem is that, by virtue of being Black, we are already guilty in the eyes of the system. This is why Trayvon Martin’s murderer is alive and profiting from his murder, and why Mike Brown’s murderer is still at large, despite having been identified and named.

Despite the tenacity of the Hands Up symbol, resistance in Ferguson has gone beyond moral plea organizing and moved with militancy, vision, and actions informed by a stance that refuses to negotiate the worth of all Black lives and that builds Black community. Throughout the history of occupation, genocide and crimes against humanity targeting African peoples: “The only place where Negroes did not revolt is in the pages of capitalist historians.” Ferguson is no exception. Despite, the hands up, don’t shoot symbol, the people of Ferguson are doing everything but surrendering and instead they are coming together in self-defense with Black communities throughout the country.

Black Self-Defense Reimagined

In 1965, El Hajj Malik El Shabazz, also known as Malcolm X, famously said, “We declare our right on this earth to be a man, to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.” The last three words captured the attention of a generation and of generations to come. ‘By any means necessary’ became the rallying call for direct action and armed resistance for the advancement of Black liberation struggles. But Malcolm was not the first, nor the last, to rally African peoples around notions of self-defense. African people globally have created theory and practice on the same. Examples include Queen Mother Moore, Frantz Fanon, Harriet Tubman and Robert F Williams. Self-defense and armed resistance have saved Black lives and communities.

From coastal uprisings of kidnapped Africans to organized revolts in forced labor camps, Africans have deployed multiple tactics of resistance and formulated strategies that understand armed resistance to be a part, but not the only component of self-defense. While the dominant understanding and propagated image of Black self-defense in popular culture and narrow nationalist organizing is limited to militarized displays of male-centered force, it remains clear that the holistic protection of Black bodies and communities, which include physical safety, the right to equitable resource access, and to self-determine cannot co-exist with white supremacy, capitalism and patriarchy. Taking instruction from Black histories of resistance, it is essential that our understanding of ‘any means necessary’ include ‘all means necessary’ or ‘every means necessary’. Our self-defense must include working to defend all African bodies, including but not limited to crip, queer, trans, cis-men and women, young, and old — from physical violence as well as defense from other manifestations of violence, including the psychological warfare of oppression, the violence of impoverishment and the deliberate marginalization of Black communities to access healthy food and holistic health care. The day after the verdict will be one part of this, no matter what that verdict is, but we can’t stop there.

Ferguson has been a spark in a long history of struggle. Black people all over the world are demanding justice for all African communities. Organizing that is not only mobilized in reaction but that exists continually to build power is imperative to our sustained struggles. We need to reignite our imaginations of a Black militancy that believes our resistances can transform our lives outside of the bounds of oppressions as they manifest outside and within our selves, our communities and our movements. It is not enough to focus our energies on dismantling the systems of oppression, we must concurrently build ways of life rooted in freedom. As Assata Shakur says: “We must be weapons of mass construction.”

Some of the most powerful images and stories out of Ferguson have been those of Black people protecting each other and protecting their communities. Standing in front of police throwing back teargas canisters in rage and resistance, the people of Ferguson have been an inspiration and a reminder of the fire Black liberation movements hold. Community members who have made food, shared knowledge and tactics on safety, created holistic healing spaces and facilitated spaces for community to strategize and build, are supporting the movement to be able to sustain ongoing front-line confrontations as well as to develop violence prevention mechanisms, create frameworks for justice and healing, as well as build alternatives to policing and self-determined institutions. Moments of collective action like those happening in Ferguson are important lessons for how movement building can defend Black lives by every means necessary.

—————————

Luam Kidane is a queer African inter-disciplinary educator, facilitator, and writer. Luam’s research, writing and work examines contemporary African movement building at the intersections of decolonial aesthetics, Indigenous governance models, art, articulations of self-determination, and media. Follow her @luamkidane.

Luam Kidane is a queer African inter-disciplinary educator, facilitator, and writer. Luam’s research, writing and work examines contemporary African movement building at the intersections of decolonial aesthetics, Indigenous governance models, art, articulations of self-determination, and media. Follow her @luamkidane.

Hakima Abbas is a political scientist and activist and a member of The Feminist Wire collective. You can follower her on twitter at @HakimaAbbas.

1 Comment