Touching Base with Tayari Jones: An Interview on Black Female Writers and Readers

By Eve Dunbar

Tayari Jones attended a brunch in Brooklyn to which I was also invited a few weeks ago. Seven-deep in the a living room of our mutual friend, Tricia, the brunch party flitted from considering who among us would fight if threatened with being ”jumped“ by one of our students after class to the best pedagogical approach to the “N-Word” within the racially mixed classrooms that many of us teach. In the midst of all this fun and food, Tayari often provided the perfect Toni Morrison quote or a textual example from some other black female writer that completely linked our conversation to the artistic universe of black female genius.

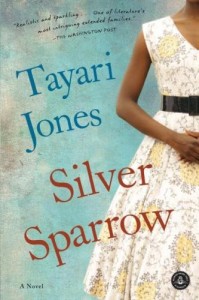

The fact that Tayari Jones comes bearing the gift of perfectly timed and aptly fitting literary allusions is just one of things you should know about her. She is the author of three novels, Leaving Atlanta, The Untelling and, most recently, Silver Sparrow. Silver Sparrow was just named among O Magazine’s 2014 “21 Books You Must Read Before the Summer Ends.”

Jones is also a teacher who teaches with ease, humor and a gently guiding hand—both inside and outside of the classroom. Most important, she is a writer who reads, like all great writers. And because she reads, she’s a writer who deeply values her own readers.

So when I sat down to interview Tayari Jones, I was most impressed by her generosity towards the women writers who mentored her and her black women readers, whom she refers to as her “base.” What Tayari reveals in our interview is that for her, and many contemporary black American writers, the base of black women readers are key to black literary success, longevity and community.

This interview is, then, a love letter to “the base.”

*******************************************

Eve Dunbar: How did you come to be a writer?

Tayari Jones: Well it’s kind of a tricky question because it’s the question of how did I come to be a professional writer. I’ve enjoyed writing all my life. I often think that I’m of the generation of black writers that can say I started writing just because I dug it. I didn’t start writing because I felt like there was a hole in my life. I enjoy reading and so I thought I would enjoy writing.

ED: How old were you when you first started writing?

TJ: A child. I used to write little books and staple them. I grew up in an all black environment, Atlanta, which is a black bourgeois mecca. Anything I could imagine someone doing, I could imagine a black person doing. I liked to write stories about children taking trips to space, you know things like that.

I never knew writing could be a serious pursuit, and I think this is where it becomes interesting to me because the challenges in my life have been more gendered than racial. When girls like to read and write people don’t think that it’s because they’re smart or they’re an intellectual. If someone says that my daughter is always in the library, people don’t say she’s a genius; they say, “Oh she probably won’t get pregnant.” Because with girls, there’s two kinds of girls. There’s “good girls” and “bad girls.” And smartness for girls is a goodness, not an intellectual kind of thing.

So I understood myself to be a nice girl and I like to read, it was like a hobby. I didn’t know that I could become a writer. It wasn’t until I went to Spelman College that I realized that I could potentially become a person of consequence and there were all these black women of consequence all around me. And it seemed like we learned to be people of consequence.

ED: So after graduating Spelman College, where did your journey to becoming a “woman of consequence” and a professional writer take you?

TJ: I went to the University of Iowa to do a PhD in literature. I did not know that you could do a degree in creative writing. I’d never heard of it. I thought that if you were a writer, you’re a writer in your soul. And so I went to Iowa and all these people were like, “We’re the writers.” And I was like, “Oh, I’m a writer too, I published a story in a magazine.” And they were like, “No, you don’t understand, we’re the Iowa writers.” And I was like, “I’m a writer, I’m in Iowa.” But they were just like, “No!”

It was good though because I learned that there was such a thing as a writer’s program and I learned that I wanted to be in one. I hated my PhD life, I hated it, it hated me. I wanted to quit but I didn’t want to disappoint my parents, my friends. And I wrote to Pearl Cleage this long letter. And she wrote me back a postcard, “You know you can quit don’t you?” And I wrote her back, “No, I did not know this.” So I quit.

ED: Where did you go after quitting your first PhD Program?

TJ: I taught adult literacy for a while and then I went to another PhD program split half creative writing half literature. Then I met a woman in an elevator, Jewell Parker Rhodes, and she said to me, “Come to Arizona, help me, I’ll get you a scholarship.” And I said, “Um ma’am no, I can’t move to Arizona. I can’t drop out of another program, it’s hot out there, they don’t have a King holiday.” And she said, “No! No! No! There has been a voter referendum, we’ll have you a King holiday by the time you get there.”

So I went to Arizona to do this MFA. I wrote my first book while I was in graduate school. And everyone was proud of me, but no one believed that I could be a writer. They thought I was setting myself up. There were no women doing anything bold and courageous.

ED: You’ve already said gender greatly influenced your writing career, it’s successes and failures, but how do you think it influences what you choose to write boldly and courageously about?

TJ: When I went to Spelman I realized the extent to which I’d been subjected fairly systematically to gender based expectations, like every woman. You know when you have that moment. And I did kind of write to explore that because that was a force that I felt overtly. So you know, I’m very interested in the way that black women try to navigate the world and I’m also interested in the intersection of class and gender.

ED: Who is your imagined audience for fiction?

TJ: My imagined audience is, interestingly, a black woman who I met through my blog. She’s a black woman with a PhD, like me, but hers is in biochemistry or something. I have to think of her because she has degree in biochemistry. Obviously she’s smarter than me, but I know something that she doesn’t know. So I’m talking to someone who’s as smart as me but may not know what I’m saying. You see, so it gives you a lot of room. There’s nothing that I can’t talk about with someone like her but I still have something to offer so I think about her

ED: Do you think of your prose as speaking to a black middle class?

TJ: I think about it talking mostly to black woman of my generation, that’s who reads my books. There’s a woman who works at the coffee cart at my job and I gave her my draft of Silver Sparrow before I finished it.

ED: Really?

TJ: She sits up all day reading. When you work at a coffee shop you read a lot. Black women read a lot. Security guards read all the time. So if there is a black female security guard who works at my publishers’ office, I always have the publishers bring her a book.

ED: I think that’s really fascinating because many people rarely think about the reading habits of working women, working black women.

TJ: Black woman are the best readers. Nikki Giovanni told me to take care of your black female readers because they will take care of you. They’ll take care of you for the rest of your career. You can fall out of favor with the New York Times whatever and whatever…. [Black female readers] will always be there for you.

When I was in between books and I was having a hard time getting my book published, black ladies were sending me stuff in the mail, cookies, knit me an Afghan. All these things helped me write the next book, so I know who loves me. A lot of people read me, but I know who loves me.

A lot of people use the word….a lot of black writers say that a book is “just” for black people. Don’t use the word “just.” I hate the word “just,” I cringe at the word. Don’t talk bad about the base. That’s the base. You make sweet love to the base, you say hello to the base.

ED: Well some people take the base for granted and constantly want to “reach out.”

TJ: I love the base. My readers are often passionate but they’re not that powerful within the industry.

ED: What do you mean?

TJ: It means that they aren’t selected to review books in high profile venues. You know their opinions… there are a lot of very famous writers who have few readers but they get a lot of visibility because their base is powerful. Ain’t nobody reading that stuff. I don’t know, I’m fairly content.

_____________________________

Eve Dunbar is an associate professor of English at Vassar College. She specializes in African American literature and cultural expression, black feminism, and theories of black diaspora. She is the author of Black Regions of the Imagination: African American Writers Between the Nation and the World (2012).

Tayari Jones is the author of three novels: Silver Sparrow (Algonquin, 2011), which was named one of the year’s best by O Magazine, Library Journal, Slate and Salon; The Untelling (Grand Central, 2006); and Leaving Atlanta (Warner Books, 2002). The recipient of fellowships from the United States Artist Foundation, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, and The Hurston/Wright Foundation, Jones is an associate professor of English at Rutgers-Newark University. Her fiction and nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times, the Believer, and New Stories From The South.

Pingback: Post 19: 40 Posts About Self-Expression | Radical Selfie

Pingback: What I’m Reading This Week | No longer unemployed, no longer a bride...