On Boko Haram, Missing Children, and Narcissism

By Niama Safia Sandy

This month I’ve watched as everyone talked about the mounting tension between the Ukraine and Russia, the Heartbleed superbug, the South Korean ferry disaster, Malaysian Airlines Flight 370, NBA team-owner Donald Sterling’s racist comments, the banana that was thrown at Dani Alves of Atletico Barcelona fame, and whatever other news items were flying around. For at least a week now, I have been following the story of the 191-234+ (reports vary on the number) kidnapped school girls in Borno State in Northeastern Nigeria on April 14.

The young girls were reportedly taken by Boko Haram, also known as Jama’atu Ahlus Sunnah Lid Da’awati Wal Jihad, an Islamic fundamentalist group founded in 2002 whose followers believe it is “‘haram,’ or forbidden, for Muslims to take part in any political or social activity associated with Western society.” Since 2011, Boko Haram has significantly ramped up its activity becoming the scourge of Nigeria and neighboring countries including Cameroon and Chad. In recent years, the group has claimed responsibility for violent incidents at mosques, churches, and other common high-traffic spaces where civilians are sure to be nearby. Thus far, according to Human Rights Watch, Boko Haram is responsible for the loss of at least 3,000 lives, at a conservative estimate.

Although the group has yet to claim any responsibility for the abductions, the girls represent the very embodiment of everything Boko Haram stands against. The Western education these young women sought (at least in theory) make them less tractable to the abuse of a man and more of a threat to Boko Haram, particularly the way of life their bombs and the strike down of ordinary citizens all over Nigeria have attempted to enforce. There are reports that the young women are being kept in the dense bush of the Sambisa Forest nature reserve where Boko Haram is purportedly based, that they are being sold and married off without their consent, or that of their parents.

Men, who are both Muslim and Christian alike, have waded through the nature reserve to find their daughters, nieces, sisters, and neighbors with no headway. The Nigerian military has supposedly also attempted its own fruitless searches. For the 18 days since these young women have been missing, few media outlets outside in Nigeria have covered the story (with the exception of The Guardian and the BBC). Is it because their lives and innocence are considered less worthwhile, less deserving of protection because they are girls? Because they are from a place that does not mean enough to the rest of the world? History has shown these are all valid assumptions.

Thus far, has even an iota of the resources offered up in search of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 been used to find the girls? That story stayed on the tongues of newscasters for at least four weeks. There were roughly the same number of souls aboard that plane as there were taken from Chibok. Is that story more mysterious and interesting than a narrative of stolen Africans – something that is frankly much more common in our collective modern history, try as we might to excise it?

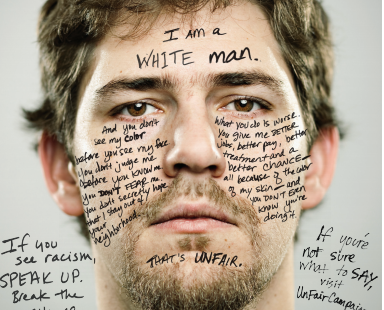

Earlier this week, I shared a post from Smithsonian Magazine’s website discussing the school girls’ story. My link has been shared 49 times (at the time I wrote this). In the time since then my social media feeds (chiefly, Instagram and Facebook) have exploded with the story; and with it has come an influx of selfies and memes featuring the #BringBackOurGirls or #BringOurGirlsBack hashtags. Although the hashtag trend began in Nigeria, I find its pervasive use in the West troubling. We have a tenden cy to play “hot potato” with topics, and by extension the people who they actually affect. I’m sure all of those who have been using the hashtag/selfie have good intentions and do so in fealty toward the families of the abducted girls and the hopes we have for the young girls and women in our own families. While that may be so, it also trivializes the matter. Sure, the use of hashtags/selfies absolutely provide a boost of agency to the affected community. But there is a certain narcissistic and callous character to a selfie; to attach one to something like this is an affront. There are lives at stake, and while the idea of literally attaching a privileged face or body to this brings these girls legitimacy in our minds, it does not negate the peril they are in.

cy to play “hot potato” with topics, and by extension the people who they actually affect. I’m sure all of those who have been using the hashtag/selfie have good intentions and do so in fealty toward the families of the abducted girls and the hopes we have for the young girls and women in our own families. While that may be so, it also trivializes the matter. Sure, the use of hashtags/selfies absolutely provide a boost of agency to the affected community. But there is a certain narcissistic and callous character to a selfie; to attach one to something like this is an affront. There are lives at stake, and while the idea of literally attaching a privileged face or body to this brings these girls legitimacy in our minds, it does not negate the peril they are in.

In New York, DC, and London, we get to hide behind our computers and iPhones and take selfies and make memes and collages that we can neatly upload to whichever social media platform we choose. There have been calls to action at Nigerian embassies and other public spaces. We believe that if we stand together donning head wraps and traditional Nigerian gelé we can implore the White House and other Western humanitarian agencies to act – how very authentically American. Unintentional but inherent condescension and cultural appropriation aside, who is all of this really for?

In New York, DC, and London, we get to hide behind our computers and iPhones and take selfies and make memes and collages that we can neatly upload to whichever social media platform we choose. There have been calls to action at Nigerian embassies and other public spaces. We believe that if we stand together donning head wraps and traditional Nigerian gelé we can implore the White House and other Western humanitarian agencies to act – how very authentically American. Unintentional but inherent condescension and cultural appropriation aside, who is all of this really for?

Boko Haram, in their disavowal of technology and Western society is not on Instagram or Twitter or online at all checking those hashtags from deep within the Sambisa forest. Boko Haram has no interest in your selfies or photo collages. One could even argue that it isn’t for the Nigerian government – as it seems they are barely interested. It’s not for the young women who are Heaven knows where. It’s not for the families in Chibok who do not know if they should be grieving for their daughters or their lost honor. The harsh truth may be that it’s for us – so we can feel better about the relative privilege, access, and safety that technology and economics afford us; about all of the knowledge and money we often squander. The fact is there is nothing that most of us – even those on the ground in Borno State – can do but pray.

__________________________________________________

Niama Safia Sandy is a Brooklyn-born Creative Anthropologist, Writer, Femi-Humanist, and Aspiring Curator of Caribbean heritage. An alumnae of Howard University and School of Oriental & African Studies (SOAS), she is a force to be reckoned with in any arena she sets foot. Her professional interests include the African Diaspora, history, gender, popular culture, and the arts.

6 Comments