By Cheryl Clarke

Editors note: Since this is a special 80th birthday anniversary forum in celebration of one of our ancestor heroines, and Cheryl Clarke was a peer and contemporary of the celebrant, TFW made the editorial decision to republish some of Clarke’s words.

Were Audre Lorde here today–and I really wish she was–she would be saying the same things she said before she left us. Her words are everlasting. Our silence still does not protect us–for long. The master’s tools will still never dismantle the master’s house–unless, like language, we use them differently. Do we still live in the “country” of “afraid”? Yes, we do, but we leave it from time to time–though we are never free of it even as we face off our deepest fears like the loss of a dearest love, a limb, a breast. Now, four years into the second decade of our 21st century, we still hear Audre Lorde’s incomparable words and warnings: “There are Lesbian and Gay writers of Color in [the U.S.] articulating in their work questions and positions which must be heard if we are to survive the 21st century,” she challenged the Publishing Triangle in 1990 upon receiving its Bill Whitehead Memorial Award. And she went on to query, “. . . . how will you define yourselves in the 21st century in a world where seven -eighths of that world’s population are people of Color? and how will you use the power that definition engenders?” Yes, how do we use our power, as 21st century black queers and black feminists writing, making art, making film, studying, teaching, feeding the hungry, feeding ourselves? We still bear the fruit and the burden of Lorde’s words.

I have written about Audre Lorde a number of times over the years since the 1980’s in various publications and venues. I would like to offer passages from some of the pieces for The Feminist Wire’s Online Forum on Audre Lorde upon what would have been her 80th year.

I must also profess my profound sorrow upon the death of (Imamu) Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones on today, January 9, 2014.

We were born in a poor time

never touching

each other’s hunger

sharing our crusts

in fear

the bread became enemy.

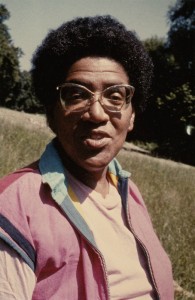

Audre Lorde knew the danger and went there anyway—toward the morning and the mourning and the moaning. Her voice gave visibility to an erotic “overtonal reverberation” of “moaning” and mourning for lost possibility.[i] She had the ability and privilege to be a visceral public presence. She used that privilege just as she used her voice to make blackness, feminism, lesbianism heard; and she used blackness, lesbianism, and feminism to make her voice heard.

What are we who advocate feminism bequeathed in the writing and life of Audre Lorde, that “strong” reader of the world, that transgressive public intellectual in this space devoted to our thoughts and feelings on the intersection of black civil rights and LGBT (lesbian-gay) civil rights? Is it perhaps urgent for us to recommit ourselves to her legacy, the study of her life, the example of her work and the use of it, before we move too much further into the 21st century? I certainly place Sister Outsider permanently on the mantle–right on up there next to Nobody Knows My Name and Home: Social Essays.[ii] But I need to take sustenance and vision from her poetry as well—which is never as transparent as her prose. As I said some years ago, the literal is not a place she remains long. She is more prone to spiral her Diaspora identities: her black Atlantic (Caribbean, U.S., and African) heritage, her Pan-Africanist consciousness, her black lesbian feminism.

The epigraph above, from Lorde’s 1984 poem “Sister, Morning is a Time for Miracles,” calls language into question as an instrument of meaning. Can we bear Lorde’s reversals–the destructiveness and the fruitfulness of language–the words that changed so much for us and at the same time bound us to their meanings/moorings? Freedom. Integration. Liberation. Equality. Power. Blackness. Relevance? Revolution? Gay? Women? Lesbian? Butch? Multiculturalism? Love? Monogamy? Social justice? Diversity? Intersectionality? Environmental justice? ‘Race ‘? Anti-heterosexist? Feminist? Black? Blackness? Cure? Anti-terror? Anti-racist? Post-modern? Same-sex marriage? Human rights? Gender outlaw? We can call out these words like we can call out the names of our dead: Joseph, David, Essex, Rose, Sylvester, Ernie, Ron, Reggie, Judy, Donald, Gloria, Maria, Ives, Marlon, Melvin, Craig . . . These words like the “bread” sometime become “enemy” or at least so commodified as to lose their efficacy. We also mourn the loss of that language, which changed our black, queer minds. Loss is a serial killer.

(From the Paper ‘Sister, Morning Is A Time For Miracles’: The ‘Morning, Mourning, and ‘Mo’nin’ in the Tutelage of Audre Lorde for the James Weldon Johnson Institute’s Working Group on the “Intersection of the Black Civil Rights Movement and the Black LGBT Civil Rights Movement,” 2011-2014)

Audre Lorde’s 1977 essay, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” is diametrically opposed to [Amiri] Baraka’s theory that “poems are bullshit unless they are teeth or trees,”[iii] and meditates on poetry as the language of women’s deepest emotion, power, and creativity. Written in 1978 in the same vein as her later essay, “The Uses of the Erotic as Power,” and appearing in the same collection, Sister Outsider, this essay reifies poetry (and women) as the source of “true knowledge” and “lasting action” (37). Baraka’s less essentialist and more hyperbolic work externalizes the potential of poetry as a force of destruction and regeneration.

Lorde sees poetry as a “dark” and “hidden” resource–much like the erotic and much like ntozake shange’s “alla my niggah blood” (for colored girls)–women carry within themselves that which will ultimately enable them to liberate themselves. Lorde never says how, for she is a visionary. Her project is to be oracular. Lorde had learned the lessons of collective struggle through her own experiences in segments of the Black Power/Black Arts Movement. . . .Lorde had witnessed and was the result of a black literary revolution to which poetry had been instrumental

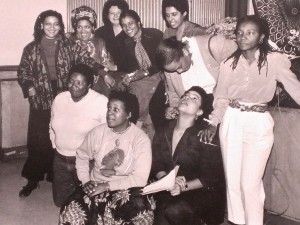

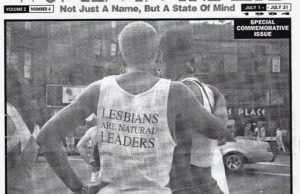

. . . . For Lorde, cultural literacy and recovery are essential to any political movement. She transferred these strategies and loyalties to progressive feminist groups, where growing multicultural communities of feminists, especially lesbians, were beginning to use the power of collective organizing to build institutions, especially cultural venues. She applied her visions to what was already happening, citing poetry as a “vital necessity of our existence,” that transforms language into “more tangible action” (37). Feminists believed Lorde’s black, lesbian, feminist vision of such indeterminacies as “more tangible action,” for we saw ourselves acting. . . . Coast to coast, North and South, black women were key organizers, theorists, revolutionists, and artists and co-existed with subtle and overt forms of sexism, male chauvinism, male dominance, and–quiet as it was kept then–heterosexism, in the black freedom struggle. But in Audre Lorde’s cosmology, black women are going to have to come to terms with their Amazon (women-loving-women and warrior) past, and learn . . . to use their power to organize “across sexualities,” as she demanded in her speech, “I Am Your Sister: Black Women Organizing Across Sexualities,”[iv] at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn.

She gave her voice to, e.g., the anti-apartheid movement, anti-violence work, most vociferously to the silence around breast cancer, and in the hundreds of places where she spoke, and her ability and privilege to be a visceral public presence. (From a Keynote for “Audre Lorde in Staten Island,” at Wagner College 2011)

Are we still listening to Audre Lorde’s “Black mother within each of us—the poet [who] whispers in our dreams: I feel, therefore I can be free.” Is she still whispering and is she still inside us. That Black Mother is still scary for me. (From the keynote, “The Passion of Blackness,” for the Feminist Fantasies Conference at the Institute for Research on Women, Rutgers University on May 12, 2012)

Writing poetry for more than 40 years and actively publishing for more than a quarter century, Lorde has presented a truly exquisite body of work (which, frankly, could bear more attention). She is a relentless exponent of the Black lesbian aesthetic. Year after year, she plumbs the interiors of her humanity as an African, a mother, a lesbian and crafts her stunning poems. The poems are ancient legacies reborn in tightly woven, startling verse and imagery, haunting us in the urban madness of Manhattan, where still can be heard ‘the voice of the sparrow’ (“A Poem for Women in Rage,”1982).

And, indeed for me, The Black Unicorn (1978), with its spare and resonating lines, its reconciliation of imageries (African, Caribbean, Afro-American), its careful grandiosity and mythic sensuousness, is her most precious inscription of Black lesbianism, a vital revision of the story of the race. . . . She continues to construct a revolutionary Black lesbian-feminist aesthetic.

Her essays have transformed the way we live our lives and do our work as feminists and lesbians. . . . Despite its tone of condescension and presumption, her admonitions in ‘Eye to Eye: Black Women, Hatred, and Anger’ (Sister Outsider, 1984) are useful to Black women as we continue to examine our internalization of racism. The poem “Between Ourselves” (The Black Unicorn), however, is a far more convincing lesson:

if we do not stop killing

the other

in ourselves

the self we hate

in others

soon we shall all lie

in the same direction

and Eshidale’s priests[v] will be very busy

they who alone can bury

all those who seek their own death

by jumping up from the ground

and landing upon their heads

(From “Knowing the Danger and Going There Anyway” for Sojourner: the Women’s Forum (Vol. 16, No. 1, 1990)

Audre Lorde’s work is a neighbor I’ve grown up with, who can always be counted on for honest talk, to rescue me when I’ve forgotten the key to my own house, to go with me to a tenants’ or town meeting, a community festival. (From a Review of A Burst of Light in Gay Community News Dec. 11-17, 1988)

Jewelle: If you look at The Color Purple, which is really a superb book, Walker doesn’t mention the word lesbian. And I don’t look at it as a negative point. . . .

Evelynn: The reason that The Color Purple raises serious questions for me about lesbians is Alice’s use of ‘womanist’ as opposed to feminist. It’s about naming. . . .

Cheryl: That’s Alice Walker. I see that as coming from a woman with a straight persona in the world. . . . I have reservations about her naming for [black lesbians]. . . . If Audre Lorde said, ‘I don’t want to call myself a lesbian anymore, I want to rename myself ‘womanist,’ I might feel differently. Audre has been out for years. She’s lived as a lesbian. She knows that history. But Alice–I love her, I think she’s fabulous–but I don’t think she should be telling me, as a black lesbian, to call myself a ‘womanist.’ (From “Black Women On Black Women Writers: Conversations and Questions,” with Cheryl Clarke, Jewelle Gomez, Evelynn Hammonds, Bonnie Johnson, Linda Powell in Conditions: Nine, 1983)

Lorde’s struggle does not culminate in her refusal to wear prosthesis, but in her struggle against the fatalistic, nostalgic, propaganda that isolates those who have cancer from their own living. ‘There is nothing wrong, per se, with the use of prostheses, if they can be chosen freely. . . after a woman has had a chance to accept her new body.’ But it is the near coercion to wear prostheses in order not to accept the challenge of a changed body that Lorde urges women to resist. Yet, how do women struggle against this repression and coercion, since many of us do not meet cancer from a ‘considered position’? How do we organize around broader goals than influencing the market to design clothes for one-breasted women? (From “A Review of The Cancer Journals“ in Conditions: Eight, 1982)

[F]or twenty-five years we lived . . . with a poet whose poetry bespeaks an inveterate traveler for whom no place or emotion is too far to go the distance. As lesbian poet and fiction writer Becky Birtha commented at an Audre Lorde memorial service in 1993 at the University of Pennsylvania: ‘The reason I am late tonight and wasn’t in my place onstage is that I cannot get used to not having Audre here. Audre was always out there–reading, meeting people, travelling . . . .’ That so many people, including many young people, across differences and generations encountered Audre Lorde personally–had not only read her work and met her, but had also talked deeply with her, shared their work with her, partied intensely with her, had been encouraged by her, driven by her–always amazes me. She was out there. (From “A House of Difference: Audre Lorde’s Legacy to Lesbian and Gay Writers,” Keynote Address to the Outwrite Conference in Boston. 1996′)’

____________________________________

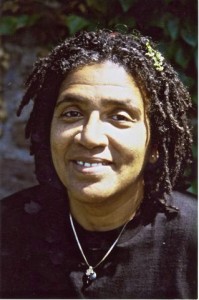

Cheryl Clarke, is the author of four books of poetry, Narratives: poems in the tradition of black women (1982), Living as a Lesbian (1986), Humid Pitch (1989), Experimental Love (1993), the critical study, After Mecca: Women Poets and the Black Arts Movement (Rutgers Press, 2005), and The Days of Good Looks: Prose and Poetry 1980-2005 (Carroll and Graf, 2006). She continues to write poetry and essays. She has written a chapbook, entitled “By My Precise Haircut.” Though she has written many essays over the years relevant to the black queer community, “Lesbianism: an act of resistance,” which first appeared in the iconic This Bridge Called My Back: Writings By Radical Women of Color (Anzaldua and Moraga, eds., 1982) and “The Failure to Transform: Homophobia in the Black Community,” which was published in the equally iconic Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (Smith, ed., 1984) continue to be favorites. She considers herself a scholar of Audre Lorde and continues to write about the impact of Lorde’s work. She recently wrote an introduction to G.R.I.T.S., An Anthology of Writing by Southern Black Lesbians (Williams, ed., Media Arts Project, 2013). Her article, “By Its Absence: Literature and Social Justice Consciousness” will appear in The Handbook of Social Justice (Reisch, ed., Routledge, 2014). She received the Kessler Award from the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at the CUNY Graduate Center in 2013. She finally retired from Rutgers University in July of 2013 after 41 years of studying, teaching, and administration on the New Brunswick campus. She is co-owner with her partner of 22 years, Barbara Balliet, of Blenheim Hill Books in Hobart, the Book Village of the Catskills.

[i] Fred Moten. “Black Mo’nin’.”

[ii] Nobody Knows My Name, James Baldwin’s second book of essays, published in 1961. Home: Social Essays is LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka’s first book of essays, published in 1966.

[iii] From Baraka’s 1969 poem, “Black Art.” in Transbluesency:The Selected Poems of Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones, 1995

[iv] See A Burst of Light, 1988.

[v] A Nigerian god, whose priests atone for those who commit suicide by jumping up from the ground and falling upon their heads, see The Black Unicorn, 1978.

You may also like...

1 Comment

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Standing at the Lordean Shoreline - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire